Picturing the Fourth of July

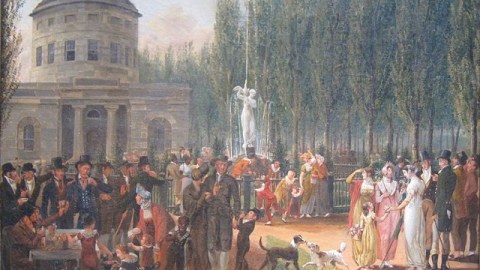

Americans for the past decade seem more caught up than ever in the idea of what it is to be an American, especially in an election year and perhaps never so much as on the Fourth of July—the day on which we celebrate the Declaration of Independence that inaugurated this little experiment in democracy we’ve been performing for over two centuries. To see a picture of the Fourth of July 2012, all you need to do is look out your window at the parades, barbeques, and fireworks. But to look back two centuries and see the Fourth of July circa 1812, perhaps our best glimpse appears in John Lewis Krimmel’s Fourth of July, Center Square (detail shown above). Krimmel’s genre scene of Americans celebrating America back then allows us to see how our celebration today mirrors and, perhaps, distorts what our ancestors saw as most important for our country.

An immigrant from Germany at the age of 13, Krimmel became one of the first important genre painters in America. A fan of both Benjamin West and William Hogarth, Krimmel painted real life, but also injected allegory into his works. Krimmel’s European eyes must have marveled at the sight of the freshly woven tapestry of democracy straining to hold itself together in the shape of the young United States of America. Working in Philadelphia, Krimmel painted the free African-Americans who walked the streets after their liberation from Southern slavery. Two quintessential American days especially held his interest—Election Day and the Fourth of July.

In Fourth of July, Center Square, Krimmel paints the whole spectrum of Philadelphia society at the time: plainly dressed Quakers stand to the left, more fashionably dressed affluent citizens cluster to the right, and middle classes muddle in the middle, naturally. The tableau of American classes stretches across the canvas like a classical frieze, with Benjamin Latrobe’s Greek Revival style Pump House, part of the Fairmount Water Works, presiding in the rear like the ghost of Greek Democracy itself. Closer to the ground, William Rush’s wooden sculpture, Water Nymph and Bittern, stands at the center of the first public fountain in America. Yellow Fever ravaged Philadelphia in 1793. Because many believed that Yellow Fever traveled via foul water, Philadelphia united to build a water treatment plant to combat the yellow peril. Krimmel picked this particular place at this particular time as a perfect emblem for a celebration of government of the people, by the people, and for the people. Although European class differences remained residually in the early 19th century, a greater egalitarianism was on the rise, as shown by the mingling of the different groups all in one American moment.

A lot has been made this year of the sesquicentennial of 1862 and that year’s events of the Civil War, but not as much noise has been made over the bicentennial of the War of 1812, which gave us our national anthem, “The Star-Spangled Banner,” thanks to Francis Scott Key’s musing over the Battle of Fort McHenry in September 1814. Without the Battle of New Orleans (the last major fight of the war, which actually took place after the signing of the Treaty of Ghent that ended the war), General Andrew Jackson might never have given us Jacksonian Democracy as President Jackson. But perhaps the most lasting legacy of the War of 1812 was the Burning of Washington, DC, by the British in 1814, including the White House and U.S. Capitol. August 24, 1814 was for that generation celebrating above two years earlier what 9-11 was for us in terms of symbolic loss. But they survived, and flourished.

For me, the War of 1812 is the ultimate “forgotten war,” overshadowed on one side by the American Revolutionary War and on the other by the Civil War, our “second” revolution. Even the Mexican-American War, caught in the same shadows, isn’t as fraught with implications. Sadly, we have too many “forgotten wars”: the Korean War (crushed between the giant emotional weights of World War II and the Vietnam War); the Spanish-American War (we “Remember the Maine,” but nothing else); and our current memory lapses over the War in Afghanistan and the War in Iraq (catch Rachel Maddow’s Drift: The Unmooring of American Military Power for interesting insights into how we forget something that literally happened yesterday). Looking at Krimmel’s Fourth of July painting, I almost imagine these people coming together during the conflict so soon after and realizing that their young society was worth saving. That common cause seems to be something we’ve forgotten in our polarized, politicized state.

Sadly, Krimmel drowned in 1821 at the age of 35, just as he was gaining prominence in the American art world. It would have been interesting to see what he would have painted during the Civil War, that pinnacle both of disunion and reunion. I’d love even more to have him look at today and paint what he sees. Would he paint a 1812-esque tableau of diversity coming together? What would be the grand civic projects for the people to rally about? On this Fourth of July 2012, do we look back on the celebrants of 1812 in envy?

[Image:John Lewis Krimmel. Fourth of July, Center Square (detail), 1811-1812.]