Two Maps of Kashmir That Make More Sense Than One

The conflict over Kashmir is decades old, frozen in time, and by now forgotten by most outsiders. Few non-subcontinentals [1] could tell you more about it than this: Kashmir [2] is disputed between India and Pakistan, who each occupy parts of it.

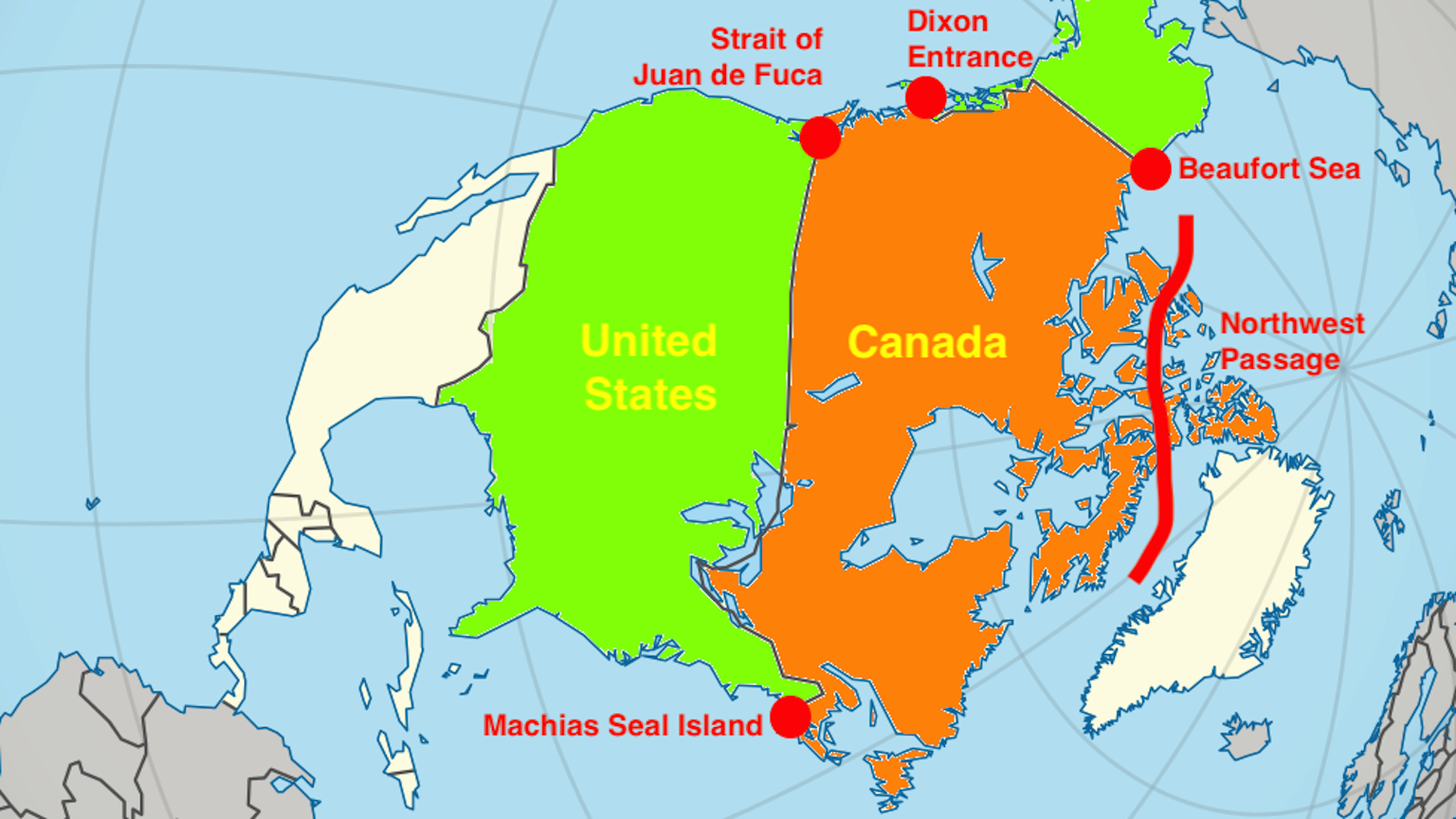

The standard map of the region isn’t very helpful either. Careful not to choose sides, it will show an overabundant mess of boundaries, complicated further by the already difficult terrain: high in the Western Himalayas, Kashmir is a maze of high-altitude peaks, interspersed with fertile valleys. And to top it all off, a third power – China – occupies part of the disputed lands, although that presence is disputed only by India, not by Pakistan.

