The Ecstatic Abstract Explorer: Richard Pousette-Dart

“The extasy [sic] of abstract beauty,” artist Richard Pousette-Dart scrawled in 1981 in a notebook on a page across from a Georges Braque-looking abstract pencil drawing. Although included in Nina Leen’s iconic 1951 Life magazine photo “The Irascibles” that featured Abstract Expressionist heavyweights Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, and Barnett Newman, Pousette-Dart has always stood on the edges, as he does in the photo, of full identification with that group.

The “X” factor that frees Pousette-Dart from that and other “-isms” is both his ecstatic spirituality and endless artistic exploration stretching across six decades of work. The new Philadelphia Museum of Art exhibition Full Circle: Works on Paper by Richard Pousette-Dart takes aim not at pinning down Pousette-Dart, but rather at targeting his insatiable drive to work through the ideas of modern art on paper by continually building them up before breaking them down again. You’ll think you’re touring a group show before realizing that it all came from one artist’s vision—an ecstatic celebration of Richard Pousette-Dart’s celebration of the making of art itself.

Arranged chronologically, the show begins with drawings from the 1930s tied closely to his and others’ sculpture. Influenced by African, Native American, and Pre-Columbian art as well as by modernists Ezra Pound, John Graham, and Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Pousette-Dart’s early works on paper show the young artist—son of a poet-musician mother and painter-teacher-author father—soaked in multiple sources and synthesized them quickly. More importantly, as Innis Howe Shoemaker, curator of the exhibition, points out in her catalog essay, “From beginning to end,… Pousette-Dart’s enormously varied oeuvre wears its process on its sleeve: the layering and scraping, scribbling and dripping, dotting and blotting.” As impressive as all the influences and responses to them are, the beating heart of Pousette-Dart’s art remains throughout the show this sense of play, of physically working out ideas, which makes this exhibition of his works on paper (65 pieces plus six of his notebooks, many borrowed from the artist’s estate) the perfect medium for that message.

As you move through the exhibition and follow Pousette-Dart’s explorations, you can’t help but sneak peeks backwards and forwards along his timeline. When you move into the 1940s work, similarities to works by Rothko and Pollock become obvious. Shoemaker cautions, however, that “[r]esemblances between the work of Pousette-Dart and that of Pollock are more complex and longer lasting” than they first appear. Graham’s influence links Pousette-Dart and Pollock to a point, but the greater bond comes from their shared sense of experimentation (“parallel paths,” as Shoemaker puts it) given the circumstances of art making at the time.

“As the 1940s progressed,” Shoemaker continues, “the affinities [between them] were evident not so much in the appearance of their work as in their working methods and in their common fascination with testing the fluid borders between drawing and painting.” Both artists broke new ground, but while Pollock rose to fame (and infamy) and died before he could creatively move on, Pousette-Dart enjoyed lesser fame but lived on to go where no Abstract Expressionist, including Pollock, had gone before.

The works themselves demand close scrutiny, practically begging you to get up close to see the scratches and dense layering of Pousette-Dart’s intimate art making. The early sculptural drawings give way to Miro-esque biomorphic figures and geometric designs, which give way to exuberant all-over doodles, but the greatest, wildest, most intense doodles ever. (The notebooks, full of such doodles, are every daydreaming schoolchild’s heaven.) But just as the Pousette-Dart’s color reaches its crescendo, he lowers the volume back to black and white works. “Black and white is the guts of all color,” Pousette-Dart wrote directly above his “extacy” comment. Looking at these black and white works beside the colored pieces, you see how he squeezes every ounce of potential from an artistic opportunity before shaking the great Etch-a-Sketch of his vision and starting from square one, black and white, again, but with all the lessons learned applied to the next build-up.

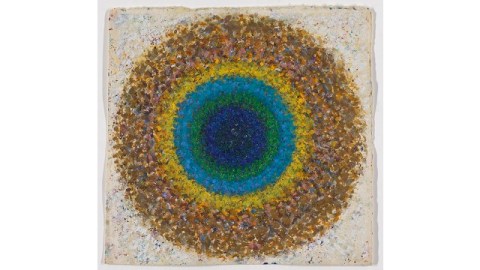

By the 1960s, Pousette-Dart adopted a private brand of pointillism resulting in works such as Center of Remembering (shown above). Pousette-Dart remembers the lessons of Seurat, but also remembers the lessons of his experimentation to add new ideas of line and gesture. The result is what he called “living edges” that both radiate from the cooler colors of the center and oscillate with hotter-colored energy on the periphery. Unsurprisingly, Pousette-Dart moved on from these edgier works back to the beginnings of black and white, pencil on paper.

Unfortunately, just as Pousette-Dart’s experimentation is his triumph, it’s also his tragic flaw, at least in the eyes of taste-making critics of his time. Shoemaker points out that Pousette-Dart’s “practice of simultaneously producing stylistically separate bodies of work… confused critics and left them feeling compelled to judge which style was more successful.” Faced with too many choices, critics sometimes chose none of the above, denying Pousette-Dart the status more single-minded stylists such as Pollock achieved. “[B]eware of all schools, isms, creeds, or entanglements,” Pousette-Dart warned young artists in a 1951 lecture, advice he himself adopted as a personal credo. The truly creative mind is a restless, unentangled mind for Pousette-Dart. Art history appreciates neat linear progressions and Picasso-esque periods to categorize, but Pousette-Dart reminds us of the messier, more interesting reality. Instead of a straight line, Pousette-Dart gives us a circle (perhaps his favorite motif)—a recursive process without end that continually grows as it returns to the beginnings with greater and greater knowledge and skill. “Circles are/ whatever you make them,” Pousette-Dart wrote in another notebook, “all or nothing.” For Pousette-Dart, the circular process was all.

When composer and musician Duke Ellington gave his highest praise, he used two simple words: “Beyond Category.” Ellington hated ghettoizing, limiting terms such as “Jazz” as much as Pousette-Dart resisted the entangling terms of his own art form. Full Circle: Works on Paper by Richard Pousette-Dart, which runs through November 30, 2014, proves that being “beyond category” is no sin, but rather a saving grace. Like The Jewish Museum’s current exhibition of marginalized Abstract Expressionist artists Lee Krasner (“Mrs. Jackson Pollock”) and African-American Norman Lewis and twoseparate New York City exhibitions of Helen Frankenthaler and Morris Louis (the best of the Color Field school, Clement Greenberg’s kinder, gentler, and perhaps feminized sequel to Abstract Expressionism), this exhibition reclaims a lost member of the AbEx generation to show the more complicated and more diverse reality unfairly shouldered aside by the standard, Pollock—de Kooning two-headed monster. Full Circle might not be the exhibition for those who want their art in tidy categories, but for those open to enjoying art directly, without filters or barriers, it might just inspire you to pick up a pencil yourself and start drawing.

[Image: Center of Remembering, 1960s. Richard Pousette-Dart, American, 1916-1992. Oil paint over opaque watercolor, with glitter paint on wove paper, Sheet: 11 5/16 × 11 7/8 inches (28.7 × 30.2 cm). Philadelphia Museum of Art, © 2014 Estate of Richard Pousette-Dart / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.]

[Many thanks to the Philadelphia Museum of Art for providing me with a press pass to view as well as a review copy of the catalog to the exhibition Full Circle: Works on Paper by Richard Pousette-Dart, which runs through November 30, 2014.]