Trust the Results, Not the Conclusions

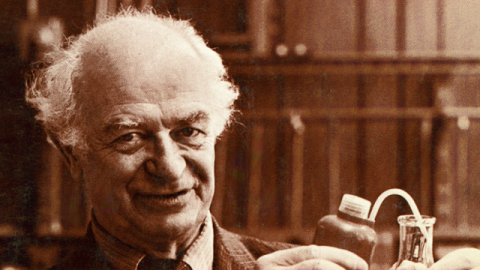

Very early in my writing career I was fortunate to be able to spend three hours interviewing Linus Pauling (above), the only person in history to win two unshared Nobel Prizes. One of many things I learned during that interview process that has stayed with me ever since has to do with interpretation of scientific results.

Pauling was roundly criticized, in his later years, for his controversial stance on vitamin C. (He came to believe that vitamin C not only could prevent and/or cure the common cold but could protect people from more serious diseases as well.) I interviewed Pauling at length on the subject. He told me that when he first began researching the role of vitamin C in protecting against the common cold, he was struck by how many papers he encountered in the scientific literature that showed a divergence between the results obtained and the conclusions drawn. Authors, he found, tended to fashion conclusions around their own belief biases as much as around the actual data they reported. Pauling regularly encountered studies in which the data clearly showed a positive effect for vitamin C, but because the effect was judged insignificant by the studies’ authors, it wasn’t discussed in the conclusion (nor the abstract, usually) of the paper(s) in question.

What’s so insidious about this is that other researchers who cite a given study will tend to quote from the conclusions section of a study, or the abstract (seldom the results), thereby propagating the authors’ original biases.

I’ve seen this myself, over and over again. Propagation of incorrect conclusions has played an important role in, for example, the misplaced belief in the greater readability of serif fonts over sans-serif fonts. (For details, see “The Serif Readability Myth.”) Another example that comes readily to mind is the 2001 National Cancer Institute report that is so often cited to show that low-tar cigarets are just as harmful as regular cigarets: “Risks Associated With Smoking Cigarettes With Low Machine-Measured Yields of Tar and Nicotine” (National Cancer Institute; 2001. Smoking and Tobacco Control Monograph 13). Chapter 4 of this monograph presents a great deal of convincing evidence that today’s filtered low-tar cigarets are much less toxic than the unfiltered high-tar cigarets of 60 years ago. And yet the monograph is often cited as showing the opposite.

And then there are drug studies like the one by Berman et al. in J. Clin. Psychiatry 2007 68:843-853 that confuse statistical significance with clinical significance, reaching a positive conclusion on the basis of the most miniscule effect simply because the effect was statistically valid. In the Berman study, which is often cited as proving the effectiveness of Abilify when used as an adjunctive treatment in depression, patients who failed to show improvement on standard antidepressants (SSRIs, SNRIs) were given Abilify (or placebo) augmentation for 6 weeks. The authors defined failure to show improvement on antidepressants as failure to experience a 50% reduction in score on the Hamilton rating scale (a common depression assessment test) after taking antidepressants. But when patients were given adjunctive Abilify for six weeks, they still failed to show 50% improvement on their test scores. (The treatment group’s average improvement was 34%, which sounds impressive until you realize that the placebo group improved 22%.) The net gain provided by Abilify was 3.0 points on the Montgomery scale, which, in the UK, is the absolute lower limit on what’s considered clinically significant for drug-approval purposes. Also, this 3-point gain was an average, based mostly on improvement in female subjects. Male subjects hardly saw any benefit. All in all, the paper showed Abilify to be remarkably inert, little more than a super-placebo where depression is concerned. Yet somehow the authors of this drug-company-funded study saw fit to conclude that “adjunctive aripiprazole was efficacious and well tolerated,” and Abilify is now a top-selling drug in the U.S.

The bottom line, in any case, is simple. Read studies carefully to see what the results actually are or were; then analyze the results yourself. Don’t just read a paper’s Abstract and the Conclusion. You may very well be misled.