Untangling the Web in Which Abstract Art Began

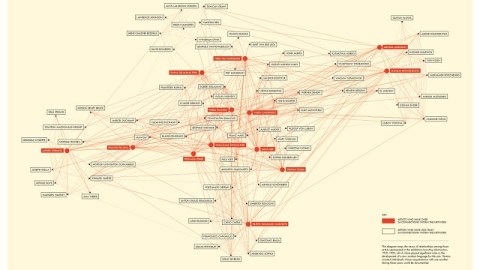

“A painter, a composer, and a poet went on a road trip,” begins one print advertisement for the MoMA’s new exhibition Inventing Abstraction: 1910-1925. Although it sounds like the start of an artsy joke (“Two Abstract Expressionists walk into a bar…”), the punchline’s serious: “…and a new art form was born.” An immensely ambitious exhibition, Inventing Abstraction aims at no less than untangling the international web of associations and influences between artists across disciplines that resulted in the paradigm shift from realism to abstraction at the beginning of the 20th century. From a distance, understanding the inner workings of that network appears as daunting as the exhibition’s diagram above, but Inventing Abstraction will have you peering through the matrix to the surprising truth lurking beneath.

The road tripping threesome of painter Francis Picabia, composer Claude Debussy, and poet Guillaume Apollinaire begin one key strand in the abstraction web in July 1912. Fresh from an all-night drinking session in Paris, the three artists got into one of Picabia’s cherished cars, drove to the coast, caught a boat to England, and crashed Picabia’s wife’s vacation. On the conversation-filled, soberer trip back to Paris, Picabia passionately defended abstraction (or, as they called it, “pure painting”): “Are blue and red unintelligible? Are not the circle and the triangle, volumes and colors, as intelligible as this table?” Picabia soon thereafter painted La Source and Danses à la source, two abstract paintings that put his ideas into practice. That multidisciplinary meeting of the minds encapsulates the overall drift of the exhibition as it tries to recreate how different artists from different media bounced ideas off of one another like overcharged electrons.

Inventing Abstraction gathers together the usual suspects when the scene of the crime of modern art is dusted for fingerprints. Vasily Kandinsky, Piet Mondrian, Kazimir Malevich, and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti provide the words behind the images, as well as many of the key images. Malevich’s Suprematist Composition: White on White still stands mightily in the midst of all this abstract color and gesture with its colorless, utterly simple statement. Likewise, Mondrian’s grids continue to bear the weight of his philosophy. Whereas Marinetti shouted manifestos from rooftops, compatriots, most significantly Umberto Boccioni (sadly represented by just one painting), put those words into art.

Two familiar figures surprise in different ways. Marcel Duchamp, despite a healthy selection of his works, doesn’t assume his customary central position in the conversation, perhaps due to the decentralizing nature of the exhibition itself, but maybe because, at least in this instance, he’s a secondary figure. Pablo Picasso pops up as a surprisingly central figure, at least in the flow of the diagram. Citing 1910’s Femme à la mandoline Cubist painting and a 1912 “Study for a Construction” drawing, the curators hope to out Picasso as a closet abstractionist, despite Picasso’s own disavowal of giving up the recognizable human figure. Although Mondrian realized that “Cubism did not accept the logical consequences of its own discoveries” in his estimation of Picasso’s abstract side, Inventing Abstraction sees a greater acceptance, at least at the beginning. Thanks to the nature of the diagram’s dynamic, Picasso’s inclusion in the web of influence might be more guilt by association, starting with his close ties to Apollinaire. In many ways, Inventing Abstraction could be called “Six Degrees of Guillaume Apollinaire.”

In addition to the big names, less heralded names find room to network in the galleries. Hans Arp’s woodcuts, painted wood sculptures, and books charm, while his better half Sophie Taeuber-Arp startles with abstraction in everything from painting to sculpture to needlepoint. Many Russian artists find places of prominence in the show, most significantly Natalia Goncharova, an underrated but challenging painter (also sadly represented by just one painting). Marsden Hartley’s wartime abstractions, including Berlin Abstraction (from 1914-1915), document a real-time response to love and loss during that epoch-changing conflict. Photographers Alfred Stieglitz and Paul Strand find abstraction in natural and urban landscapes, but photographer Alvin Langdon Coburn, with his almost kaleidoscopic Vortographs, takes photographic abstraction to another level. Even abstract dance itself is represented by choreographic diagrams by dancer-choreographers Rudolf von Laban and Mary Wigman.

Even if the fine details of the idea of Inventing Abstraction: 1910-1925, like the nitty gritty of the diagram above, elude the eye, the overall effect is unmistakable. You simply can’t pin down an origin to abstraction, other than the pervasive sense at the beginning of the 20th century that the old truths no longer were true. An homage to the MoMA’s first director Alfred H. Barr, Jr.’s 1935 diagram of “Cubism and Abstract Art,”Inventing Abstraction: 1910-1925 once again tries to connect all the dots and name all the names, proving that even if answers aren’t found, asking the questions is more than enough.

[Image: The invention of abstraction was not the inspiration of a solitary protagonist, but a relay of ideas that moved through a network of artists and intellectuals working in different countries and different media. This diagram maps the nexus of relationships among those artists represented in the exhibition Inventing Abstraction: 1910-1925, all of whom played a significant role in the development of a new modern language for the arts. Vectors connect individuals whose acquaintance with one another in the period 1910-1925 could be documented. The names in red represent those figures with the most number of connections within this group. The chart was a collaboration among the exhibition’s curatorial and design team and Paul Ingram, Kravis Professor of Business, and Mitali Banerjee, doctoral candidate, Columbia Business School. An interactive online version of this diagram can be found here.]

[Many thanks to the Museum of Modern Art, New York, for providing me with the image above and other press materials related to Inventing Abstraction: 1910-1925, which runs through April 15, 2013.]