What Did Robert Hughes Really Teach Us?

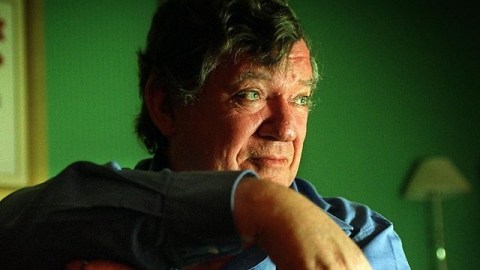

Upon hearing of the passing last week of journalist and art critic Robert Hughes (shown above), I felt like had lost a beloved teacher. For people who read Hughes’ books or articles or, more likely, saw him on television, he was the fun, brash, borderline bawdy professor whose name and face you never forget. Hughes brought modern art into your living room and made it understandable and surprisingly fun, which makes him a significant cultural figure beyond his contributions to art itself. In the end, it’s important to ask, what did Robert Hughes really teach us?

Born in Australia in 1938, Hughes failed to distinguish himself academically and, basically, hit the road as an adventurer/art critic roaming the globe and absorbing all the great art sites, which became his true college. He eventually made his way to London and wrote art criticism for the Sunday Times. His first book, 1969’s Heaven and Hell in Western Art (1969) failed miserably, but amazingly caught the eye of an executive at TIME Magazine, who hired Hughes as the in-house art critic—a role he kept for decades. Hughes moved to New York City in 1970 and kept that as his home—as much as a home he could have for all his travels—for the rest of his life.

Hughes’ real breakthrough came with the 1980 publication of The Shock of the New: Art and the Century of Change. The subsequent television series of the same name made Hughes an art star of the first magnitude. Beginning with how technology influenced art in the 1880s all the way up to end of World War I—with the corpses of the technology mad Futurists literally littering the way at the end—Hughes colorfully managed his way through modern architecture, Surrealism, and Expressionism. Shock then deals with Pop Art under the rubric of “Culture as Nature” and successfully shows the depth of Pop Art beneath the seemingly shameless use of the everyday. For me, when Hughes ends the series talking about the commercialization of modern art—and not a good kind of commercialization—he really won me over as someone who understood, appreciated, and still could castigate contemporary art when it became so much about money that the meaning was lost. Hughes’ passion never kept him from pointing out the art emperors’ lack of underwear.

I recently watched again Hughes’ 1997 television series American Visions after flipping through the companion book on my shelf. The Australian-turned-American viewed his adopted land’s culture with an outsider’s eye, making the series an entertaining and enlightening view of American art that didn’t pull punches, but also didn’t talk down in a “we still think of you as colonies,” Eurocentric kind of way. When I first watched the series in 1997, I felt that Hughes’ lingering over the American car culture of the 1950s and 60s was an unnecessary digression—a useless sidecar, if you will. Watching it again 15 years later, however, I saw how Hughes’ ability to link lowbrow with highbrow—Cadillacs with James Rosenquist—gave a truer total picture than just one half of the equation.

Critics of Hughes’ criticism always dismissed his way of exploring and (gasp) actually enjoying the less exclusive realms of culture, especially American culture. I didn’t agree with everything Hughes said (his dismissal of Andrew Wyeth, for example, but even that is excusable as a response to the hype surrounding the Helga paintings revelation that rankled Hughes even a decade later), but I did enjoy his enthusiasm and his downright manliness in the realm of art. I can’t believe that I never knew that Hughes full name was Robert Studley Forrest Hughes. Hughes the critic was always a “Studley Forrest”—a vast range of tall pines, yielding slightly but always resolute in the windstorm of opinions but always studley and macho when the stereotypes of effeminate or weak threatened to overshadow art.

Young pictures of Hughes show him with a long mane of hair—a lion in the den of art history. Hughes’ health betrayed him towards the end, but not before he wrote one last great book on Rome—an eternal kiss to the eternal city. Hughes subtitled the Rome book “a cultural, visual, and personal history,” which could be the motto for all his work. The first great TV teacher of art for me was Sir Kenneth Clark, whose Civilisation series and book seemed like the final word on art history for this teenager with a VCR machine easily impressed with a British accent. More recently, Simon Schama’s energetic, almost elfin take on art history and energetic integration of both the art and the history has held me in sway. Somewhere in between will always be Robert Hughes—the tough, fun, relentlessly authoritative, and relentlessly personal critic who put himself into every opinion, every picture. When Hughes talked about Goya’s pain, for example, it came from the depths of his own. Hughes’ pain is over, but the lesson of putting yourself into the art, of experiencing the pleasure and the pain personally, lives on.