Myself as a Commonwealth: Notes on the Science of Self

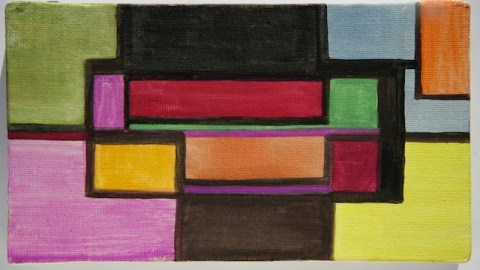

We imagine our view of the world like a painting from the Realism movement – rife with detail and comprehensible – but the contents of our conscious mind are more like a work of Pop Art, full of abstractions and open to interpretation. The problem, as any MOMA goer will confess, is that it’s difficult to interpret a world full of ambiguity. You can spend a career studying Rothko or Pollock and reach a different conclusion from the modern art professor down the hall. Worse, as any art historian will admit, even the artist struggles to explain his preferences.

Many times trying to explain those preferences actually makes you worse off. Consider a 2003 experiment conducted by an all-star team of psychologists including Jonathan Schooler, Dan Ariely and George Loewenstein. Participants listened to Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring and either evaluated their state of happiness while listening to the composition or after it finished. The three psychologists discovered that the participants who continually monitored their experience reported lower levels of happiness compared to their peers in the other group. In other words, by trying to understand why something is pleasurable, we might destroy the pleasure.

The focusing illusion is a related phenomenon that demonstrates how directing our attention towards one bit of information distorts our thinking. In a revealing study a researcher asked college students two questions: “How happy are you with your life in general?” and “How many dates did you have last month?” The ordering of these questions mattered. Researchers did not find a correlation in the group that heard the question about life satisfaction first. But when they asked the questions the other way around the students implicitly evaluated their life in terms of how many dates they had been on. As a result, students with many dates reported higher levels of happiness than students with fewer dates.

What does this research tell us about the mind? It’s uniquely human that we can reflect on our beliefs and preferences. Yet, psychological science demonstrates that when and how we do this actually alters those beliefs and preferences. This is not obvious.We like to think that who we are – what we enjoy, who we like, and how we decide – is immutable and that introspection provides a transparent window into the self. The problem with this perspective is where my analogy comparing the self to Pop Art breaks down. It’s true that it’s often difficult to interpret the contents of our mind, but unlike No. 5 or Ochre and Red on Red, the self is an illusion. It’s not just that you are full of abstractions; there’s no unified “you” to begin with. MOMA goers will interpret No. 5 and Ochre and Red on Red differently, but at least they’re looking at the same paintings each time.

**

Let’s explore this a bit further. In the early 20th century William James famously separated “I” from “Me.” The “I” describes our conscious experiences from one moment to the next. You might think of it as the CEO of the mind. “Me” is a collection of our past experiences, current activities and future aspirations; it is the low-level employees who document changes, make projections and occasionally report to the CEO. James’ distinction was an important one for modern psychology because it recognized our fragmented mental life. Today we can do a bit better.

Starting in the late 1970s psychologists began demonstrating that people do not realize the reasons for their feelings and decisions. Timothy Wilson and Richard Nisbett famously showed that women described nylon stocking uniquely (i.e., texture, softness) in a field study under the guise of a customer evaluation survey even though unbeknownst to the women the pairs were identical. Similarly, a different group of scientists gave participants three different colored boxes of detergent to trial for a few weeks. The participants overwhelmingly favored the detergent with a colorful box and their reasons elaborated on the merits of detergents even though the content of each box was, in fact, identical. Years later a group of researchers headed by Adrian North discovered that when an English supermarket played French music 77 percent of the wine purchased was French, while the days it played Germany music 73 percent of the wine purchased was German. Importantly, only one of the 44 customers polled reported that the music influenced their decision. A popular response to this research is to denounce human rationality or conclude that we are at the mercy of subliminal effects. Another is that the “I” James wrote about is an ever-evolving narrative fueled by after the fact rationalizations. The “Me,” if there is such a thing, is simply inaccessible.

