Scientists Discover The “Master Controller” Neuron of Good and Bad Habits

Scientists at Duke University have identified a neuron that acts as the “master controller” of habits. The findings, published in the journal eLife, could someday change the ways addiction and compulsive behavior are treated.

The “master controller” of habit appears to be a rare cell called the fast-spiking interneuron (FSI), which shows boosted activity during habit formation and, interestingly, seems to shut down habit behaviors when suppressed by drugs.

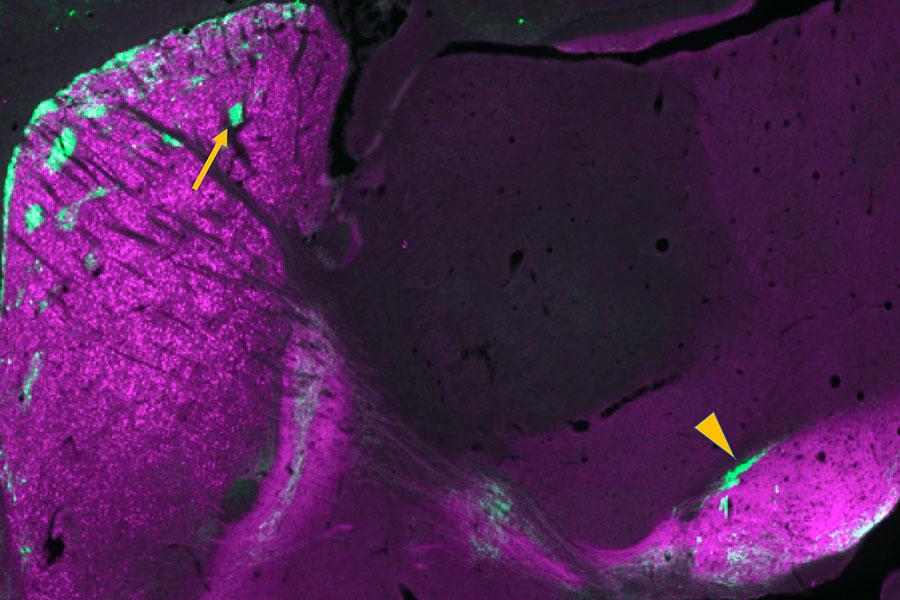

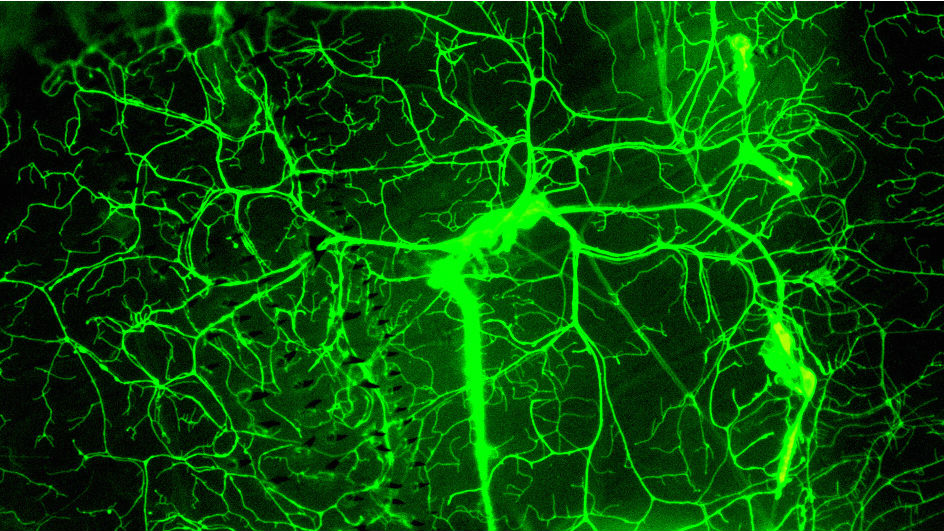

FSIs, which belong to a class of neuron that relays messages between other neurons, are found in a region deep within the brain called the striatum. Here, FSIs make up only 1 percent of cells, but they have long branch-like tendrils that allow them to connect with 95 percent of the other neurons associated with habitual behavior.

“This cell is a relatively rare cell but one that is very heavily connected to the main neurons that relay the outgoing message for this brain region,” said Nicole Calakos, an associate professor of neurology and neurobiology at the Duke University Medical Center, to Duke News. “We find that this cell is a master controller of habitual behavior, and it appears to do this by re-orchestrating the message sent by the outgoing neurons.”

It’s been known that habit formation can effectively rewire the brain, but exactly which neurons cause and control this process has been unclear. The team behind the new study wanted to change that.

“We were trying to put these pieces of the puzzle into a mechanism,” Calakos said.

In 2016, the Duke University researchers published their first insights into habit and its effects on the brain. They found that habit formation in mice resulted in long-lasting changes in the striatum, which has two sets of neural pathways: a “go” pathway that triggers action, and a “stop” pathway that inhibits it.

The results showed habit formation made both of these pathways stronger, and also caused the “go” pathway to fire before the “stop” pathway.

A magnified view of the striatum of a mouse brain, fast-spiking interneuron in purple. Credit: Justin O’Hare, Duke University

Still, they weren’t quite sure which neurons were effectively running the show in the striatum. To find out, the researchers, led by graduate student Justin O’Hare, first observed that FSIs become more excitable when a habit is formed. Then they administered a drug to habituated mice that suppresses the firing of FSIs. The results? The “stop” and “go” pathways in the striatum reverted to “pre-habit” patterns, and their habit behaviors vanished.