Between Two Worlds: The Unveiling of Yasuo Kuniyoshi

When the Whitney Museum of American Art decided to stage in 1948 their first exhibition of a living American artist, they chose someone who wasn’t even an American citizen, but only legally could become one just before his death. Painter Yasuo Kuniyoshi came to America as a teenager and immersed himself in American culture and art while rising to the top of his profession, all while facing discrimination based on his Japanese heritage. The exhibition The Artistic Journey of Yasuo Kuniyoshi, which runs through August 30, 2015, at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, DC, unveils an amazing story of an artist who lived between two worlds — East and West — while bridging them in his art that not only synthesized different traditions, but also mirrored the joys and cruelties of them.

Although Japanese museums have presented several Kuniyoshi shows since that 1948 Whitney exhibition, this SAAM exhibition is the first comprehensive show about Kuniyoshi since the Whitney’s. Of the 66 paintings and drawings selected by the SAAM curators to best represent Kuniyoshi’s diversity, many works borrowed from Japanese collections haven’t been seen in Kuniyoshi’s adopted country in over 25 years. Aside from the evolving prejudices against Kuniyoshi and his art, another reason behind this long wait is the difficulty of Kuniyoshi’s narrative — the “artistic journey” promised in the exhibition title. “Kuniyoshi’s art is subtle and sophisticated, idiosyncratic and unique,” Kuniyoshi scholar and guest curator Tom Wolf explains in the catalog. “During the course of his career it ranged from deadpan humor through erotic sensuality to deep tragedy. It is rich and profound, and should be better known.” To make Kuniyoshi better known, co-curators Wolf and Joann Moser split Kuniyoshi’s life and art into three sections: before World War II (1918-1938), during the war (1939-1945), and after the war (1946-1953). Stuck between two worlds engaged in war, Kuniyoshi found himself split as well.

Sixteen-year-old Kuniyoshi left his native Japan in 1906, first arriving in Vancouver before working his way as a fruit picker and bellhop to Los Angeles, where he enrolled in high school. His high school art teacher recognized Kuniyoshi’s potential and encouraged him to study art in New York City, where he enrolled at the Art Students League (and later taught there). In New York City, Kuniyoshi both learned painting and formed friendships with other artists (including his wife Katherine Schmidt) that completed his education as an American. Looking at archival photos of Kuniyoshi surrounded by his non-Asian friends, you get a sense of just how accepted he was by this circle of artists, yet still isolated in early 20th century America.

Kuniyoshi’s work of this early period shows him both tramping through a jungle of influences as well as unveiling his own, unique persona. Landscape (1920) represents, as Wolf writes, “a transitional piece” in which Kuniyoshi not only resolves the pleasures and challenges of Renoir and Cézanne, but does so while also merging Cezanne’s Mont Sainte-Victoire motif with the Mount Fuji motif of traditional Japanese art. Similarly, 1927’s Self-Portrait as a Golf Player pokes fun at Kuniyoshi’s avid pursuit of the popular American craze for golf (which didn’t hit Japan until after WWII), but does so by assuming a warrior’s stance and replacing the shogun’s sword with a driver. As he does throughout the catalog, Wolf wonderfully traces all the broader influences in Kuniyoshi’s art, but also hunts down specific examples, such as El Greco’s Vincenzo Anastagi portrait, which most likely served as a heroic portrait template for Kuniyoshi to start from and take in a new, interesting, idiosyncratic direction.

Adding another dimension to Kuniyoshi’s humorous self-portrait were the very real insults to him by 1920s-era America. SAAM Director Elizabeth Broun recounts how Kuniyoshi’s life “was also clouded by constant anxiety related to his immigrant status.” These tears of a multicultural clown (a frequent modern art motif he uses throughout his career) can only be seen if one is able to look closely and decode Kuniyoshi’s clues hidden in plain sight. Thanks to the “nativist racism” endemic to America at the time (and rooted philosophically in the same race theories the Nazis followed), Kuniyoshi and his wife suffered greatly. When Schmidt married Kuniyoshi in 1919, her family disowned her, refusing to even speak to her for six years. Additionally, by marrying Kuniyoshi, who, as a Japanese person, could not legally become an American citizen at the time, Schmidt, by law, lost her own American citizenship. And, yet, they bore these sacrifices with a continued faith in art and the American dream. During a trip to Japan in 1931 to see his ailing father, Kuniyoshi witnessed the growing militarism of his native country and returned to America with a new purpose.