Here’s where things get meta. Philosophers and many 20th century psychologists used to think that the question “what is the nature of the self?” was difficult because the self was so complex. Now the more challenging question is, “which self are you talking about?” David Hume famously compared the self to a “commonwealth, in which the several members are united by the reciprocal ties of government and subordination.” Close. Modern neuroscience and psychology suggest that it’s more like dozens of members, and they are not necessarily united – we might imagine a UN assembly. This idea explains many oddities of the human condition: why we smoke, procrastinate, cheat, and eat poorly knowing the long-term negative consequences. A unified theory of the self could never account for these contradictions.

And it’s not like each of these “sub selves” are immutable either. Sometimes your cheese and fat craving self beats your health-conscious self. Studies show that certain primes influence our moral judgments; depending on the prime, either your angel or devil will do the judging. Research conducted by Dan Ariely found, not surprisingly, that when we are sexually aroused our willingness to engage in some sexual acts increases significantly. Stranger still, we’re acutely aware that one self might dominate another self in certain circumstances. This is why instead of going to the bar for “just one beer” we simply don’t show up.

This brings me to the relationship between the self and the circumstance. Tufts Professor of Psychology Sam Sommers writes about how context shapes behavior. While not diminishing the role of genetics, Sommers outlines the many ways situations determine our behavior. For instance, it’s easy to punch in credit card information and donate 10 dollars to a good cause, yet if you stroll the streets of Manhattan you’ll notice those same givers walking past homeless people begging for change with indifference. Altruism, it seems, depends on the circumstances. Where does this leave us?

If the self is an illusion generated by flimsy narratives and competing brain modules, then who is doing the narrating? In his book The Self Illusion the psychologist Bruce Hood notes that the philosopher Gilbert Ryle observed that with respect to the mind you cannot be both the hunter and the hunted. Hood’s counter intuitive point is that you cannot separate a thought from our awareness of that thought. As he puts it, “the brain creates both the mind and the experience of mind.”

**

Last year Dan Gilbert and two researchers published a paper in Science that outlined what they termed the “end of history illusion.” They note that we know that our past self seems quite different from our present self. Tastes change, relationships come and go, and we remember that who we were ten years ago is different from who we are now. If that sounds obvious consider that when the researchers asked participants (nearly 19,000 of them) to make projections about their selves in ten years most reported that they would stay the same. “People,” the researchers conclude, “regard the present as a watershed moment at which they have finally become the person they will be for the rest of their lives.”

At least two reasons explain this finding. First, we generally believe that our personalities are attractive and our values and preferences are admirable. Given these lofty traits, we might be reluctant to foresee change because it will only be for the worse. Second, making projections about the future is hard. It’s easy to look back and read the story of your life. However, it’s nearly impossible to accurately predict who you will become, so you simply go with the default option – yourself in the present. The takeaway isn’t that we change over time – that’s obvious – but given the nature of memory and biases the present will always distort how we think of the past and the future.

I imagine the end of history illusion to resemble the perspective from the bow of a motorboat. Looking back we notice the churned up water and conclude rather obviously that we are moving away from it. When we look forward we see the opposite: calmness. Yet for some reason we conclude that it will stay that way, as if the boat will stop carving out a wake.

Again, my analogy is not perfect. If there is one conclusion from the science of the self it is that the singular nature of term “the self” is misleading. There is no one perspective looking forwards or backwards, nor is there one painting to interpret. I think Hume said it best when he compared the self to a commonwealth – sometimes productive and coherent and other times not. Somehow, though, an identity emerges from the collective. The singularity and unity is an illusion. But as Dan Dennett points out, it’s a convenient and cohesive one.

Image via Shuttershock/Robert Buchanan Taylor