Why Does George Bellows Take Such a Critical Beating?

You’d think that a giant retrospective at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC would, at least momentarily, make George Bellows the king of the art ring. But once again Bellows finds himself the disputed champion of the sports-related paintings that made him an acclaimed artist in his own time before his tragic death at the too-young age of 42. The New Yorker’s Peter Schjeldahl’s review (titled “Young and Gifted”) raises the typical and, I believe, unfair criticisms of Bellows, who is too often diminished for the things he wasn’t and not often considered for the things that he was in the short time he had to do them. For someone who should stand among the first rank of American artists, why does George Bellows take such a critical beating?

Of all the members of The Eight, Bellows is my favorite, just edging out Robert Henri. They preferred the name “The Eight” over the name imposed on them by the critics, “The Ashcan School.” Because The Eight chose to depict early 20th century American life of the middle and lower classes, the critics back then figuratively threw them into the dumpster—a critical form of class warfare. Bellows, who almost became a professional baseball player rather than a painter, painted the rough, yet beautiful streets of New York City and its people conducting their lives—gathering on election nights, swimming for recreation, and, most memorably, watching the then-illegal sport of boxing.

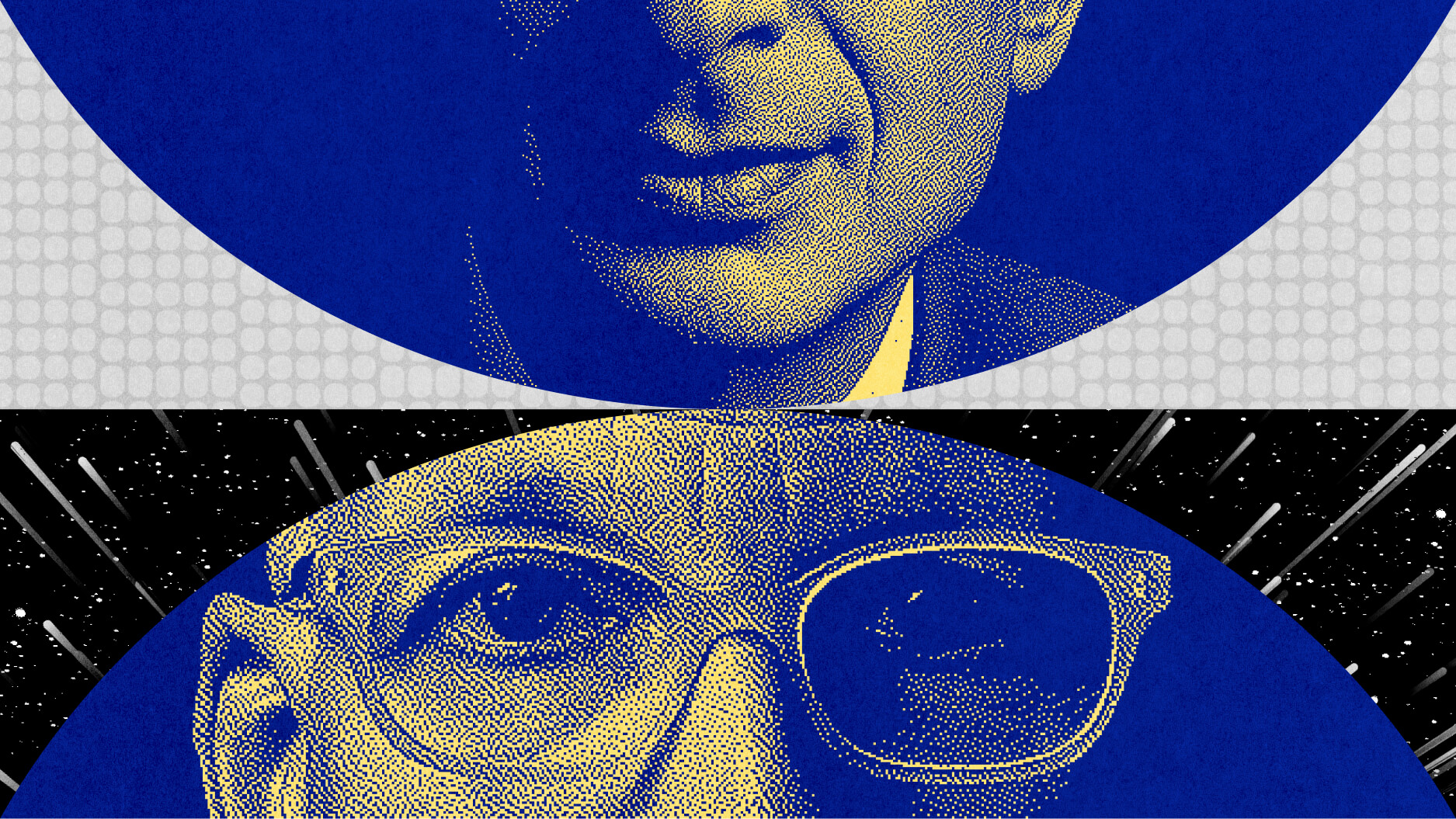

To get around the law, private clubs would host fights between “members”—combatants who would “join” simply to battle before other “members” in attendance. Marquess of Queensberry rules did not apply. Bellows painted such scenes as only a “member” in attendance could. The boxing paintings fill a whole gallery in the NGA exhibition, with Stag at Sharkey’s (shown above, from 1909) perhaps the best. Even Schjeldahl admits that the “eloquent—fast, sensuous, subtle” brushwork “feel[s] prophetic of Willem de Kooning.” It’s a portrait of America’s earliest vicarious living through sport—a mirror image of the brutality of American life at the time as well as the glorification of the individual striving for glory. For better or worse, it’s one of the most significant and telling pictures of the first half of the what’s known now as “The American Century.”

