Game of Thrones — the French Baby Boys’ Names Edition

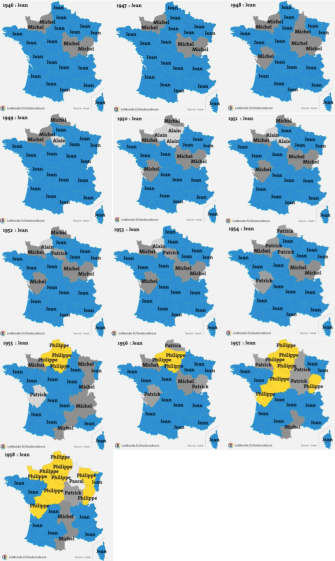

It’s 1946, and France has won the Second World War (with some help from its allies). The nation is grateful to its liberator, général de Gaulle. But that doesn’t mean mothers start naming their baby boys Charles after him. That kind of thing won’t come into fashion for some years yet. For now, the most popular boys’ name in France is Jean. As it is in most other Christian countries. As it has been, probably since the Middle Ages (1).

But by the middle of the 20th century, things start shifting. In France and elsewhere in the West, the Empire of John is coming to an end.

For the first few years after the war, all seems well — just a few local outbreaks of Michel, contained to Normandy, Burgundy/Franche-Comté and Poitou-Charentes.

But then, in 1949, the capital falls to Alain. Nobody saw that coming. The Alainists manage to break out, but are quickly destroyed, having their last stand in Basse Normandie in 1953.

By that time, however, Patrick has taken over Paris, and Nord-Pas de Calais, and other regions. Neither of these contenders will defeat Jean, though. That honour goes to yet another surprise candidate, Philippe, who in 1955 takes Paris, and three regions north of it.

By 1957, Philippe controls a band of territory from the Belgian border to the Bay of Biscayne, with an extra foothold on the Swiss border. A year later, his territory has grown yet further, and Pascal has joined the minor contenders. Jean‘s domain is cut into four shrinking bits. This is the last year of his reign.

Philippe‘s tenure will last from 1959 to 1966, but it will not be a happy one. Naturally, he will attempt to extend his dominion over the north to the south of France.

But even as he succeeds in mopping up pockets of Jean and even the last remaining stronghold of Patrick (in Provence-Alpes-Cote d’Azur, in 1961), Pascal re-emerges building a power base in the north, and by 1962 even besieging Philippe in the capital.

By now firmly in control of the south, Philippe counter-attacks, lifting the siege on Paris and re-establishing a territorial link with the isolated north by 1963.

Barely a year later, disaster strikes. Out of nothing, Thierry sweeps through the north and centre, also taking over two southern regions. Pascal is annihilated, but that is little comfort to Philippe, who loses the throne to Thierry in 1965.

His briefest of reigns only lasts a year. By 1966, a triumphant Philippe has confined him to Aquitaine, in the southwest. This will prove a pyrrhic victory for Philippe, who clings to power for just one more year.

The shape of things to come was already visible on the 1966 map: with Philippe and Thierry exhausted by their struggle for dominance (and with a withered Jean holding on for dear life), Christophe swept the north.

In 1967, he was crowned king. Taking one of Jean‘s three remaining regions, Christophe now ruled the north unopposed, except for Brittany (Philippe territory) and Paris, held by Laurent, a new pretender.

The next year, Philippe was usurped in Brittany by Stéphane, who would go on to challenge Christophe for dominance in a struggle that would last until 1974.

During all of the Christophe/Stéphane era, the former would try in vain to conquer the capital, while the latter ruled Paris for five consecutive years (1970-’74). On the other hand, Stéphane was the national overlord for only two of those eight years, against Christophe’s six.

At the close of the era, Christophe held on to the Mediterranean coast, while Stéphane controlled eastern France, with added power bases in Aquitaine and Normandy/Brittany.

Three new contenders had emerged: David in the north, Sébastien in the Centre and Poitou-Charentes, and Jérôme, holding on to the Pays de la Loire and Midi-Pyrenees regions.

Philippe had been erased from the map. Jean, the former supremo, was forced to watch the struggles on the mainland from his Taiwan-like exile on Corsica.

Now begins a time of three totalitarian rulers, each successively managing to do what even old king Jean never achieved: colouring the whole mainland in their name.

The first one was Sébastien, whose period in power began in 1975, as the top dog in a fragmented France. He soon set out to create order out of chaos, wiping various competitors off the map. In 1976, Christophe was the only mainland rival left, clinging to power in Provence-Alpes-Cote d’Azur. For two glorious years, Jean‘s Corsican exile was the only blemish on Sébastien‘s dominance.

