Body Language: Why Comics Still (and May Always) Get Women Heroes Wrong

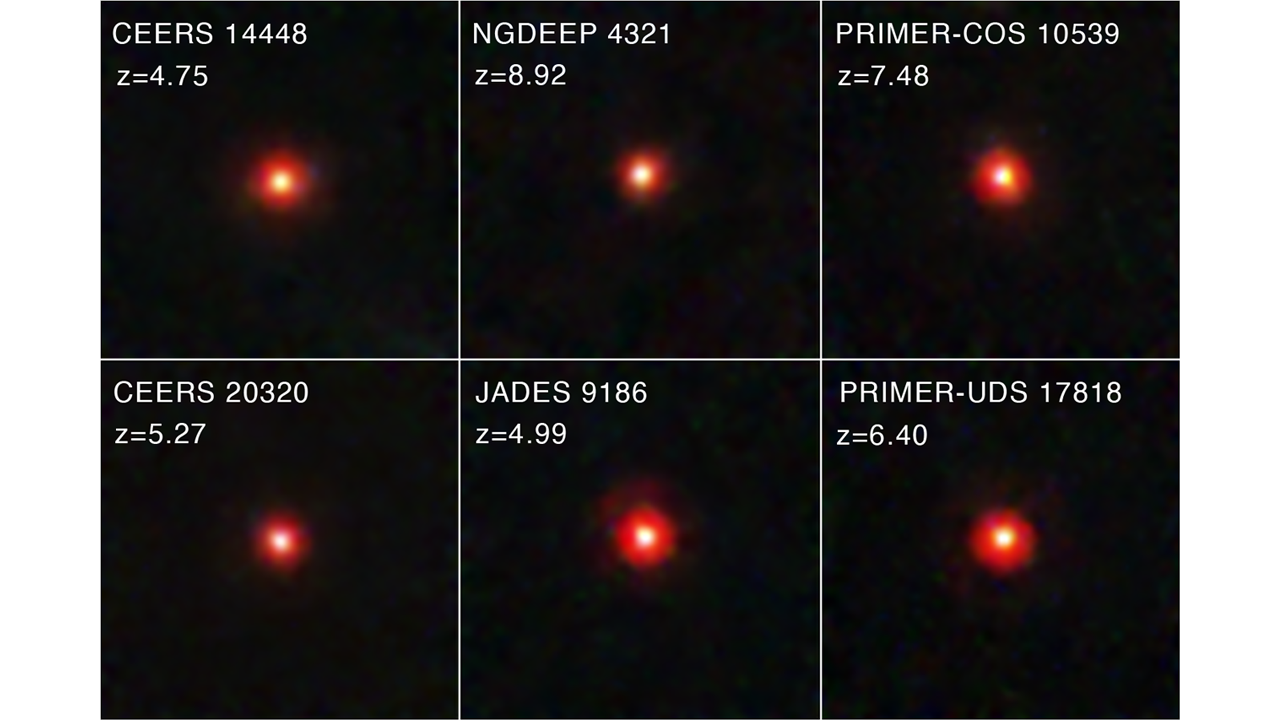

Unlike comics creators of the past, comics creators of the present can’t be faulted for not trying to make better female comic superheroes. The days of Wonder Womanacting as the secretary for the Justice Society of America are thankfully long gone — artifacts of a sexist past. Yet no matter how hard they try, comics never seem to be able to turn the genderist tide. Marvel Comics’ A-Force #1 (shown above) is a female version of the Avengers but, alas, as Harvard history professor Jill Lepore points out, “They all look like porn stars.” Why do comics still get women heroes wrong? Is it the limitations of the medium or a body language we can’t help but read and respond to?

Playboy has abandoned featuring fully nude women in its magazine which, depending on your level of skepticism, is either a positive cultural shift toward respecting the female body or a crass attempt to capitalize on it given the flood of free pornographic images online. If soft-core sells, the comic book industry can be said to have discovered the long before Playboy.

