Illuminating Walt Whitman’s Words with Pictures

It’s one of the great openings in all of American literature: “I celebrate myself, / And what I assume you shall assume, / For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.” So begins Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” the opening and central poem of Whitman’s life’s work, Leaves of Grass. Generations of readers—many enthralled, but many confused—have encountered the “Good Gray Poet” in classrooms, but Whitman’s the poet of wide open spaces from the wilderness to the cosmos. Allen Crawford’s new illustrated version of “Song of Myself,” titled Whitman Illuminated: Song of Myself, hopes to bring clarity to those struggling with the poem in the belief that “every atom belonging to” Whitman “as good” still remains to us, if only we can crack the poet’s code and rediscover the good he recognized in everyone through his fervent spiritual, poetic, and democratic ideals.

Crawford, co-proprietor of the design/illustration studio Plankton Art Co. with Susan Crawford, his wife, admits to a deeply personal connection to Whitman. Living just outside of Philadelphia, in the area where Whitman spent the last decades of his life, Crawford’s not only enjoyed the same natural wonders Whitman wrote about, but also has “visited his Mickle Street house in Camden many times, and [has] stood in his bedroom, where his metal washtub is tucked under his heavy wooden bed.” That physical connection extended to the “trove of materials and personal effects for local archivists and historians to sift through,” Crawford writes. “To hold, feel, and study Whitman’s books and letters first-hand enriched the endeavor of giving his work a new incarnation.” Crawford stresses throughout his introduction that his work isn’t a slavish, line-by-line, literal interpretation of Whitman’s words into images. “With this book, I’ve tried to make the vigor of ‘Song of Myself’ tangible,” Crawford explains. “I’ve attempted to liberate the words from their blocks of verse, and allow the lines to flow freely about the page, like a stream or a bustling city crowd.” Each of the 117 two-page spreads (which each took 8 to 10 hours to complete, adding up to an estimated 2,560 hours total) features text from the poem sprawling across in the page in a variety of hand-drawn fonts accompanied by whatever image the words inspired Crawford to draw. “The book was improvised, not planned,” Crawford says. “My goal was to leave an interpretive gap for the reader—or should I say viewer—between the poem and my responses.” Just as Whitman left an open invitation—not a command—to his reader to follow, Crawford invites you into Whitman’s (and his) world by leaving some of the imaginative work for you.

In those interpretive gaps await all the fun. A literal-minded illustrator might accompany that classic opening with a standard portrait of Whitman, either as the elder shaman he’s remembered best today or perhaps as the younger, open-collared, head-defiantly-tilted version that appeared facing the title page of the 1855 edition (the text that Crawford uses in favor of later, less spontaneous editions). Although Whitman continues his opening, “I loafe and invite my soul, / I lean and loafe at my ease . . . . observing a spear of summer grass,” Crawford doesn’t loaf around creatively, choosing instead to give us an animal-human hybrid Whitman with a human face but antlers, a lion’s body, and wings. This Whitman as griffin is totally unexpected, but unexpectedly perfect in capturing Whitman’s mythological self-fashioning linked to the primal in nature and humanity. In just that single two-page illustration, Crawford crows that this is no conventional illustrated book, just as Whitman—regardless of the barnacles of familiarity that have attached themselves to his reputation over the years—was and still is no conventional writer.

Similar surreal images challenge the reader’s imagination throughout: a hairy, yeti-like pensively ponders a skull, a la Hamlet; a stream of disembodied eyeballs roll across two pages in a possible allusion to the “transparent eyeball” of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Whitman’s hero; a bearded man walks on his hands and feet shod with an assortment of footwear, including a high heel, a work boot, a sneaker, and a loafer (the better to “loafe” with, perhaps). But Crawford really illuminates Whitman’s focus on nature when he employs his considerable skill as an artist of nature. Allen and Susan Crawford’s most notable project is a collection of 400 species identification illustrations (so far) on permanent display at the American Museum of Natural History’s Milstein Hall of Ocean Life. So much of getting Whitman involves following him down to an almost microscopic level to reach the macrocosmic level he’s really writing about. Crawford’s naturalistic images live up to the title’s illuminating promise by allowing us to really see the minutiae in which Whitman witnessed the majestic.

Part of Crawford’s illuminating project includes not as much an updating of Whitman but a reminder of his enduring relevance. When we get to Whitman announcing “I am the poet of the body, and I am the poet of the soul,” Crawford gives us an astronaut floating in space at the end of an umbilical-like tether. Leaves of Grass was the first American space program, Crawford reminds us, later making it even more obvious as he has Whitman skip from planet to planet out of our solar system. When Whitman praises “the sounds of the city,” Crawford gives us two urban basketball players, with one only half seen as he soars to the basket. If Whitman were alive today, I’d imagine him loving the flow and freedom of the city game, probably courtside at the Knicks beside Spike Lee. When Whitman speaks of a “performer” of “loose-fingered chords,” Crawford sits us down in an old-style diner booth with mini-jukebox on the table. Crawford defends these anachronistic images of life today by explaining that “[n]ot doing so would have been a disservice to Whitman’s work, which attempts to create a new form of verse for the The Here and The Now.” Whitman Illuminated illuminates Whitman for “The Here and The Now,” because anything less would be pointless, un-Whitman-esque.

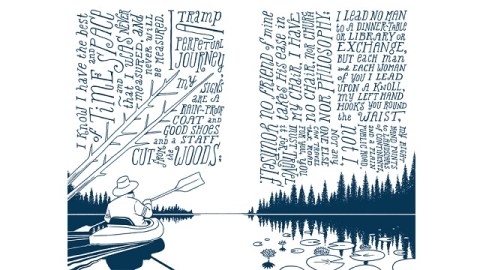

“I tramp a perpetual journey,” Whitman writes late in “Song of Myself.” “My signs are a rain-proof coat and good shoes and a staff cut from the woods.” Crawford chooses a simple image of Whitman rowing down a waterway between tree-covered banks—a metaphor for the perpetual, flowing, ever-changing-but-never-changing-like-a-river mind trip we all find ourselves taking. This image reminded me of Crawford’s telling us in his introduction that he’s “kayaked in the cove behind Petty’s Island on the Delaware River, where Whitman would picnic on weekends with his friend and amanuensis, Horace Traubel.” Allen Crawford’s Whitman Illuminated: Song of Myself proves that he’s walked in Whitman’s footsteps and rowed in his wake physically and creatively. More than just a copyist or amanuensis, Crawford emerges as a true companion of Whitman, a fellow traveler on the cosmic river to enlightenment who uses his skills to bring Whitman to a new generation in his fullest sense. Perhaps too creative and imaginative for those unfamiliar with Whitman, Whitman Illuminated: Song of Myself will take those who have stumbled those first few steps with the sage and light the way much further down the road both to the poet and to a fuller understanding of themselves.

[Image: From Whitman Illuminated: Song of Myself, illustrated by Allen Crawford.]

[Many thanks to Tin House Books for the image above and a review copy of Whitman Illuminated: Song of Myself, illustrated by Allen Crawford.]