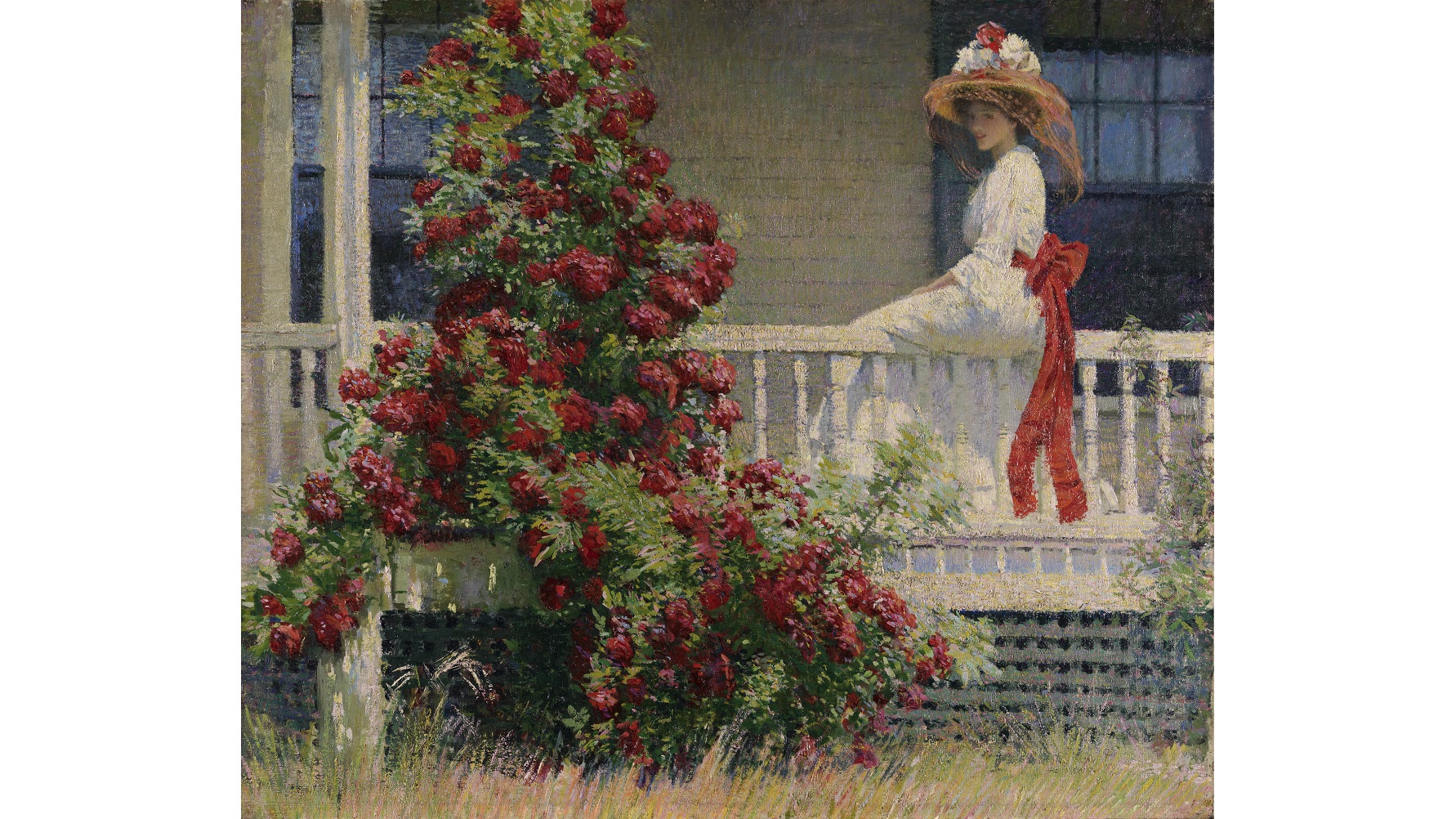

In Self-Portrait as a Photographer (from 1924; shown above), Kuniyoshi comments on his divided self. To supplement his income, Kuniyoshi photographed art for publication in magazines, etc. He shows himself emerging from beneath the cloth camera hood, revealing his (exaggerated) Asian features. There’s something Frida Kahlo-esque in this exaggeration, as if Kuniyoshi portrayed how he felt others negatively perceived his Asian ethnicity just as Kahlo emphasized her unibrow to reveal her inner anguish. Then there’s the landscape Kuniyoshi’s photographing. “Is the landscape a view out the window, or is it a painting of a landscape?” the wall text asks. “Is the landscape black and white because the photograph will be monochrome? Or do the gray landscape and barren trees suggest that he sees a bleak future?” In contrast to the standard view of Kuniyoshi as a “straightforward artist,” Wolf asserts that works such as Self-Portrait as a Photographer show Kuniyoshi’s “conceptually intricate” side.

