Valley of the Dolls: Women’s Wage Woes in the Tech “Shangri-la” of Silicon Valley

In a fascinating report—a Tale of Five Californias—the non-profit Measure of America describes the state’s distinct economic communities. From “The Forsaken Five Percent,” who have been “bypassed by the digital economy and left behind in impoverished LA neighborhoods,” to “Main Street California,” the better-educated “suburban and ex-urban Californians” with a “tenuous grip on middle-class life,” and to “Shangri-la”—prosperous Silicon Valley.

Shangri-la residents, 1 percent of California’s population, are also the “top 1% of the population in well-being.” Shangri-la is an enclave of “extremely well-educated, high-tech, high-flying entrepreneurs and professionals fueling, and accruing the benefits of, innovation, especially in information technology,” the report says. “Highly-developed capabilities give these Californians unmatched freedom to pursue goals that matter to them.”

That sounds like the usual hyperventilation about innovation and “high tech,” a world where you shake a tree and VC dollars flutter into your visionary, entrepreneurial hands.

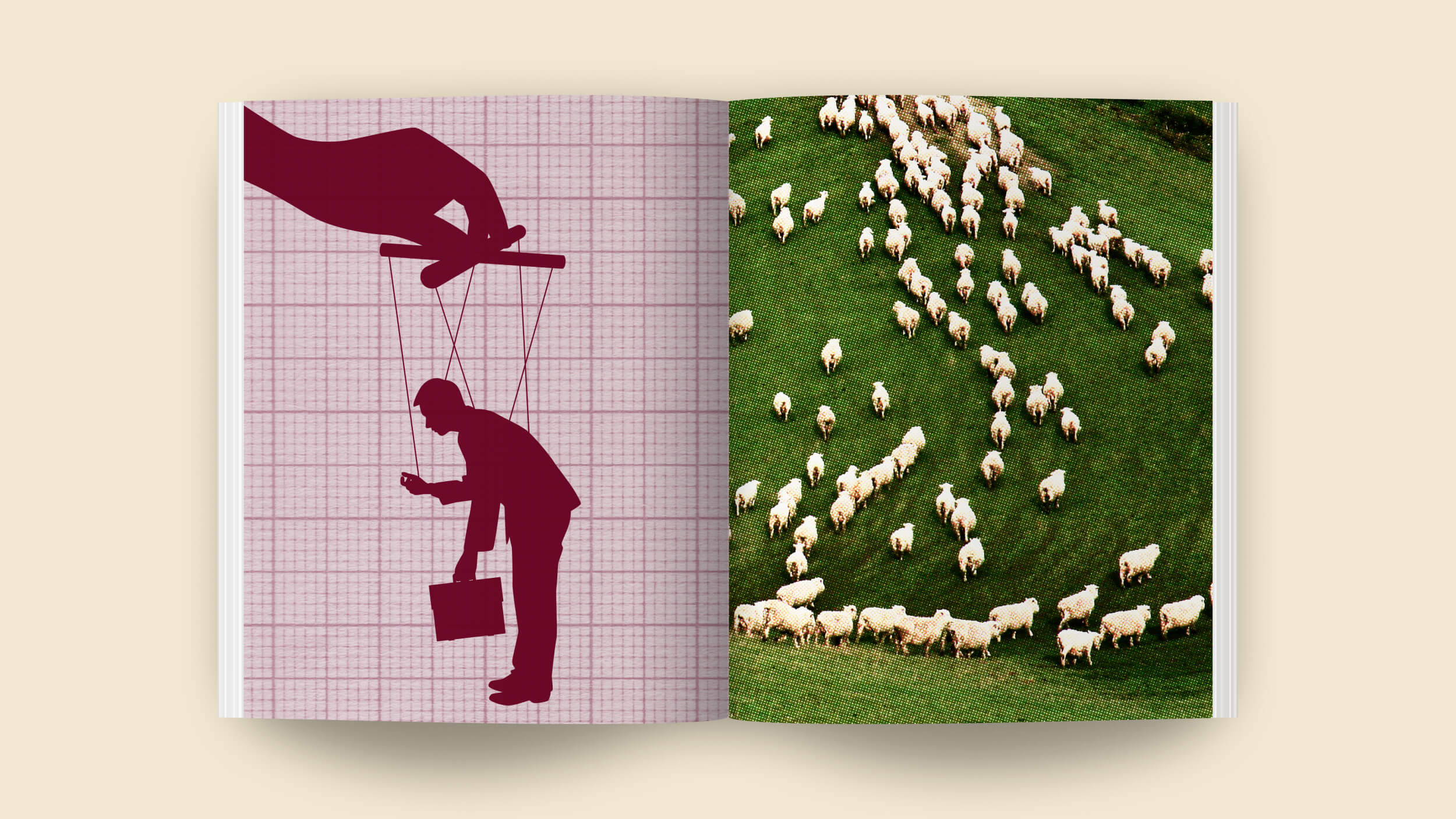

But Measure of America discovered a worm in the tech utopia. Silicon Valley’s wage gap and income inequality between men and women must surely rank among the worst in the country.