How quickly the fortunes of onomasty change! In 1979, Nicolas carved out one single region for himself in Sébastien-dominated France. By 1980, Nicolas had swept across the mainland, leaving only Lorraine for Sébastien. The next year, Nicolas ruled over all of mainland France.

The last, and longest-ruling totalitarian broke Nicolas‘s monopoly after a single year. Julien carved out a narrow band of territory in the east, reminiscent of the ephemeral Middle Francia, created at the Treaty of Verdun (843).

This time, with reverse results: The strip gobbled up the rest of France. By 1984, Nicolas found himself isolated by Julien in Lorraine, exactly as he had kettled in Sébastien there in 1980.

The next three years, France turned entirely Julienist. Only by 1988 were there outbreaks of Nicolas, Romain and Anthony — who, in the previous year, had eliminated Jean from Corsica, thus ending the last vestiges of a name-giving tradition that may have started as long ago as the Crusades.

In 1989, a new strongman emerged on the scene, one which would dominate the next six years. Kévin would also be the last totalitarian, dominating all of mainland France in 1991 and 1992.

To get there, Kévin had to eliminate tough resistance by Maxime in Basse-Normandie; Nicolas, who attempted to set up a base in the Alsace region; Anthony, in the east; and Thomas and Jérémy in the southwest. All the while, Corsica was content to remain outside the mêlée, and loyal to Anthony, as it had been to Jean before.

Taking over Lorraine in 1993, Jordan broke the unanimity. The next year, Alexandre took over Paris, and Nicolas set up shop in the northeast, southeast, and southwest. Game over, Kévin.

In the ensuing chaos, Nicolas managed to regain the throne for a single year. But his rule proved too weak, and in 1996, Thomas began the first of his six years in power.

While he did manage to destroy an outbreak of Dylans, Thomas never managed to unify the country as previous title-holders had done. He was unable to contain a rash of Quentins, who briefly took over large swathes of western France; nor could he defeat the persistent threat posted by Lucas, operating from his power base in the east.

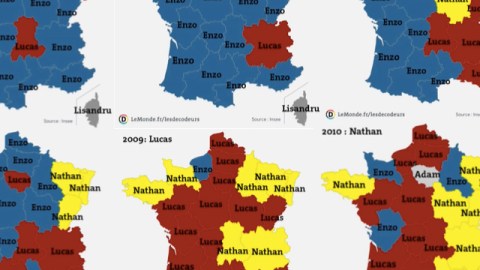

Lucas has great stamina: he came to power in 2002, and still was top dog in 2011. But he is less successful at cashing in on his dominance. His reign is punctuated by two interregnums.

Two years into his shaky first tenure, threatened by Théo, it is Enzo who almost wipes Lucas off the map in 2004.

Slowly rebuilding in the southeast, Lucas enters into a strategic alliance with Nathan, who dominates the northeast, to defeat Enzo. Lucas returns to power in 2008, but notices too late that Nathan has ideas beyond the station allotted to him.

Launching a three-pronged attack on Lucas from the northeast, southeast and northwest, Nathan grabs the throne in 2010. But his hold on power is too precarious, and Lucas still has enough stamina to regain the top spot.

That result has been achieved at great cost. In 2011, France is a house divided against itself. Nathan holds the north, northeast, the Pays de la Loire, and Languedoc-Roussillon in the south. The aim is clear: to attack towards the centre, and unite the disparate territories in a final victory. But Enzo has similarly placed possessions, and surely, similar plans.

Lucas won’t give up without a fight, and may use the newest bunch of candidates for the top job against his old enemies: Adam in Paris, Nolan in Brittany, Gabriel in Provence-Alpes-Cote d’Azur, and Lisandru in Corsica…

Many thanks to Milan Prabhu for sharing these maps on Facebook. See an animated version here. Source: Les Décodeurs, an online behind-the-news section of Le Monde, with an excellent data visualisation segment.

Strange Maps #763

Got a strange map? Let me know at strangemaps@gmail.com.

(1) The name’s enduring appeal was based on the popularity of John the Baptist and John the Apostle (considered by the Church Fathers as identical to John the Evangelist). It derives from the Hebrew Yohanan (‘graced by Yah’) or Yehohanan (‘Yahweh is gracious’). Some popular vernacular variations include Ivan (Russian and other Slavic languages); Jan, Johan(n) and Hans (German and other Germanic languages); João and Ivo (Portuguese); Jens (Danish); Juan (Spanish); Ian, Jock (Scottish); and Sean (Irish).

strangemaps@gmail.com