The red line is the approximate pre-Partition border of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir. Explaining all the colours, lines and shaded areas is a bit more complex.

How did things get so messy? A thumbnail sketch of the conflict:

For British India, the joy of independence in 1947 coincided with the trauma of Partition. In theory, majority-Muslim areas became Pakistan, while regions with a Hindu majority went on to form India. But in each of the nominally independent princely states [3], the decision rested with the local maharajah. The sovereign of Kashmir, a Sikh ruling a mainly Muslim people, at first tried to go it alone, but called in Indian help to ward off Pakistani incursions.

The assistance came at a price – Kashmir acceded to India, which Pakistan refused to accept. The First Indo-Pakistani War ended in 1949 with the de facto division of Kashmir along a cease-fire line also known as the LoC (Line of Control). India has since reinforced this border with landmines and an electrified fence, with the aim of keeping out terrorists.

A Pakistani stamp from 1960 showing Jammu and Kashmir’s status as ‘not yet determined’. Note the same colour as Kashmir for Junagarh and Manavadar, Hindu-majority princely states whose Muslim ruler had opted for Pakistan, but which were forcibly incorporated into India. Pakistan hoped to use these territories as exchange material for Kashmir.

But this ‘Berlin Wall of the East’ does not cover the entire distance between the Radcliffe Line [4] and the Chinese border. The Siachen Glacier forms the last, deadliest piece of the puzzle. The 1972 agreement that ended the Third Indo-Pakistani War [5] neglected to extend demarcation of the LoC across the glacier, as it was deemed too inhospitable to be of interest. Yet in 1984, India occupied the area and Pakistan moved to counter, leading to the world’s highest ever battles, fought at 20,000 feet (6,000 m) altitude; most of the over 2,000 casualties in the low-intensity conflict, which was one of the causes of the Fourth Indo-Pakistani War (a.k.a. the Kargil War) in 1999, have died from frostbite or avalanches.

Siachen is the ultimate and most absurd consequence of the geopolitical wrangling over Kashmir. The only reason either side maintains military outposts in the area is the fact that the other side does too. The intransigent overlapping of the Indian and Pakistani claims results, among many other things, in a map, brimming with an overabundance of topographical and political markers.

Official Survey of India map, showing the entirety of Jammu and Kashmir as part of India – including the Chinese bits. Note how India now borders Afghanistan…

Could that discouragingly intricate map be a contributing factor to the obscurity of the conflict? If so, then this cartographic double-act will refocus global attention – perhaps bringing a solution closer. Which may be more crucial to world peace than you may think. Shootings across the LoC claim soldiers’ and civilians’ lives on a monthly basis. Each of those incidents could lead to a Fifth Indo-Pakistani War. Which would only be the second time two nuclear powers have engaged in direct military conflict [6]

Brilliant in its simplicity, and beautiful in its duplicity, the idea behind the two maps below is to isolate each side’s position in the Kashmir conflict on a separate canvas, instead of overlapping them on a single one. By unscrambling both points of view but still presenting them side by side on maps of similar scale and size, the divergences are clarified, yet remain comparable.

Separated into two maps, the competing claims for Kashmir [7]become a lot clearer.

Both maps show all borders as white lines, except for the crucial Line of Control that traverses the disputed area, which is shown as an black, dotted line. Third countries, notably China, are in grey, as is Afghanistan’s Wakhan Corridor [8], which provides Kabul with access to China (or vice versa), and separates Tajikistan from Pakistan.

The left hand map is the Indian version of the conflict, the right hand map shows how Pakistan sees the situation.