You couldn’t have lined up a more promising creative team for A-Force.G. Willow Wilson, who struck a blow for sexual equality and religious understanding in creating the 16-year-old, Muslim, shape-shifting superhero Kamala Khan for Ms. Marvel, and Marguerite Bennett, who wrote Angela: Asgard’s Assassin and improved existing female heroes and villains for Earth 2: World’s End, do the writing for A-Force. You don’t need women to write strong women characters, but having two writers so conscious of the unconscious ways female characters can be discriminated against (thus discriminating all women) can’t hurt.

Unfortunately, Jorge Molina’s art drowns out the best efforts of Wilson and Bennett. Molina’s certainly an excellent artist and draws the human body beautifully, but in many ways, he continues the same old visual stereotypes of idealized female beauty. He tries his best to keep the proportions in check, but the cleavage spills out eventually. One look at his work, especially his non-comics work he does for himself, and the words “soft porn” come to mind, echoing Lepore’s remark. Wilson and Bennett can make A-Force characters such as She-Hulk, Storm, Black Widow, Phoenix, Dazzler, Medusa, Scarlet Witch, Rogue, Wasp, Electra, Ms. Marvel, and others act and speak with power and confidence, but at the end of the day, they still look like their male counterparts with breasts (e.g., Rescue, the female version of Iron Man).

I’m picking on Molina here unfairly, since he seems a victim of sorts also trapped by the medium’s lingering problems. To me, the most egregious female hero of all time (a DC character, so she doesn’t appear in A-Force) is Power Girl. Aside from the patronizing “girl” surviving from her roots in the 1970s (unlike Marvel’s switch from Invisible Girl to Invisible Woman), Power Girl’s cavernous cleavage accentuated by the peek-a-boo window in her costume screams sexism from the past. Yet, artists continue to draw Power Girl that way, perhaps afraid to change her appearance out of fear of changing her identity and losing the audience. But it’s that very identity (and audience) that stands in the way of progress.

“Maybe it’s not possible to create reasonable female comic-book superheroes, since their origins are so tangled up with magazines for men,” Lepore points out in that same piece. “True, they’re not much more ridiculous than male superheroes. But they’re all ridiculous in the same way… Their power is their allure, which, looked at another way, is the absence of power. Even their bodies are not their own. They are without force.” Female superheroes cannot escape their sexuality, which acts as a kryptonite to both their independence and legitimacy as characters. Just as Western art history contains many more female nudes than male nudes, you can’t think of a mature female comics character who isn’t a manifestation of the male fetishizing of the female body, unless it’s for comic relief or some other narrative purpose. The default setting for female characters has always been set to “bombshell” and, sadly, may always be.

Oddly enough, this sexual component doesn’t seem to be present in male heroes. Superman, Batman, and other male figures are oddly neutered and sexless for the most part in the history of comics. Their idealized bodies are for fighting, not foreplay. Perhaps that’s a consequence of the mid-20th century views of male beauty, female sexuality, and homoeroticism in existence when these characters and the very genre of the superhero were born. When Dr. Frederic Wertham sensed even the potential for male sexuality and homoeroticism in 1950s comics, he published the infamous Seduction of the Innocent that created the repressive Comics Code, designed specifically to squash “dangerous” elements from comics while leaving behind the “healthy” ones such as cleavage and super-powered cheesecake. Whereas the Comics Code helped perpetuate comics’ visual sexism, it also resulted in damaging the male image, too, but much differently. The result of this desexualized male figure in comics is a hyper-violent caricature: What is the Hulk but an Id with no sex drive?

Just as there has been progress in comics with the introduction of male homosexual heroes, there remains hope for a better future for female superheroes. The first step, however, is challenging the physical stereotype of the female superhero body—the pneumatic porn queen of Lepore’s nightmares. Finding a way to keep the “super” without the easily read, sexually problematic body language of the superheroine body, however, will truly be a job for Superman, or Superwoman.

—

[Image: Detail from cover of A-Force #1. Image source:Wikipedia.]

[Please follow me on Twitter (@BobDPictureThis) and Facebook (Art Blog By Bob) for more art news and views.]