Will Life Extension Mean the End of Religion?

I’ve been thinking in speculative directions lately, and nothing is more speculative than the question of whether we’ll one day be able to extend the human lifespan. The notion of living longer is certainly pleasant to contemplate personally, but I’m not convinced it would be positive for humanity as a whole. As I wrote in “Who Wants to Live Forever?“, the invention of anti-aging therapy could be a disaster, if it freezes the human race’s moral opinions exactly as they are now: imagine North Korea as a cult state worshipping an immortal tyrant in fact and not just in ideology. And then there are the ecological implications, as in Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars trilogy, where the invention of an anti-senescence therapy catapults the Earth into a disastrous “hypermalthusian” era.

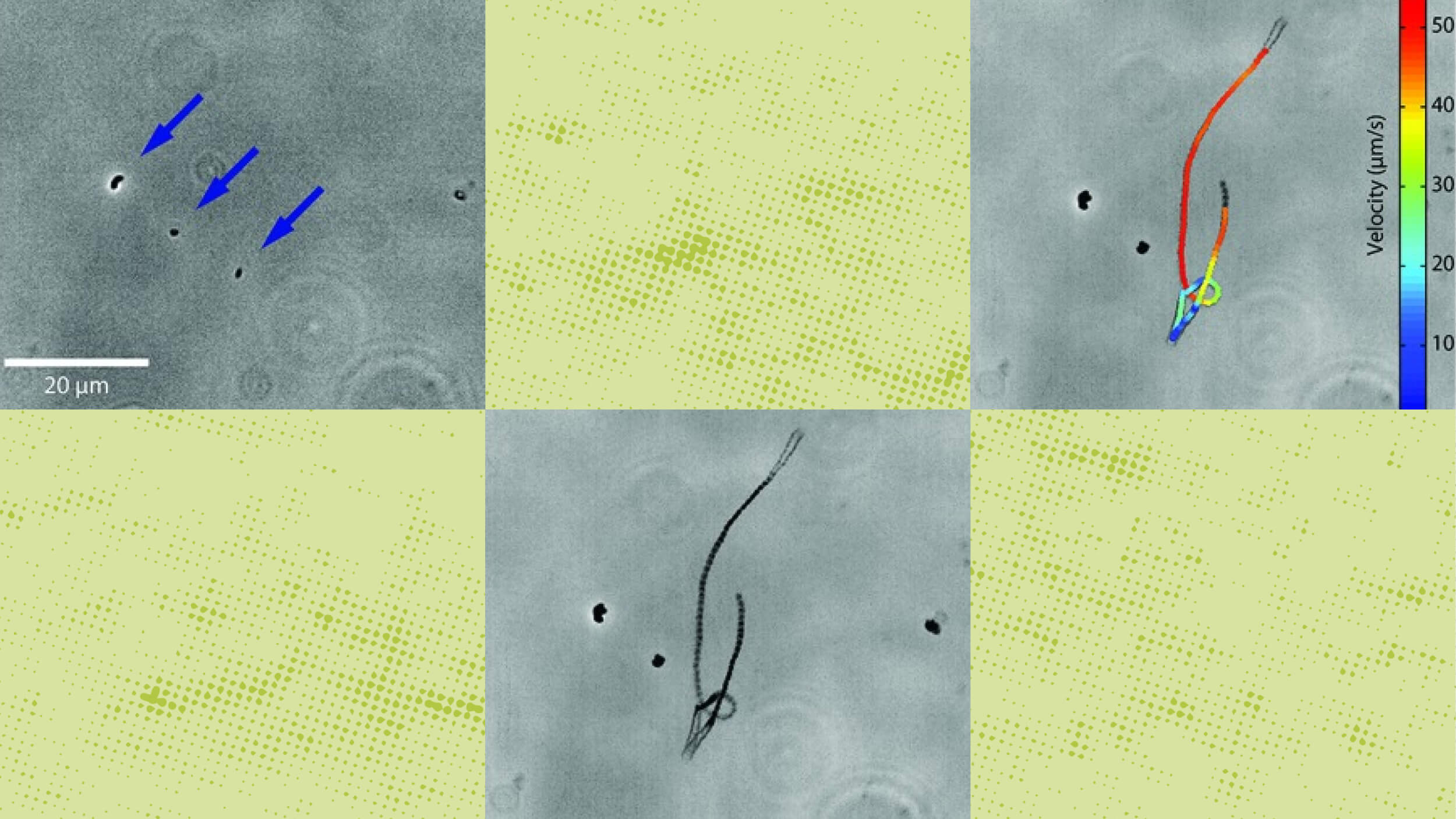

But whatever the moral or political implications of immortality, I have no doubt that it’s possible. There are any number of species in nature that exhibit negligible senescence, and some that have even more impressive tricks: like Turritopsis nutricula, a jellyfish that can revert from its adult, free-swimming medusa form back into its larval polyp form, as if an adult could age in reverse and turn back into a child.

Given these natural templates to study, I have little doubt that human beings will eventually invent a therapy that prevents aging, maybe even one that reverses it. I’m not saying I expect this to happen in my lifetime; in fact, I think it probably won’t. (Ending death is a noble goal, but I suspect the life-extension advocates who argue that it’s just around the corner are falling prey to wishful thinking. This particularly applies to those who are trying to stay alive until it happens, like Ray Kurzweil and his bizarre, unproven 150-pill regimen.)

But when we invent a real treatment for aging – when we can stop people from growing old, when we can rejuvenate ourselves at will – that will be the acid test of whether most religious people really believe what they say they do. Most religions teach that death is only the gateway into another realm of existence, one so blissful that we should envy the dead rather than mourn them. In a world where death is inevitable, that may be a comforting belief. But what happens when death is no longer inevitable? What will happen in a world where, barring rare accidents, people must choose to die? Will theists choose their faith in an afterlife over the certainty of an earthly life?

