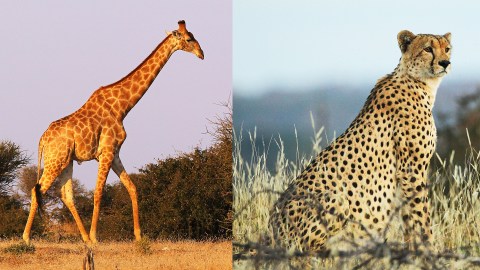

Giraffes and Cheetahs Are Going Extinct, Warn Scientists. Why Should Humans Save Them?

Experts are warning that two iconic animals are nearing extinction.

Giraffes, world’s tallest animals, suffered a grave decline in their population, losing 40% of it in the last 30 years. There are about 97,500 giraffes in the world today, plummeting from 157,000.

Giraffes were added to the so-called “red list” of threatened species, compiled by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). They were given a ‘vulnerable’ status.

Cheetahs, world’s fastest land animals, are faring even worse. There are about 7,100 of them remaining in the wild, with their numbers decimated in places like Zimbabwe by 85%, according to a new study from the Zoological Society of London (ZSL) and Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS). Calls are out to change its status on the “red list” from “vulnerable” to “endangered”.

“We’ve just hit the reset button in our understanding of how close cheetahs are to extinction,” said Dr. Kim Young-Overton, from Panthera, a wild cat conservation organization. “The takeaway from this pinnacle study is that securing protected areas alone is not enough. We must think bigger, conserving across the mosaic of protected and unprotected landscapes that these far-reaching cats inhabit, If we are to avert the otherwise certain loss of the cheetah forever.”

Animals go extinct for a variety of reasons, most of them having to do with human interference in their habitats. In fact, it’s considered the animal kingdom is undergoing a “mass extinction”. An analysis of wild creatures found that their number will be reduced by two-thirds come 2020, if compared to 1970.

The list currently features 24,000 species at risk of extinction. Notably, the “red list” recently added 700 new bird species to its listing, 13 of which already went extinct.

“Many species are slipping away before we can even describe them,” said Inger Andersen, the director general of IUCN. “This red list update shows that the scale of the global extinction crisis may be even greater than we thought. Governments gathered at the UN biodiversity summit have the immense responsibility to step up their efforts to protect our planet’s biodiversity – not just for its own sake but for human imperatives such as food security and sustainable development.”

Of course, as with all things, there are naysayers, who view protecting endangered species as a waste of money that goes against survival of the fittest – a natural process. A 2012 study estimated it would cost $76 billion per year to preserve land animals under threat. And then there are similar costs for the marine animals. Why should we spend so much money and who should be spending it? What about helping people instead?

There’s also something to be said – why should we care specifically about giraffes and cheetahs? Why are they more special than, let’s say, chicken? Of course, giraffes and cheetahs are more rare, but consider how many chicken are slaughtered every year – about 8-9 billion in the U.S. alone. Worldwide, this number, while probably hard to exactly estimate, is north of 50 billion.

A chicken peers out from a cage at the Sanoh chicken farm January 27, 2007 in Suphanburi, Thailand. (Photo by Paula Bronstein/Getty Images)

Why do we not seem to care for the yearly extermination of a mind-boggling number of chicken? Ok, sure, they seem to be replaceable, but life is life. We value the esthetics of giraffes and cheetahs, beautiful and graceful animals, and thus exercise our choice to try to save them. What if we thought about humans that way? Only saving the pretty ones.

Against all this is, of course, the argument that biodiversity is key to preserving a healthy ecosystem, which we, humans, rely on for our own survival. Studies by ecologist Robert Constanza estimated that the benefits of conservation also have a significant economic impact. They outweighs the costs by a factor of 100.

And certainly humans are the ones increasing the rate of extinction. It is not proceeding at a rate observed in the past. You can argue that humans are also part of nature and as such everything we do is a natural process. But that seems like a way to absolve ourselves of any free will and responsibility.

The Endangered Species Act of 1973, an achievement of President Richard Nixon’s administration, provides a great summary argument for why saving endangered species is important, saying they “are of esthetic, ecological, educational, historical, recreational, and scientific value to the Nation and its people.”

Still, at the end of the day, should we save giraffes and cheetahs? The answer depends on how you view the world. Let’s hope no one has to make such decisions about the human race some time down the line – like our future AI or alien overlords.

Cover photos: Mashatu game reserve. Botswana. Credit: Cameron Spencer/Getty Images.