Why Rodin Is Dangerous Again

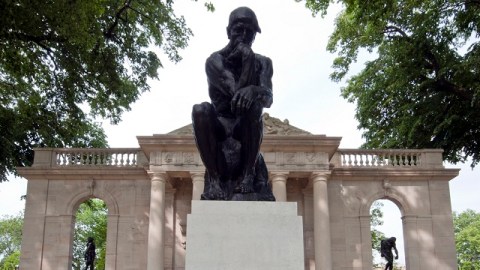

“Danger: Art Inside,” read the labels on the crated sculptures as I toured last month the almost-ready-for-public-viewing, but now restored, reinstalled, and reinterpreted Rodin Museum in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The signs warned workers to take special care around pieces that couldn’t be moved during the renovation, but the same warning should be plastered across the façade (shown above) replicating that of Auguste Rodin’s Château d’Issy home in Meudon, just outside Paris. By restoring the look of the museum from its opening in 1929 and reimagining how to present Rodin’s art for the 21st century, the team at the the Philadelphia Museum of Art, which has overseen the Rodin Museum since 1939, pays tribute to the vision of Rodin collector and champion Jules Mastbaum. Mastbaum’s, whose collection makes the Philadelphia site the second largest Rodin museum in the world, made made his fortune in the movie theaters, so there’s no doubt that he’d love this new summer blockbuster.

Mastbaum first fell in love with the art of Rodin when a small sculpture by the master in a store window caught his eye in 1923. The movie magnate began to obsessively collect everything he could by Rodin, ordering castings of all the major works for what would be his museum back in his home town of Philadelphia. Sadly, Mastbaum died in 1926, three years before the museum opened as one of the first major projects completed on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. The museum’s classically influenced design of architect Paul Cret and landscape designer Jacques Gréber has graced the Parkway for more than eight decades since.

Unfortunately, those decades haven’t always been good ones. The museum stood open for just a few years before The Great Depression struck. Rodin’s rollercoaster reputation—global during his famous/infamous lifetime, ridiculed after World War I, and shaky until solid rediscovery as the father of modern sculpture in the 1950s and 60s—didn’t help matters.

I remember visiting the museum while in college in the 1980s. A lone guard sat beneath an industrial-sized fan in the sweltering, air condition-less gallery. Gréber’s grounds were overgrown with weeds. The fountain and reflecting pool lay dry. The famous Thinker—muscular, meditative, and almost minty with corrosion thanks to years of acid rain—greeted you at the gate almost with chagrin. It was embarrassing to see this magnificent collection housed in such misery. PMA curator Joseph Rishel, who has worked with the Rodin Museum since 1972 and oversaw the restoration, stressed that there were “no villains” behind the deprivations of the down years, only the stark reality of underfunding of the arts. Thankfully, the money was found to bring the museum back to life.

PMA curator Jenny Thompson spearheaded the effort to “activate” the collection again. A conservation team painstakingly and meticulously researched and restored the outside grounds, building exteriors, and gallery interiors to their late Roaring Twenties glory. The pale linen walls and chocolate-brown trim of the main room and end galleries give a feeling of openness enhanced by the restored giant skylight. A long side room of warm wooden floors and walls flooded with light by large windows features smaller works by Rodin, such as an assemblage of heads and other pieces from The Burghers of Callais, which seems almost like a visual analogue to Rodin’s working method of playing mix and match with body parts and even whole figures. Even a work as minor as a scene from the French Revolution for an unrealized monument project draws your interest when you realize you’re looking at Rodin’s fingerprints still visible in the wax. These intimate works in the intimate setting give you the best sense of the artist’s magical touch.

But the real activity of the activating mission happens in the big room and the two corner rooms. In the main room, Jenny Thompson has assembled the individual pieces that together comprise The Gates of Hell, a full cast of which appears at the museum’s entrance (and which is the next big restoration project after The Burghers of Callais). The Kiss commands the room by size and sexiness, but doesn’t dominate the way that The Burghers did for decades after coming inside out of the acid rain. With The Burghers outside once more, the room seems more open and flexible. Sitting upon the original pedestals, works such as I Am Beautiful dazzle. The passionate tension of The Gates of Hell resonates fully through the selection of pieces. Rodin’s suffers from the Valentine’s Day misuse of The Kiss and other sculpted lovers. The Kiss comes from The Gates of Hell, where the lovers embrace among the flames as “a beautiful way to burn.” Torment and pleasure exist simultaneously. The title of the piece Shame (Absolution) beautifully embodies this dual nature and Rodin’s emotional and intellectual depth. Just as a man and woman emerge from Rodin’s Hand of God, bared, true humanity emerges from the art of Rodin even in the most otherworldly settings.

In the one corner room (beautifully restored to its original crimson with cream and grey trim), all of Rodin’s sculptures of the French author Balzac appear, including the controversial monument. However, what fascinated me most about the room was the comfy sofa inviting visitors to sit and either draw or write as the spirit moved them. I sat and sketched Rodin’s Colossal Head of Balzac for a few minutes and felt inspired and refreshed by sharing in the overflowing creativity all around. Activating the collection clearly translates into activating the visitor with such gestures. I left my sketch in the book, but I took away a much more valuable experience—a dangerous (in a good way) thing especially for young people.

Mastbaum knew movies, which probably helped him see the cinematic quality of Rodin’s art. It grabs you in a way independent of language, culture, or time, just as a great film can. The ability to cross those boundaries challenges the mind and puts in danger simple generalizations about human motivations and feelings. By rebooting the Rodin Museum, the PMA strips Rodin of the sentimentality built up over the years and reveals the real Rodin—mad, bad, and dangerous (but essential) to know.

[Image: Rodin Museum, Meudon Gate and The Thinker, 2012. Photograph courtesy Philadelphia Museum of Art.]

[Many thanks to the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Rodin Museum for the image above, other press materials, and an invitation to the press preview of the grand reopening on July 13, 2012.]