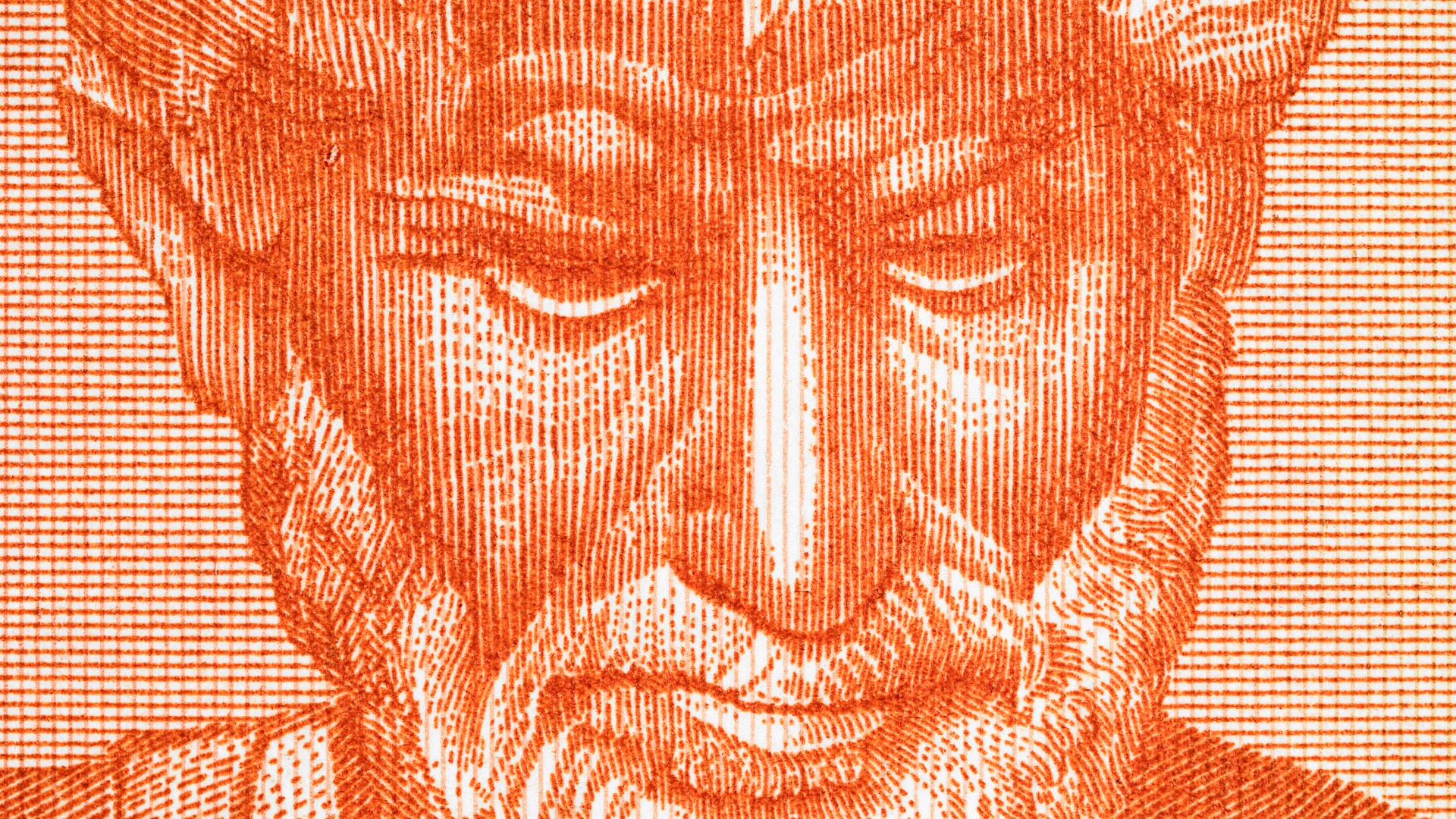

Is This the End of Damien Hirst?

When news came out recently that artist Damien Hirst had ended his long and lucrative relationship with dealer Larry Gagosian and his international chain of Gagosian Galleries, there was more than a presumptive little dancing on the grave of Hirst’s career. It seemed that the man famous for his formaldehyded shark (in 1991’s The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, shown above) was now chum in the art world waters. Esquire’s Stephen Marche not only announced the end of Damien Hirst, but also “the end of art as pure money.” But before we call in the undertakers, let’s undertake an analysis of whether this really is the end of Damien Hirst and the era of “art as pure money” he embodied.

Just last year, Hirst seemed to be on top of the art world. Hirst’s first major museum retrospective at the Tate Modern, timed to coincide with exhibits of his spot paintings the at 11 Gagosian-owned galleries around the globe, hinted that Hirst might finally break the glass ceiling of contemporary art and join the ranks of the “Old Masters” (and command “Old Master” money). Even his own studio webcam to show the artist at work, or rather the artists who did the work Hirst conceptualized, threatened to offer 24-7 Damien. And when you raise the ire of an acknowledged artist such as David Hockney, you know you’re either doing something right or something terribly, terribly wrong. All these signs and more pointed towards bigger and better things for Hirst.

Looking back now, however, they all look like a final, desperate push for acceptance and the monetary success that had eluded Hirst since the financial fiasco of For the Love of God, the diamond encrusted skull whose “sale” (or no sale) revealed the first chink in Hirst’s armor. The original YBA, or Young British Artist, part of the group that dominated the 1990s art scene with a punk rock sensibility coupled with a Wall Street lust for money, Hirst now seems as dated as the clothing and music of that time. “The [Hirst-Gagosian] breakup comes at the end of a sharp, sudden, virtually unprecedented decline of Hirst’s career and represents something of a turning point for art, and possibly for culture more broadly,” Marche concludes. “It’s the end of the era of pure money.”

Marche links Hirst’s fall with the 2008 global financial crisis. Just as people lost faith in the banking system, people lost faith in Hirst. The emperor no longer wore the posh clothes of the art world elite. Hirst’s kitschy spot paintings stood naked for what they were—unashamedly naked appeals for art prices based solely on name recognition, with not creative capital to back it up. Marche qualifies his claims by adding that “[t]he collapse of Hirst’s career is not a sign of the end of money in art, of course. Money and art will always be intertwined.” Instead, “Hirst’s breakup with Gagosian does signify the end of a kind of obsession that saw nothing other than money.” With Hirst’s fall comes “the return of messiness and humanism and a struggle beyond the gallery walls,” Marche concludes hopefully. “The navel gaze has swallowed itself. Art will have to be about something larger than its own value or go bankrupt.”

The optimist and idealist in me want to agree with Marche. I believe that the best art is always about more than just art itself. Duchamp started modern art on a revitalizing, self-analyzing path that has become in many ways a confounding Mobius strip. Art in many ways has been walking a road to nowhere, led by people like Hirst, who have been abetted by Gagosian and others subsidizing the trip. I doubt that we’ve heard the last of Damien Hirst, since we probably haven’t even heard the first of the next “Damien Hirst.” But at least, as Marche writes, “the navel gaze has swallowed itself.” Instead of Hirst’s neat, mindless dots, let “messiness and humanism” show us why and how art matters.

[Image:Damien Hirst.The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, 1991.]