Additional “conceptually intricate” (and Kahlo-esque) images emerge in Kuniyoshi’s women portraits of the 1930s. Wolf sees these darkly sensual, brooding women as proxies for Kuniyoshi’s own mental state. In 1935’s Daily News, the inclusion of a newspaper — full of the drumbeats of oncoming world war — subtly suggests Kuniyoshi’s growing anxieties over his ambiguous national status. Despite growing recognition as an artist, including inclusion in Paintings by 19 Living Americans (the MoMA’s second-ever exhibition), Kuniyoshi never shook critics who challenged his “American” credentials. That Kuniyoshi would slip these anxieties into a series of sensual sex objects says just as much about his powerfully creative, synthesizing imagination as it does about his fears of revealing too much too obviously.

Those fears about his alien status rose to new heights after Pearl Harbor. Living in New York City at the time, Kuniyoshi evaded the internment camps Japanese-Americans faced on the West Coast. However, the government seized Kuniyoshi’s camera, forbade him to take pictures, restricted his movements between his New York apartment and home in Woodstock, and even placed him under curfew. As if to prove his “Americanness,” Kuniyoshi began working for the Office of War Information making anti-Japanese propaganda art. In images reminiscent of Goya’s Disasters of War, Kuniyoshi depicted Japanese military atrocities of torture (including 1940s-style waterboarding) against the Chinese to argue that such Asian-on-Asian violence proved that WWII was a war of ideology, not race. In “Japan against Japan” radio speeches, Kuniyoshi continually denounced the Japanese militarism he personally separated from the larger Japanese tradition. America’s atomic bombings on Hiroshima and Nagasaki inspired Kuniyoshi to paint the 1945 hellscape of Rotting on the Shore, a powerfully pessimistic view of the aftermath of WWII in which Kuniyoshi consistently denounces the disasters of war’s human cost, regardless of the perpetrator.

After the war, Kuniyoshi continued to rise in prominence as an American artist, despite his lack of American citizenship. Just one year after the end of the war, the U.S. State Department purchased Kuniyoshi’s 1925 painting Circus Girl Resting to include in their Advancing American Art exhibition to tour overseas. Charges of obscenity and “un-American” politics against the show and Kuniyoshi (including President Harry S. Truman’s own bluntly, negative critique), however, eventually led to the cancellation of the tour. When artists from various disciplines formed the Artists Equity Association in 1947, they elected Kuniyoshi as their first president. Sadly, Kuniyoshi, the man whom the American establishment never fully accepted, became the face for the establishment in the eyes of the post-war generation of “The Irascibles” and Abstract Expressionists. Ironically, as Wolf points out, “[a]lthough he was on the other side of the generational divide from the abstract expressionists, [Kuniyoshi’s] work evolved in ways that paralleled their innovations.” Sumi ink drawings such as the disturbingly masterful Fish Head from the final years of Kuniyoshi’s life tap into the same Japanese tradition that Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Robert Motherwell, and other young guns would years later. Torn between the two worlds of East and West so long, the final two worlds Kuniyoshi found himself unfairly stretched between were the establishment past and the expressionist future.

In 1953, the final year of his life, as cancer slowly took his life while family rushed to complete the citizenship application finally made possible in 1952 by the McCarran–Walter Act, Kuniyoshi drew Old Tree. An archival photo shows Kuniyoshi cutting into the dark ink with sharp tools to produce the complex, textured look of the tree. “The tree is upright and weathered, complicated and powerful, and scarred by experience,” Wolf concludes in the catalog. “It stands for Kuniyoshi himself, a fitting finale to the artist’s rich and accomplished career.” With the 70th anniversary of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings coming next month, The Artistic Journey of Yasuo Kuniyoshi is a beautifully rich and nuanced visual rendering of the human drama of Japanese-Americans in the 20th century torn between two worlds but, like Kuniyoshi, resilient as oak, but as flexible imaginatively and spiritually as a willow.

[Image:Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Self-Portrait as a Photographer, 1924. Oil on canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Bequest of Scofield Thayer, 1982. © Estate of Yasuo Kuniyoshi/Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY.]

[Many thanks to the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, for providing me with the image above and other press materials related to the exhibition The Artistic Journey of Yasuo Kuniyoshi, which runs through August 30, 2015. Many thanks also to D Giles Ltd. for providing me with a review copy of the catalog to the show, The Artistic Journey of Yasuo Kuniyoshi by Tom Wolf, with an introduction by Elizabeth Broun.]

[Please follow me on Twitter (@BobDPictureThis) and Facebook (Art Blog By Bob) for more art news and views.]