Richard Hamilton: The True King of Pop?

Michael Jackson proudly wore the crown as the “King of Pop” until his death in 2009. In the visual arts, at least for Americans, Andy Warhol’s ruled as the “King of Pop,” reigning as the prime example of Pop Art for the uninitiated as well as for connoisseurs. Most British (and more than a few American) art lovers, however, see Richard Hamilton as the true “King of Pop” and Warhol as just an upstart usurper to the throne. The Tate Modern’s new exhibition Richard Hamilton, which runs through May 26, 2014, provides not only a survey of Hamilton’s greatest pop hits, but also a career-long survey that shows how he engaged with popular culture beyond just Warhol-esque celebrity and marketing gestures and got at the heart of what Pop Art should and could be. Is Richard Hamilton the true “King of Pop”?

The first and perhaps most compelling argument in Hamilton’s favor is that he’s the father of Pop Art. Hamilton’s 1956 collage Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing? might be the first Pop Art piece, if you discount all the proto-Popsters such as Marcel Duchamp and Kurt Schwitters. In fact, it’s not until the early 1960s, when Hamilton comes to the United States to curate a show of Duchamp’s work that he meets Warhol, Roy Lichtenstein, and other American Pop Artists and they begin to work in a Pop Art style. So, you might call Hamilton the father of both British and American Pop Art. In addition to encouraging American artists, Hamilton helped David Hockney and Peter Blake at the beginnings of their Pop-ish careers. Combine Hamilton’s forward looking eye for new talent along with his commitment to teaching the public about Duchamp and Schwitters (going so far as to save Schwitters’ Merzbarn from destruction by neglect) and he’s not just a branch on the Pop Art tree—he’s the life-sustaining trunk!

As much as Warhol ingratiated himself with the world of celebrity in the 1960s and 1970s, there was always the complication of Warhol’s paradoxical introspective nature—an exhibitionist who hid behind glasses and wigs to the point that the “Andy” we “knew” wasn’t the Andy underneath, whomever that might have been. Richard Hamilton, on the other hand, swung hard with the “Swinging London” of the Sixties. How many artists can claim to know both The Beatles and The Rolling Stones at the height of their fame? Hamilton’s friendship with Paul McCartney led to the cover design (or lack of) and name of The Beatles’ White Album. Through his dealer and friend Robert Fraser (aka, “Groovy Bob” and, possibly, “Dr. Robert”), Hamilton dove deep into the spirit of the age and lived in (rather than emptily symbolized, a la Warhol) the pop culture he put into his art.

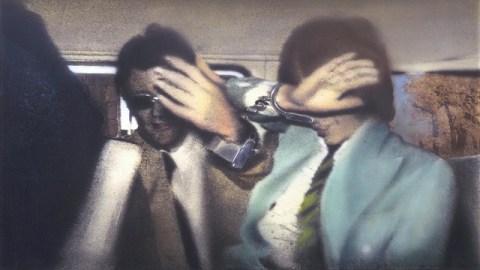

Aside from his engagement with the celebrities of the time, Hamilton engaged with the politics of the time in a way that neither Warhol nor most other Pop Artists did or even dared. Whereas Warhol could create a politically neutral portrait of even Mao (more drag queen than malevolent dictator), Hamilton could strike a political note even when documenting a seemingly purely pop culture moment. In Swingeing London 67 (f) (detail shown above; from 1968-1969), Hamilton appropriated a newspaper photo of his friend “Groovy Bob” Fraser and Rolling Stones’ frontman Mick Jagger in the back of a car raising their shackled hands to cover their faces from the press coverage of their drug arrest as part of the raid on Rolling Stones’ guitarist Keith Richards’ Redlands home. In addition to creating a collage of press clippings of the incident, Hamilton focused in on this one image, adding pastel-like colors to create a dreamy, almost fantasy version of the very serious charges. Jagger and Richards were acquitted on appeal, but Fraser pled guilty to heroin possession and received the severe or “Swingeing” sentence of 6 months of hard labor. Rather than a typo or a British spelling, the swap of “Swingeing” for “Swinging” emphasizes the severity of Fraser’s sentence, which only led to harder substance abuse by Fraser and the eventual loss of his gallery. What looks like a fun, breezy moment becomes a politically charged image in which the culture clash took a casualty close to Hamilton himself. In retrospect, Swingeing London’s an elegy for the “Swinging London” coming to an end as the Sixties and the Sixties’ spirit began to disappear.

But, at least for me, the thing that makes Hamilton the ultimate Pop Artist is that he never lost touch with the times even as they changed around him. Warhol always seems somehow trapped in the amber of the Sixties and Seventies, a relic as dated as an eight track. Hamilton, however, even well into his eighties, could play the rebel. In 2008, Hamilton collaborated with members of the University for West England to create “a medal of dishonor” titled The Hutton Award that featured the face of former British Prime Minister Tony Blair on one side and Blair’s Rove-ian “Spin Doctor” Alastair Campbell on the other. This new show at the Tate Modern is the first ever full career retrospective of Hamilton, who died in 2011. Stretching across six decades, the show brings together Hamilton’s most famous works not just in painting and photography, but also in design, film, and collaborations with others, such as The Hutton Award. Part of what made Warhol popular and acceptable was his broad appeal—not too political, never controversial aside from the initial “shock” of Pop Art. But what makes Hamilton important, as the exhibition Richard Hamiltonmore than demonstrates, is his continual willingness not just to take from popular culture, but also to give back, to use the fragments of contemporary life to piece together some sort of meaning and demonstrate that Pop Art wasn’t just shorthand for popular art, but also the art of the populace.

[Image:Richard Hamilton. Swingeing London 67 (f) (detail), 1968-9. Acrylic, collage and aluminium on canvas. Support: 673 x 851 mm. Frame: 848 x 1030 x 100 mm. Tate. Purchased 1969. © The estate of Richard Hamilton.]

[Many thanks to the Tate Modern, London, UK, for providing me with the image above and other press materials related to the exhibition Richard Hamilton, which runs through May 26, 2014.]