The Dangers of Placing Too Much Faith in Yourself

Kids do the darnedest things. For instance, one time late at night, when I was 9 or 10, I opened the drawer in the kitchen, took out the biggest knife, and lightly pressed its point into my chest. I hadn’t done some homework assignment and I was thinking that maybe I would just kill myself. I suppose anyone who’d come in just then (no one did) would have been alarmed. But I was not—it’s not a particularly intense memory, and I hadn’t thought about it in years. Because as I looked down at the knife, I knew I wasn’t going to break the skin. The prospect of real violence, though close, seemed to be behind some unbreakable transparent shell; I could see all the details of catastrophe, but I couldn’t touch them. I felt as if I was watching a rehearsal for some other life, which I would not live (or leave). Lately, though, James Luria’s amazing piece in Slate (which reminded me of this long-forgotten moment) got me wondering: What if I’d had a gun?

Luria did. He was 8 or 9, and steaming mad about the immediate crappiness of his life, so he figured he’d shoot his father. Which he was about to do, with a shotgun he’d loaded, when he stopped himself.

He wasn’t a particularly weird kid. Neither was I. I’m guessing from his piece and current occupation that we were both bookish, harmless-seeming boys who grew up to be law-abiding harmless-seeming adults. We were just acting strange for a few moments. And the case for strict gun control amounts to this: When people act out-of-character, strangely and unpredictably, it is better that they not have access to a lethal weapon. Luria came close to blowing away his father, who didn’t deserve it. If I’d been playing with a pistol instead of a kitchen implement, I could have shot my head off.

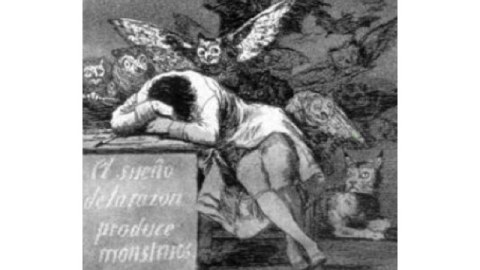

How do you argue with that? Well, for one thing you claim that strange, wild, terrible moments are mostly confined to strange, wild, terrible people (“the truth is that our society is populated by an unknown number of genuine monsters”). Once you have declared that strangeness and chaos belong only to clearly designated weirdos, you can then go on to claim that self-control and training are so well-developed in the rest of us “normal” people that guns pose no problem (“70,000,000 million gun owners obeyed the law today”). In other words, the argument for easy access to guns is an argument that most people are reliably rational—that they see their interests clearly (“I will not improve my lot if I shoot my father”) and have the self-mastery to to follow through on their insights (“so I will put this shotgun away”).

Now, obviously, most people can be pretty reasonable about guns most of the time (if that weren’t so, every town in the United States would look like the O.K. Corral). Gun deaths result from terrible departures from reason and self-control—the bullet forgotten in the chamber, the impulse to suicide made easy by a rifle, the overwhelming rage that reaches for a gun, the too-quick mis-assessment of a harmless person. It’s comforting to think that such things only happen to deeply disturbed or impaired people. But as Luria reminded me about my own life, that’s just not so. Wild, strange, terrible behavior isn’t confined to people we have marked as deranged. It’s a part of everyone’s life. We are all a great deal less reliable than we’d like to think. We are all a good deal weirder, moment by moment, than we seem. In the placid suburbs of Philadelphia, a friend of mine, when she was a 14-year-old, asked her boyfriend to copulate with his dog. And he did.

Vast amounts of psychological research have been devoted to the way people infer whole histories from a few facts about each other—both for the better (“a fine upstanding officer would never do that”) and the worse (“gay people can’t be parents!”). I’ve come to think of this kind of “social cognition” as a vast effort to reassure ourselves. I want to believe that your past performance is an indicator of your future behavior. I want to believe that your good works in one realm mean you will do good in another. I want to believe that in a crisis I will behave as I expect and hope I will. But against this desire is all the evidence that we can’t assume that the past is a guide to future behavior (see David Petraeus or, much more tragically, the case against Yoselyn Ortega). Nor can we assume that people’s well-earned social status in one context will make them immune to evil in another (see Jerry Sandusky or this video from Steubenville.

I think we’re better off when we don’t overconfidently rely on what we think we know about others, or about ourselves. When, instead, we build systems that assume that anyone can have wild, strange, even evil moments. For example, as Ezra Klein reports here, the Israeli military in 2006 stopped having soldiers take their guns home with them when they were off duty on weekends. The result was a 60 percent drop in suicides on weekends by soldiers.

I don’t deny that some people are especially deeply troubled. Far from it. But while the mass killers get the media coverage and stoke our fears, the fact is that most gun deaths result not from that kind of madness but from the far more common and ordinary kind: The kind that comes and goes in ordinary lives. And so gun control—reliance on rules and systems—seems to me a better bet than relying on the wobbly and uncertain bonds of self-control.

Follow me on Twitter: @davidberreby