Subjectify Me: The Unfinished, Backsliding Consent Project

What’s the most perfect, ideal, pure act of sexual consent that you can imagine?

Maybe it would be you and your most favorite lover, ever, in a hotel room for the afternoon: “You and me! Right here! Let’s have sex!” you both say—at the same time, out loud, in the same language, soberly, sincerely, and with obvious relish.

At the other end would be the gang rape, beating, and murder of an Indian woman, on a bus, or rape used as a systematic tool of war and social destruction in Congo, or Syria.

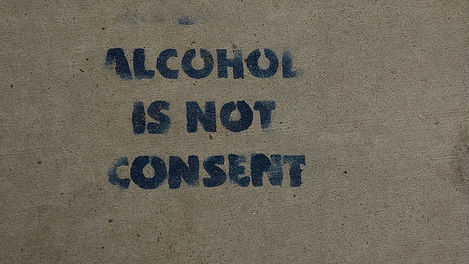

Many incidents fall in between the brutally, unimaginably violent, and the ecstatically consensual. Rape is an act of violence, not desire, but it anchors the extreme end of the spectrum of consent. It’s the most grievous, profound, felonious example of non-consent to sexual contact.

We think of consent and violence as an opposition but it’s more like a spectrum. A man I knew in my 20s told me of feeling mildly haunted by a sexual experience he’d had, in which he still wasn’t sure if his friend really wanted to have sex. (This isn’t the kind of conversation between men and women that happens often, but maybe it should). Nothing was said about it, and not a lot of words were exchanged. There was no “no,” but nor was there much of a “yes” feeling to it. Had he forced the issue? He still wasn’t sure…. A woman recalls her experiences with a long-term boyfriend in high school. They weren’t violent but, in her mind, nor did they meet a high but reasonable benchmark of consent. She had an impaired capacity to understand what she wanted, partly owing to a childhood history of sexual abuse; she didn’t feel that she had a plausible social option to say no; and she didn’t give sex much thought one way or another. She just thought sex was something that happened to you. Looking back, her experiences, she felt, “were on a spectrum—a spectrum of not-consensual.”

A Kaiser survey some years ago asked young women why they had sex—what inspired their consent. It’s a basic, overlooked question. Forty-five percent (45%) said they had sex because “the other person wanted to;” 28% did it to “make the relationship stronger;” 16% because “many of their friends had.” I kept expecting to read something like, “I had sex because it felt good” or “I did it because I wanted to.”

What do we callthese experiences? They seem to fall in a range—where not-violent, not-illegal sex is being had in the spirit of appeasement or acquiescence, or with ambiguous desire, at best.

If we had a substantive definition of women’s consent—for one possibility among many, that consent means a woman wants to have sex for its own sake, without other financial, social, emotional pressures and incentives involved—then these encounters might fall on the spectrum.

To be clear: I’m not arguing that having sex because your boyfriend whines you into it is an act of rape, or even “victimization,” whatever that word means. Many of us would have rap sheets a mile long if there were laws against mercy sex—or boring, buzzed, thoughtless, exigent, careless, stupid, and quid pro quo sex.

If an encounter falls short of a consent ideal that doesn’t mean it therefore becomes illegal, or an act of violence, or a moment that reduces the woman to the now-ridiculed category of “victim.” An incident could be legal and non-violent, and even chosen, but still fall short of the consent bull’s eye.

This is part of the problem. The dichotomies that grid and organize the sexual universe—legal/illegal; violent/non-violent; victim/non-victim—keep us from recognizing what affirmative consent would look like; in other words, how we’d think about consent if it were treated as something more substantive, material, and tangible than just the vague negative space surrounding the illegal, violent, and coercive.

And without this substantive, robust concept of consent, we can’t understand clearly what “no” means, either. The terms are made legible in relation to each other. Without the capacity to say yes, the capacity to “just say no” and to have it be respected gets unstable, too, because it’s assumed that women’s sexuality—their “yes”—is coy, disingenuous, inscrutable, or prohibited. Scholar Susan Rose discovered this in research with Dutch and U.S. teens. To the Dutch teenagers, “no means no” made sense. “When someone says no that means no.”But to U.S. teens, bothboys and girls, no was mired in fine print. They gave the “it all depends” answer. Whether no really meant no depended on a variety of factors: how forcefully or frequently she said no, whether she was giving double messages, either verbally or non-verbally, what the girl was wearing, and how she was acting when she said no.

We need a concept of sexual subjectification that’s just as vigilant, observant, and vital as feminist critiques of sexual objectification. (Although even that voice against old-fashioned “objectification” is pretty weak. As a writer in the UK Guardian laments, while she used to think feminists were annoyingly “strident” in their sexual politics, she now misses their voice against the pornographic objectification she sees every day.)

I know it sounds scary—that we should be advocating out loud that women have sex lives, or not, of their own choosing and design—but now isn’t the time to shirk from the elephant in the room principle of sexual agency, realized in full. Failure to do so—to defend “yes”—indirectly exacerbates the rape culture in which “no” isn’t respected.

Being subjectified doesn’t mean having (more) sex. Increasingly, in the hyper-sexualized day and the Viagra regime, it doesn’t feel like a genuine option to choose celibacy, but if we lived in a more pro-sex culture, this would be a legitimate, respected, non-pathologized stance, too, for people who didn’t want to have sex, and who were able to arrive at that position without subtle coercion, or for reasons other than the degradation of women’s sexual desires generally as gross and abhorrent. The relevant thing isn’t which action gets chosen—sex, or not—but that a choice gets made that meets a high instead of a weak standard of consent. Consent would mean something more than “not-violent, not-coercive, and not-illegal.”

Sexual agency gets defended and highlighted in some feminist communities. But subjectification needs to be a proud, conspicuous part of mainstream feminism, especially in reproductive politics. Too often, defenders of abortion rights point to non-consensual examples of violence or “women’s health” concerns to make their case. Victims of sexual violence, or women who need abortions or birth control for health reasons, are obviously important. But we need to stand up for women who have non-procreative sex that they desire, and who use birth control for this rather obvious but largely unspoken purpose. The fear of even rhetorically highlighting this subject makes abortion rights activists appear embarrassed and ashamed about women’s sexual agency.

It also makes them seem as disingenuous as the anti-abortion folks when they claim that their only concern, really, when they mandate that abortion clinics have extravagant, unnecessary hospital-grade design features and facilities is “women’s health.” Both hide behind the skirts of women’s health, and the dodge is equally lame in both cases.