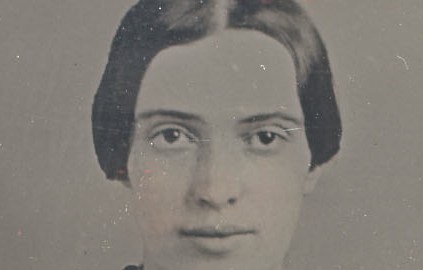

A New Photo of Emily Dickinson? Well—Maybe—

Only two authenticated images of Emily Dickinson exist: one a painting of her (and her siblings) as a child, the other an iconic photograph of her as a teenager. In the past fifty years twoimages have gained publicity as possible “new” photos of the poet; both have largely been discredited, though the jury is still officially out on the second. Now the Amherst Archives and Special Collections reports that yet another daguerreotype has surfaced, and at least one expert is claiming it’s the real thing.

Dr. Susan Pepin, Director of Neuro-Ophthalmology at Dartmouth Medical School, has conducted a close anatomical comparison of teenaged Emily and the mystery woman. Her conclusion: “I believe strongly that these are the same people.” (The report is full of startlingly precise details, suitable for lending a scientific luster to English class presentations. Did you know that Emily Dickinson had a “prominent left nasolabial fold”? Now you do.)

The candidate photograph has been dated to the late 1850s; the sitter under scrutiny looks to be in her late twenties or early thirties. (The timeline fits: Dickinson was born in 1830.) The dress she’s wearing was a decade out of fashion at the time, which for Dickinson sounds about right. Her fellow sitter has been identified as Kate Scott Turner, a friend of the poet’s. The mystery woman has a larger chin than teenaged Emily, and a smaller nose in proportion to the lips, but the eyes are strikingly similar.

Of the two women, Kate is the one with a thousand-yard stare. (She’d been recently widowed.) But look closer at her friend: there’s something peculiar about that gaze. The pupils are asymmetrical, as they are in the known photo—Emily may have suffered from both astigmatism and iritis—but they’re also large, dreamy, and a little amused. Dickinson once compared her eyes to “the Sherry in the Glass, that the Guest leaves”; the woman in the picture just about lives up to the simile.

Why care if it’s Dickinson or not? Literature has few saints and even fewer true enigmas, since biography tends to air whatever the books kept hidden. But beginning in the 1860s, Emily Dickinson disappeared almost entirely into her writing, spinning a myth around herself that even her best biographer, Richard Sewall, couldn’t fully untangle. She shut the door on a normal life and became a poet, full stop. Even her letters are prose poetry. Her work from 1861 through 1865 is one of the great explosions of creative energy in the history of the arts, as well as one of the great records of trauma absorbed and outlived. (Scholars have blamed her early-thirties crisis on everything from manic depression to epilepsy to psychosomatic blindness to unrequited love, but none of these diagnoses seems adequate to the scope of the poetry.) She’s a heroic and tragic figure, and the essence of both her heroism and her tragedy is her unavailability to us outside the work.

A new photograph would bring us just a little closer. Look: the mystery woman has even thrown an arm around her friend, a gesture we can hardly imagine the Recluse of Amherst making. If she was on the cusp of crisis, it doesn’t show yet. In my heart of hearts I doubt it’s Emily—that chin just doesn’t match up—but pending further reports on clothing samples, image records, nasolabial folds, etc., I’ll keep believing and disbelieving at once, which, as Emily said, “keeps Believing nimble.”

[Image detail courtesy Amherst Archives and Special Collections. Full, enlargeable image available at Book Haven.]