110 – Cooch Behar: The Mother of All Enclave Complexes

n

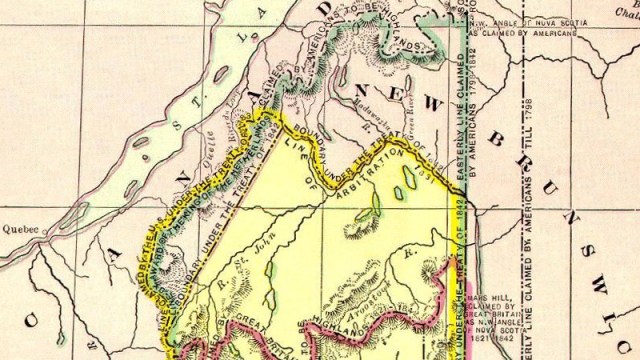

A map that does justice to the strangeness of the Cooch Behar enclave complex risks either to be too big to conveniently post here, or too small to show the intricacies of enclaves and counter-enclaves on both side of the Indian-Bangladeshi border. But the story behind this, the world’s largest enclave complex, is so compelling that I’ll write it up first, and wonder about the map later.

n

Firstly, though this enclave complex is conventionally named ‘Cooch Behar’, that is only telling half of the story. The complex exists on both sides of the northern part of the Indian-Bangladeshi border, but is named only after the Indian half of the area.

n

- n

- Cooch Behar, formerly an independent principality on the Indian subcontinent and now a district in the Indian state of West Bengal, possesses 106 exclaves in Bangladesh, totaling 69,6 km². Of those, 3 are counter-enclaves and 1 a counter-counter-enclave. The biggest Indian enclave is Balapara Khagrabari (25,95 km²), the smallest Panisala (1.093 m²).

- Conversely, Bangladesh possesses 92 exclaves inside India, comprising 49,7 km². Of these, 21 are counter-enclaves. The largest Bangladeshi exclave is Dahagram-Angarpota (18,7 km²), the smallest is the counter-enclave Upan Chowki Bhaini (53 m²), the smallest international enclave in the world.

n

n

n

Rough estimates for the total population of all enclaves together ranged up to 70.000 at the beginning of the 21st century.

n

For the origins of most enclaves, we have to go back to 1713, when a treaty between the Mughal Empire and the Cooch Behar Kingdom reduced the latter’s territory by one third. The Mughals didn’t manage to dislodge all Cooch Behar chieftains from the territory thus gained; at the same time, some Mughal soldiers retained lands within Cooch Behar proper while remaining loyal to the Mughal Empire. This territorial ‘splintering’ was not so remarkable in the context of that time: the subcontinent was extremely fragmented (comparisons with pre-1871 Germany spring to mind), most enclaves were economically self-sufficient and the fragmentation caused no significant border issues, as Cooch Behar was nominally tributary to the Mughals anyway.

n

- n

- In 1765, the British seized control of the Mughal territory by way of the East India Company, which in 1814 was surprised to discover extraterritorial dots of Cooch Behar within its territory, “by some unaccountable accident”. Those enclaves were sometimes used as sanctuary by “public offenders” fleeing the police.

- In 1947, the formerly Mughal territories became part of the eastern part of Pakistan.

- Cooch Behar acceded to India only in 1949, as one of the last of the 600-odd pre-independence Princely States to do so.

