How Kindle Promotes Bad Book-Reading Hygiene

To buy Stephen King’s latest novel, Joyland, you’ll have to go to an actual bookstore in an actual place. He’s not e-publishing it.

I got my first Kindle 18 months ago, as a gift. Since then I’ve read 82 e-books on it, depending on how expansively you define “read” and “book.”

I’ll get the positive things about my e-reader experience out of the way first: Kindle allows me to take trips without lugging several books. This leaves more space in my suitcase to lug several dresses, instead.

E-readers might also slowly be resuscitating an endangered genre that I cherish: the long-form essay. E-readers allow a piece to be its organic, natural length, rather than grossly fattened up into a book when it was supposed to be an article, or brutally slashed into an article when it was supposed to be a book. Kindle frees pieces from generic distortion in the economy of conventional publishing.

On the down side, it’s my impression as a non-technophile that Kindle is promoting bad book-reading hygiene.

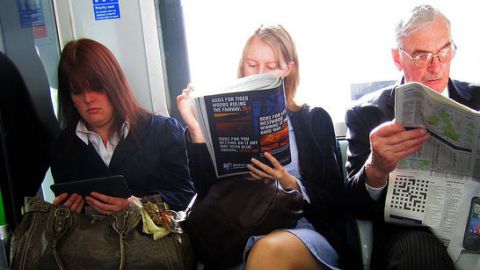

Racing to the Finish, and Reading Linearly for the Plot. Morphologically, my Kindle belongs to the genus of handheld devices and tablets more than that of books or libraries. And it’s almost Pavlovian by now to consume on-screen information by briskly clicking, scrolling, or otherwise refreshing a screen when we’re in front of one. It’s what we do during screen time, after all. With my Kindle, this inclination toward novelty and rapid clicking informs my reading. I have a sense of rushing forward in a straight line toward the end.

A mystery or thriller, even by an author I admire such as Laura Lippman, tends to get read on Kindle. This makes sense. Given its bias toward linearity and efficient movement from point A to endpoint B, the Kindle works best for me with plot-driven works, or when I’m reading for the plot, and I have lower expectations for intellectual provocation.

True, nothing prevents me from lingering on Loc. 3274, where I currently find myself in an e-book. In reality, however, it doesn’t happen. My Kindle screen is a cold, ascetic place. I’d no more linger on its page than I’d hang out at an airport security gate, or a dentist’s waiting room. The Kindle’s form invites a more linear reading experience for me than reading a book in hand, which more richly engages all of my senses.

Paper-Worthy versus Kindle-Fodder: New Book Hierarchies. I usually have multiple books going on at once and, post-Kindle, they seem to have sorted themselves through literary triage into a revealing hierarchy.

Books that feel timely and perishable—those related to current affairs—get triaged to Kindle. Right now I’m reading Gary Greenberg’s The Book of Woe on Kindle, and enjoying it, although I’m only 44% through, as Kindle lets me know with… not the “turn” of the page but the thumb flick of the screen. The book is about the profoundly troubled creation of the DSM-5.

Keyed as the book is to current affairs, I wasn’t as invested in having it in my permanent collection, rubbing elbows with Moby Dick. I have 1,574 books in our home, and need to be judicious about new acquisitions, because I refuse to cull my book herd. The minute I wrest an obscure, surely irrelevant book from my cold dead hands, I discover the next week that it is precisely the obscure, suddenly relevant book that I need.

Meanwhile, I’ve been reading a few paper books, including Good Prose, by Tracy Kidder and Richard Todd. This book on the craft of writing nonfiction achieves the rare feat of being pragmatically valuable as well as a thoroughly charming portrait of an exemplary editor-writer collaboration and friendship, sure to produce editor-envy in all writers who read it. I knew that I’d want this book in my library, and that it would provide many non-perishable, insightful moments that I’d savor and revisit, so it was paper-worthy.