But Bellows was much more than just a boxing painter. Excavation at Night shows the digging of the foundation of Grand Central Station in a eerily beautiful image of a construction site transformed by moonlight. Blue Snow, The Battery and other urban snow paintings similarly use a wintry cover to transform the urban landscape—not to cover over the real thing, but to enhance and emphasize the hidden beauty already there. Summer Surf and other seaside paintings depicting the raging sea colliding with rock and sand give Winslow Homer a run for his money. A lithograph of Billy Sunday preaching in his forceful style captures him almost leaping across the pulpit like a boxer lunging to strike the final blow. There’s a variety of subjects in Bellows art, but all with the same kind of vitality.

But what does the typical Schjeldahl-esque critic focus on? Bellows, like many others during the run-up to America’s involvement in World War I, fell for the propaganda of German atrocities propagated to drum up popular support. Bellow’s fervor took the form of illustrations giving life to those fictions. Schjeldahl sees those works as Bellows “sacrifice[ing] his integrity” to war fever after initially opposing American involvement. What he and other critics leave out, however, is Bellows continued support for conscientious objectors to the war, even after he gave his own approval. It’s easier to depict Bellows as a blind follower, but the truth’s a little more complex, just as most truths about Bellows are.

What irked me the most about Schjeldahl’s review was the odd indictment that Bellows was no Edward Hopper. Few ever were. It’s really a false comparison. The two artists had different goals, different styles, and different opportunities. Would a Hopper dead at 42 be the Hopper we know today? It’s the same critical class warfare that spawned the “Ashcan” label a century ago, but much subtler. It’s purely coincidence that sports painter Leroy Neiman passed away this week, but Schjeldahl’s “postscript” mixture of faint praise and critical condescension sounds a lot like his take on Bellows. Schjeldahl would surely admit that Bellows is much better than Neiman, but throwing Bellows in the ring with Hopper is an unfair fight—to both artists. The show George Bellows might finally give Bellows a fair chance, under the fair rules of public scrutiny, to win his fair share of praise.

[Image:George Bellows. Stag at Sharkey’s, 1909. Oil on canvas. Framed: 110.17 x 140.5 x 8.5 cm (43 3/8 x 55 5/16 x 3 3/8 in.). Unframed: 92 x 122.6 cm (36 1/4 x 48 1/4 in.). The Cleveland Museum of Art, Hinman B. Hurlbut Collection.]

[Many thanks to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, for providing the image above and other press materials related to the exhibition George Bellows, which runs through October 8, 2012.]