- In 1971, East Pakistan gained independence as Bangladesh.

n

n

n

n

n

Remarkably, the enclave complex survived all these changes of sovereignty on both sides of the border – although the enclave complex used to be even more complex before India’s independence: 50-something Cooch Behar exclaves in Assam and West Bengal were rationalized away after all three entities became parts of India.

n

Attempts in 1958 and 1974 to exchange enclaves across the international border proved more elusive – even though the international aspect of these enclaves made administering them extremely unworkable, and thus such an exchange more useful than that of the aforementioned all-Indian enclaves. For the border situation has often made it impossible for people living in the enclaves to legally go to school, to hospital or to market. Complicated agreements for policing and supplying the enclaves had to be drawn up (a 1950 list of products that could be imported into the enclaves contained such items as matches, cloth and mustard oil).

n

In a classic example of a vicious circle, residents of enclaves need visa to cross the other country’s territory towards the ‘mainland’, but since there aren’t any consulates in the enclaves, they should go to one in the ‘mainland’ – which they can’t because they don’t have a visum. Illegal border crossings are frequent, but dangerous – a number of transgressors have been shot by border guards. Furthermore, the enclaves remain a haven for criminals who are thus immune from the justice system of the country surrounding the enclave – exactly as it was back in 1814. These and other problems have rendered the enclaves pockets of lawlessness and poverty compared to their already relatively poor motherlands.

n

Since the issues of sovereignty, territorial integrity and especially the unwillingness to let the other side seem to ‘win’ is so sensitive for both India and Bangladesh, the Cooch Behar enclave complex probably isn’t going to disappear anytime soon. There is one example of progress, however: the Tin Bigha corridor, connecting a Bangladeshi enclave with its ‘mainland’ – although it took twenty years to happen, met heavy opposition and cost people’s lives.

n

Meanwhile, I’ve found a map that looks nice – and strange – enough to post here, although it suffers from the first defect aforementioned (too big). It shows, roughly, three enclave hotspots:

n

- n

- First, and westernmost: an (mainly Indian) archipelago of enclaves, the Indian ones surrounded by the Bangladeshi administrative areas of Pochagar, Boda, Debiganj and Bomar. There are a few Bangladeshi dots in the Indian area of Jaipalguri. And at least three pink (Indian) dots apparently on the Indian side of the border – I’m not sure what that means.

- Secondly, and centrally: a mixed Indo-Bangladeshi archipelago, consisting of a number of Indian enclaves inside the administrative area of Patgram – which itself is a Bangladeshi protrusion into Cooch Behar (but contiguous with Bangladesh proper). To the east, north and west of Patgram, and therefore within India, are a number of Bangladeshi enclaves.

- Lastly, to the east: again a mixed archipelago, but more spread out than the previous two, with Indian exclaves inside the Bangladeshi districts of Lalmanirhat, Phulbari, Kurigram and Bhurunghamari and Bangladeshi exclaves inside the Indian districts of Dinhata, Cooch Behar proper and Tufanganj.

n

n

n

n

The map, found here on Jan Krogh’s very interesting GeoSite, shows many enclaves-within-enclaves (see post #60 on this blog on Madha and Nahwa for a clearer map of what that looks like) and indicates one enclave-within-enclave-within-enclave (#51 on the map, quite possibly the only one such counter-counter-enclave in the world). The map has several drawbacks: it doesn’t show a scale, making it difficult to size up the area depicted; there are no names next to the numbered enclaves; and those numbers only go up to 129, as far as I can see. That’s 69 enclaves less than the total mentioned above (106 Indian + 92 Bangladeshi = 198 enclaves).

n

That total, and most of the text for this post, is based on the relevant passage of Evgeny Yuryevich Vinokurov‘s ‘Theory of Enclaves’ (2005, 272 p.). Vinokurov is a Russian postdoctoral researcher at the Institute for World Economy and International Relations at the Russian Academy of Sciences. He’s apparently based in Kaliningrad and (hence) interested in enclaves and exclaves.

n

Vinokurov’s bit about Cooch Behar is based on ‘Waiting for the Esquimo’ (2002, 519 p.), an exhaustive case study of the Cooch Behar enclave complex by Brendan Whyte, an Australian political geographer based at the University of Melbourne.

n

Finally, in this text I’ve used the words enclave and exclave interchangeably, which I think is allowed: one country’s enclave (foreign territory within one’s own) quite literally is another country’s exclave (own territory surrounded by another country’s).

n