My guess is that when life-extending technology is invented, the clerics and fundamentalists – the people most invested in religious belief – will denounce it as the ultimate violation of God’s plan, and will probably outlaw it wherever they have the power; but the vast majority of ordinary people, religious or not, will be clamoring for it. And I think this may be the wedge that splits religion once and for all.

Past and present moral struggles, like the revolutions in women’s rights, racial justice and gay rights, have diminished the moral authority of the churches that resisted them. But the impact of this one will be far greater, because it affects everyone. Most churchgoers aren’t directly affected by issues of racial discrimination or marriage equality, so they can afford to ignore what their church teaches about them, but when your pastor tells you that you have to stop taking the medicine that’s keeping you alive, people tend to take that sort of thing personally. When you combine this with the observation that people with more secure, prosperous lives see less need for the consolations of religion – and people who have no fear of death are the logical culmination of this – the invention of an anti-aging therapy could well lead to a massive exodus from the churches.

The question then becomes, what will happen to the people who stay behind? Obviously, those who refuse the treatment will age and die off as humanity always has. Normally, they’d propagate their beliefs by passing them on to their children – except I suspect that, as with every other social advance, anti-aging therapy will seem completely normal to those who grow up with it, and the previous generation’s resistance will look like irrational prejudice. And if that next generation opts for the treatment and ends up leaving or getting kicked out of their churches, leaving their stubborn elders to commit suicide by aging, it may well be that the invention of rejuvenation will mean the end of religion as we currently know it.

The invention of true immortality will be a sharp discontinuity with everything that came before, demanding a completely new model of human life and society. There are bound to be holdouts: I’m sure some religious fundamentalists and others will retreat into isolated enclaves, trying to keep their children even from finding out that such a technology exists, but these bubbles will inevitably erode. I don’t want to be excessively optimistic – as I said, the arrival of immortality will bring with it an array of completely new problems, some far more serious than anything it cures. But when that day does come, I think, it will be the humanists who inherit the earth.

Image credit: shutterstock.com