Roz Chast’s Comic Take on Taking Care of Elderly Parents

“It was against my parents’ principles to talk about death,” Roz Chast writes in Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?: A Memoir. “Between their one-bad-thing-after-another lives and the Depression, World War II, and the Holocaust, in which they both lost family—it was amazing that they weren’t crazier than they were. Who could blame them for not wanting to talk about death?” In this, her first memoir, Chast talks and cartoons about death years after her parents’ deaths and the trip down that long road to that end, which starts slowly in her childhood but accelerates frenetically in those final years of emotional and physical dependence. Many of us will face the unavoidable realities surrounding aging and dying parents, but Chast’s Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?: A Memoir offers, if not advice, at least sympathy from one who’s been there and survived with wit and compassion.

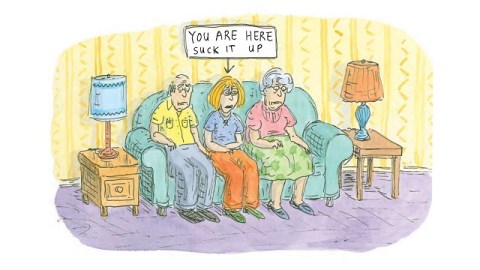

Chast is best known for her cartoons for The New Yorker, for whom she has done over 800 works since 1978. Classic Chast consists of simply drawn figures filled with visible angst, usually against simple backgrounds such as a sofa and patterned wallpaper. Form follows function in Chast’s art, as her expressive lines convey the frenzied state of mind of her characters while her hand-printed text feels like a personalized note just to you. That formula’s worked well for Chast in short-form comics, but it works even better as a unifying (and edifying) force in this long-form meditation on the unpleasant things alluded to by her book’s title.

George Chast, Roz’s father, alternatively leaned upon and cowered under the larger-than-life persona of his wife Elizabeth, an assistant principle whose famous “blast from Chast” ruled over school and home. With heartbreaking detail and honesty, Roz recounts how she grew up as her father’s daughter, sharing the high school French teacher’s love of language as well as his non-stop neuroses, while simultaneously fearing her distant and demanding mother. A serious fall by the aged Elizabeth sidelines her and forces Roz to take care of her helpless father, whose Alzheimer’s disease is much further along than she had realized. Anyone who’s dealt with someone suffering from Alzheimer’s will recognize the frustrations and inadvertent comedy Chast captures. The indomitable Elizabeth eventually rallies, but their situation worsens to the point that Roz must move them out of the Brooklyn apartment of her childhood (“which was dark and shabby and smelled like the end of the world”) to a retirement home (decorated in “Old-Person-Cheerful-Genteel”) nearer to her Connecticut home. A simple panel of Chast’s parents rolling luggage behind them down the hall as they leave their apartment for the last time will pull on your heartstrings with pathos.

Chast then faces the herculean task of clearing out her parents’ apartment and deciding what memories to save and which to leave to “the super” and, presumably, the dumpster. Musing upon that editing of their lives, Roz says philosophically, “Once you go through that, you can never look at your stuff in the same way. You start to look at your stuff a little… postmortemistically.” Thus, dealing with her parents’ decline and approaching deaths raises questions about her life and how her own children will eventually face the same challenges. I enjoyed and appreciated Chast’s clear-eyed, comic view of end-of-life issues such as finances and selecting care options, especially when your parents can still “see through the euphemisms.” Cartoons about the alternating boredom and anxiety of endless paperwork, the momentary self-congratulatory crowning as the “perfect” daughter, and the eventual acceptance of being “gallant and goofus” in dealing with it all might easily serve as an appendix to the Kübler-Ross model of the stages of grief for those dealing with all the unconsidered stages ranging from health care costs to unresolved mommy issues.

At its heart, Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?: A Memoir is a tale of two closets: the “crazy closet” of the Brooklyn apartment that housed everything from a “museum of old Schick shavers” to her mother’s handbag collection and the closet in Chast’s home today where the cremains of her father, who died in 2007, and her mother, who died in 2009, reside. Chast once remarked that her cartoons were about the “conspiracy of inanimate objects,” an idea originating from her mother. We are what we hoard, Chast suggests, right down to our physical bodies, our final possession. Just as the “crazy closet” stands for her parents’ (perhaps) justifiable insanity during her childhood, Chast’s current closet and those cremains stand for their lingering presence in her imagination and art—both the paternal tenderness and the maternal sarcasm that fuel her work.

Near the end of Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?: A Memoir, Chast includes a series of drawings of her mother when Elizabeth silently persisted “in a state of suspended animation… not living and not dying.” Roz’s sketches of her sleeping mother resisting death reminded me of the old, pre-photography practice of taking life and death masks of wax or plaster. Whereas life masks taken from living subjects revealed what they looked like while conscious, many argued that death masks—taken when the facial features softened and relaxed—revealed a truer self, freed of defenses. Chast’s sketches fall somewhere in between, catching her mother’s struggle to hold on to her defiance of death itself despite the pull to accept powers larger than the self. Likewise, Roz Chast’s Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?: A Memoir pulls you in different directions—laughing at the quirks of every family, nodding at the financial black hole of the American way of dying, and considering our own eventual end and the continuation of the cycle for our children. But as much as Chast pulls you in all those directions, after reading her memoir you feel just a little more confident that dealing with these things less pleasant won’t pull you apart.

[Image:Roz Chast. From Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?: A Memoir.]

[Many thanks to Bloomsbury Press for providing me with the image above from and a review copy of Roz Chast’s Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?: A Memoir]