Women in Silicon Valley earn only 49 cents to a man’s dollar.

That’s far worse than the national wage gap, estimated at 78 cents to a dollar. In fact, Silicon Valley’s income inequality is dramatically worse than the wage gap nationally in 1967, and even in 1950, when women earned 58 cents to a man’s dollar, and newspapers ran sex-segregated job listings that said, “Help Wanted—Male” and “Help Wanted—Female.” Some would publish different pay scales, for the exact same jobs, in the adjacent “male” and “female” columns of the same classified section.

To find female-to-male median earnings for full-time, year-round workers in the U.S. that’s comparable to Silicon Valley in 2012, you’d have to go back to the year 1905, when Theodore Roosevelt was president, plastic had just been invented, Einstein first proposed the theory of relativity, and the newfangled high tech of radio was still under development. Silicon Valley’s wage gap isn’t much better than that of 1890, either, the earliest data that I could find, when women earned 45 cents on the dollar.

The most cutting-edge place in our economy has the most retro wage gap.

My hunch is that this paradox is an artifact of occupational segregation. Silicon Valley has a specialized economy. A preponderance of its well-compensated occupations are high-tech and tech-entrepreneurial—fields that are still dominated by men. The dearth of women in these high-income professions, in contrast to their parity in most other white-collar fields such as law and medicine, would skew the overall income gap.

Sarah Burd-Sharps, one of the report’s authors, explains in an email that they found this to be the case: “Silicon Valley is home to an exceptional concentration of people with very high earnings,” she says. “And most of them are men…. Three-quarters of those earning over $125,000 a year are men, many working in management, computer programming, and research occupations. Conversely, of those who earn under $25,000 per year in Silicon Valley, two-thirds are women.”

More economically diversified communities in California, with a more balanced representation of well-paying, sex-integrated white-collar professions, see a smaller gender gap. Ironically, although California’s “Forsaken” are far worse off, male and female workers there are far more equal than Shangri-la in their wages (or plight), with a wage gap that mirrors the national one.

The Center for American Progress reports that nationwide, 40 percent of the wage gap is simply “unexplained” by factors such as job choice or work experience. Others estimate that about 25 percent of the wage gap is explicable by occupational choice. I wonder if a higher percentage of the wage gap in Silicon Valley, specifically, is explained by occupational segregation.

Hopefully, if we did in-group comparisons, we’d find that women who dohold high-tech, prestigious, innovation positions in the Valley economy are earning comparable to their male colleagues, or at least “enjoying” a wage deficit that’s closer to the average. Burd-Sharps finds that this is so. “Of all workers in computer and mathematical occupations in Santa Clara County which have overall median earnings of about $100,000,” she says, “women make up under one quarter of the workforce in these occupations, and their median earnings are only about 84 percent of men’s in the same jobs.” While 84 cents on the dollar is bad, it’s not as bad as 49.

It’s hard to dismiss the Valley just as an economic idiosyncrasy.

Indeed, “Silicon Valley” is at this point both a place and a synecdoche for an entire economy—the (high-tech) economy that shows promise for future growth, and whose innovations are reshaping almost every aspect of our culture, from media to medicine. Such a dramatic wage gap could be a canary in the coal mine, a warning about income and “influence” inequality to come as one of the most important sectors of the 21st-century economy expands its reach.

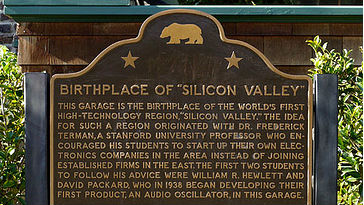

Just as women have dramatically closed the gap on prestigious professions such as law and medicine, it seems that the action has moved elsewhere. I joke in my book (Now Available in Paperback) that while women were dutifully completing their advanced professional degrees and years of schooling, their male classmates had dropped out, set up shop in their parents’ garage, founded a tech start up and retired at 40.

It’s worrisome if this wage gap indirectly reflects occupational re-segregation by sex, and women’s limited presence and influence in the innovation crucible of Silicon Valley.

There are no easy explanations, or remedies, for women’s under-representation in the field. Burd-Sharps and her colleagues point to the lack of family-friendly work policies, which are certainly important.

Courses of study and job choices are important, too. Women can’t be forced to pursue things they don’t want to pursue. Still, it can’t possibly be the case that women are implacably and inherently less interested in the digital economy by 51 cents on the dollar.

As a start, how do we encourage girls and young women to see themselves as inventors and visionaries in the field, rather than just as end-users or consumers of information technology? Children should be thinking about how to make the technology, not simply to use it.