What Kind of Artistic Afterlife Will Thomas Kinkade Have?

The self-titled and legally trademarked “Painter of Light” has been extinguished. When the news spread on Saturday that painter Thomas Kinkade had suddenly passed away at the age of 54 of natural causes, it sent a tremor through not necessarily the art world, but more like the art critic world. Obituaries remained for the most part politely silent on Kinkade’s quality as a painter and his questionable business dealings, going by the “speak no ill of the dead” policy rather than dancing on his yet to be dug grave. I’m not much of a dancer and see no point in rehashing past sins, so, instead, I’ll think about Kinkade’s posthumous future. What kind of artistic afterlife will Thomas Kinkade have?

I’m no saint and certainly no St. Peter, so I won’t speculate on where Kinkade will spend eternity. However, as can be seen in the reader comments to Kinkade’s obituaries, some want to damn “The Painter of Light” and his sentimental art to Hell’s eternal darkness, while others want to canonize Kinkade with a rush of admiration not only for his art, but also for his spirituality. While the obituaries have been tame, the commenters have been particularly savage to Kinkade and to one another.

If you love Kinkade’s art and, perhaps, own some of it, then you most likely buy into his heartland sentimentality that mixed equal parts of Christianity and American patriotism. Kinkade’s persona as a man of faith sold his work as much as his skill as a painter. Those who bought franchises to sell his works claim that they invested based on Kinkade’s personal Christianity as much as on hopes of financial gain. People who trained to sell prints and reproductions of Kinkade’s art sounded more like acolytes than art appraisers. Kinkade’s art became a religious experience as the works would “glow” in dimmed light, usually closing the deal for those with lingering doubts over buying.

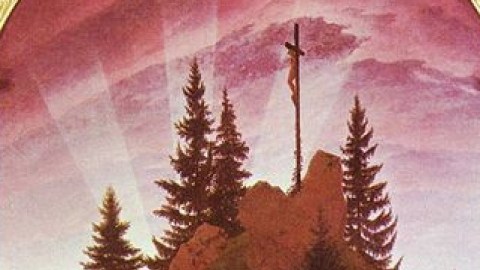

If you hate Kinkade’s art, then you find the technique abysmal and the combination of Christianity and American idealism shallow and superficial. Critics often point toward artists such as Caspar David Friedrich (whose The Cross in the Mountains appears above) and William Holman Hunt (whose The Light of the World paintings marked the visual peak of the Victorian age’s fervent Christianity) as examples of artists who combined talent with spirituality. If you have problems with the sincerity of Kinkade’s faith based on his questionable business practices and his tangles with the law, then you sour quickly on his faith-based sales pitch and art.

I’ll admit that I’m no fan of Kinkade’s art. When I saw one of his works on the wall of a friend, I actually flinched in aesthetic pain. (By the time they plugged in the painting’s internal lighting system, I had recovered enough to be more polite.) To me, Kinkade is an artist of his time—the 1980s and 1990s America, where faith and politics became irreparably confused and confounded from the days of Reagan on. Thomas Kinkade is in many ways the Ronald Reagan of American art—praised far beyond what his skills should merit, but shrewd enough in his presentation to be given credit for salesmanship. Just as groups continue to amass as many honors as possible for St. Ronnie, no doubt admirers will advocate for posthumous honors for St. Thomas. In the long run, however, the afterlife will most likely be unkind to these heroes of the last two decades of the 20th century, aka, the American century. Thomas Kinkade, who was seen for much as his life as the solution to modern art’s elitism and secularism, will ultimately be judged as a symptom of a far greater problem of cultural myopia—a near-sightedness based on a culture that no longer strove to look either deeply or long enough at itself in decline.

[Image:Caspar David Friedrich. The Cross in the Mountains (detail), 1807.]