Other books are Kindle fodder in my new reification of book inequality. I worry that Kindle has done the literary equivalent of introducing Doritos into my pantry. The e-reader beckons me with the latest book on debonair serial killers, or cats. I know that I should be consuming the rest of Robert Caro’s Johnson biography, but the Doritos are irresistible, and Kindle allows my guilty reading pleasures to be pursued illicitly, and with no shelf space apportioned.

No Talking Back to the Book. Kindle has a note-taking function. I can even make my marginalia public. Kindle recommends this for “thought leaders.” In another example of technology ennobling ephemera and throwaway comments–the Bullshit Turd on a Pedestal effect—people can even “follow” someone’s margin notes, and read whatever it is that they would have scribbled in the real margins of a real book, as if these comments had intellectual gravitas. What’s next, publicly-shared grocery lists?

Perhaps over time, I’d learn to use the note-taking function, but in the first 18 months, I haven’t used it once. There have been moments when I wanted to talk back to my e-book. Reading is a contact sport for me. It’s interactive. Maybe my Kindle doesn’t actually support note-taking functions, although it does allow me to highlight, a more passive activity. I’ve yet to see the note-taking option pop up when I need it, despite my liberal touching of the screen. All the inappropriate touches like as not get me jumped to a whole new chapter, or another random location. And the note-making moment is gone.

Its inelegant note-taking design makes my e-reading a more passive experience. It has more kinship than a book with the realm of watching, and consuming.

More Trees, Less Forest. I’ve also noticed that e-reading has diminished my attention to a book’s inner logic and recursive qualities, the ways that a book builds on itself, has its own order, and is self-referential. Certainly, I could thumb back screen by screen to try to find earlier passages, but realistically, the paging-through ease of a hard copy is missing. The ungainliness of back-browsing means that my e-reading is more superficial, attuned mostly to the Loc I’m on. Because it’s harder to browse, I don’t appreciate e-books as much for their architectonics, or their recurrent motifs and intra-textual allusions and echoes.

A Troubling Quantification of Reading. Speaking of Loc, I’m unnerved by the data in the lower left corner of my Kindle. It informs me of the hours of reading time remaining in the book, as well as the minutes of reading time still left in the chapter. I don’t need to be the object of a literary time-motion study. The data assumes that we read each page mechanically, at the same rate, as if no passage is more challenging, demanding, or enticing than another. Ideally, reading is a meander, with fits and detours. Kindle’s data imagines it like a goose-step military march through the pages at a perfectly-paced rate.

Over time, to a mildly Type A sort like myself, it could even become tempting to out-race the proposed “minutes left of reading time,” to see if I could nudge it down. Over time, the data could become prescriptive; to wit, “spend five more hours on this book, then you’re done, unless you’re suffering from early onset dementia that’s slowed down your usual comprehension rate.”

In another move toward the quantification of the reading experience, I’m also informed of the percent of reading material I’ve consumed. To say I’m “32% done with it” doesn’t have the quaint charm of saying, “I’m absorbed in a great novel.” Certainly, people get anxious to know where they are in the wilds of a book. But the update as to your percent consumed suggests that reading is about the finish. Reading isn’t best done—or the best reading done—when it’s timed.

The Book Deracinated. Kindle lacks the small touches that make me feel in communion with the author—especially her photograph on the jacket—so the reading experience feels deracinated, or less intimate. It may be weird, but I like to be able to easily flip back to the author’s photograph while I’m reading, perhaps to remind myself of her human presence.

Or, consider a book’s size, dimensions, font, and design. All these elements signal what sort of book the author thinks hers is. When I proposed a new book idea a writer friend made a gap with her thumb and index finger to indicate thickness, and asked, “is it a THIS size book you have in mind?” Size signals content: Is a book a small, light thing to be sold at the register, or a serious tome? How the book looks, in font and design, informs the contract that we forge with the author before we even start reading.

The Kindle has given me some reading satisfaction, but I’m doing a reverse commute on the information superhighway. I’m gravitating back to books, but will choose scrupulously.