On the ‘Indian’ map, light yellow indicates territory under control of New Delhi, while the darker yellow and the light and dark orange bits are areas that ought to be Indian, but presently are occupied by two of its neighbours. The largest of the five dark yellow zones, named Aksai Chin, and the four smaller, unnamed ones further east along the Indo-Chinese border, are occupied by China. Pakistan formerly occupied the dark orange zone [9], which it has since handed over to China. It continues to occupy the light orange area. From an Indian standpoint, the yellow, light orange and dark orange bits together constitute the foreign-occupied areas of Kashmir.

The Pakistani map (right) has similar outlines, but different shading. The Chinese-occupied zones are grey – Pakistan does not consider these zones as occupied, but as legitimate parts of China. The area coloured light orange on the Indian map, is as green as the rest of Pakistan here: these areas are fully constituent parts of the country, divided in the Gilgit-Baltistan (formerly the Northern Territories), and Azad Kashmir (‘Free Kashmir’). The rest – the darker shade of green – is therefore occupied Kashmir.

If we were to superimpose one map on the other, the sum of all the differently-coloured zones (except those three tiny bits of Chinese-occupied territory down in the east) would make up the pre-partition state of Jammu and Kashmir. But one post-partition discrepancy remains: the disputed Siachen Glacier, which both the Indians and the Pakistani include on their side of the LoC.

So, whither Kashmir? Caught between two regional superpowers who are even prepared to kill and die over a lifeless glacier, the original vision of Kashmir’s last maharajah’s seems ever more distant: an independent, neutral, prosperous and stable Kashmir – a sort of Switzerland in the Himalayas…

Many thanks to Thibaut Grenier for alerting me to that beautiful pair of maps, found here on Le Monde diplomatique‘s weblog. Like most other great cartography at Le Monde diplo, they are the work of Philippe Rekacewicz, the magazine’s talented in-house cartographer extraordinaire. The ‘difficult’ Kashmir map found here on Wikimedia Commons. The Pakistani stamp taken from this news story on NPR. Official map of India found here at the Survey of India.

Strange Maps #629

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].

[1] ‘The Subcontinent’ is commonly understood to refer to the Indian subcontinent, the large land mass separated from the rest of Asia by the Himalayas, divided into India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bhutan and Bangladesh, but united by different strands of culture, religion, language and history (for this reason, the island nations of Sri Lanka and the Maldives are usually included in the concept).↩

[2] Not just a geographical area, also a Danish band, a Led Zeppelin song, and (although spelled as cashmere) both a type of goat and its wool.↩

[3] During the Raj (i.e. British rule over India), the subcontinent was divided in two types of territory. On the one hand, so-called ‘British India’, which was under direct British rule; and on the other hand over 550 princely states, ruled indirectly via their allegiance to the British Crown. Only 21 of these nominally independent states were sizeable enough to have their own government; Jammu and Kashmir was one of them. The princes went by a variety of titles, a common one for the grandest ones being maharaja. The British established precedence among the most important them by granting each an odd number of guns to be fired in their honour. The maharaja of Jammu and Kashmir was among 5 princes entitled to a 21-gun salute, the maximum. Those who were entitled to less than a 9-gun salute could not be referred to as ‘Highness’. In all, there were about 120 ‘salute states’. After independence, all were eventually absorbed into India and Pakistan, mostly without trouble – the most notable, lasting exception being Jammu and Kashmir.↩

[4] The arbitrated – and sometimes arbitrary – border that came into effect upon Partition. More on that subject in this article of the NYT Opinionator’s Borderlines series.↩

[5] To date, both countries fought a total of four wars; the third one, in 1971, led to the independence of Bangladesh, formerly East Pakistan.↩

[6] The first time being the Fourth Indo-Pakistani war.↩

[7] Cachemire, the French name for the area, has an even more exotic ring to it than ‘plain old’ Kashmir; on the other hand, it sounds a lot like cauchemar – ‘nightmare’.↩

[8] More on Wakhan in thisBorderlines story.↩

[9] The Shaksgam Valley, a.k.a. the Trans-Karakoram Tract.↩