How to Take Ai Weiwei With You Wherever You Go

During the height of the Cultural Revolution in China, leader Mao Zedong wanted his thoughts spread to every corner of the country. Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung (aka, “The Little Red Book”) found its way into the pockets and consciousness of every Chinese citizen. Mao’s oppressive, all-controlling vision continues to overshadow Chinese life, but a new pocket-sized book hopes to shine a light in the midst of the darkness. Ai Weiwei’s Weiwei-isms (edited by Larry Warsh and published by Princeton University Press) aims to spread Ai Weiwei’s ideas of freedom and expression across not just China, but the world, by collecting the artist’s best bon mots from interviews, articles, and even tweets. “But censorship by itself doesn’t work,” the artist says of the Chinese government’s many efforts to silence him. “It is, as Mao said, about the pen and the gun.” In turning the memory of Mao around in a positive direction, Ai Weiwei makes it once more “about the pen and the gun,” but mixes in the unforeseen, excitingly uncontrollable element of social media.

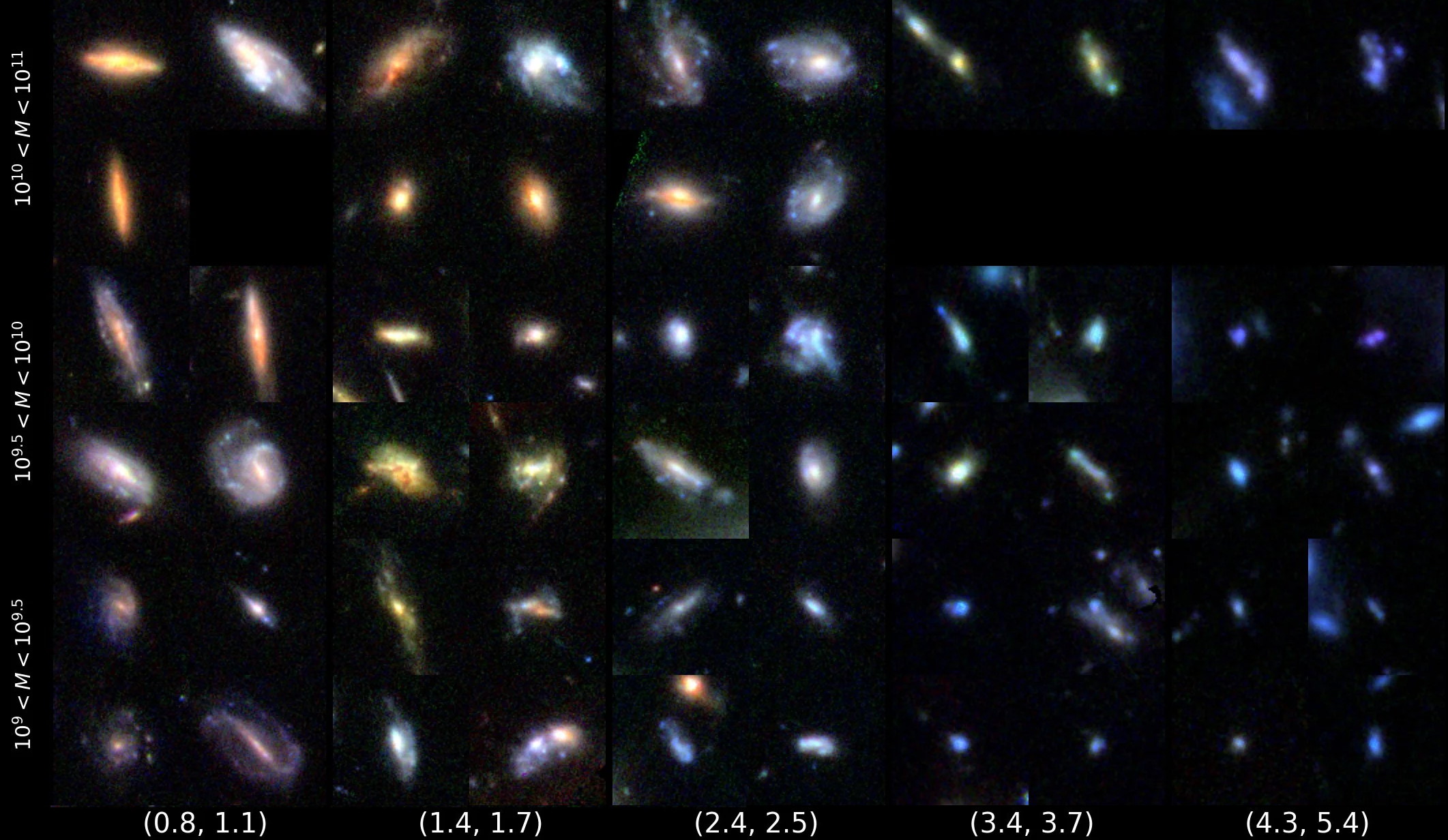

“Weiwei-isms distills Ai Weiwei’s thinking on the topics of individual rights and freedom of expression,” Larry Warsh and J. Richard Allen write in the introduction, “filtered through his responses to a range of events—the 2008 Beijing Olympics and Sichuan earthquake, for instance, or his own eighty-one-day detention by Chinese authorities.” (A helpful chronology of events in the back of the book will get those who haven’t been following Ai Weiwei’s story up to speed.) “Ai Weiwei brandishes the written word to expose the enormous chasm between the [Chinese] government’s use of language and its authoritarian actions,” the introduction continues. In this literal “war of worlds,” Ai Weiwei fires short bursts of language like verbal “bullets” of resistance.

Reaching back past Mao’s pithy passages to the Chinese tradition of Confucius’ philosophical sayings, the artist also embraces the modern world of 140-character pronouncements on Twitter. In the section marked “On the Digital World” (one of six sections the editor uses to organize the quotes), Ai Weiwei calls Mao “the first in the world to use Twitter,” muses on how concise Confucius could have written whole novels in a single tweet, and states that Shakespeare, were he alive today, would definitely be on Twitter. “Twitter is the people’s tool,” Ai Weiwei believes, “the tool of the ordinary people, people who have no other resources.” Whereas Samuel Johnson once said that false “Patriotism is the last refuge of the scoundrel,” Ai Weiwei says that today the last refuge of a true patriot, a true lover of the people, is social media.

But where does Ai Weiwei the artist fit into all of these politics? “Everything is art,” he responds. “Everything is politics.” In addition to being a guide on how to live life, Weiwei-isms works as a guide on how to make art. “We see plenty of artistic work that reflects superficial social conditions, but very little work that questions fundamental values,” he complains. Ai Weiwei defines being a modern artist as “a symbolic thing,” ala Marcel Duchamp. “After Duchamp,” he writes, “I realized that being an artist is more about a lifestyle and an attitude than producing some product.” Ai Weiwei, however, denies that his actions comprise some elaborate “performance art”: “It’s really life and death [not art].” All life is art, so how can you categorize any part of it as a “performance”? Ai Weiwei sounds the most Duchampian when he says that “[t]radition is only a readymade. It’s for us to make a new gesture—to use it as a reference, more as a starting point than conclusion,” hence the paradoxes of a modern artist channeling Confucius and a series of Tweets and online writings converted into old school, dead tree books. Life, art, and politics are all what you make of them—starting points in a race to serve the human race.

If it’s even possible to put a whole person into your pocket, Weiwei-isms comes close. Of course, Ai Weiwei himself contains multitudes, but the editors perform yeoman work in encapsulating the essence of the man and his mission. Despite the deadly seriousness of the task at hand, they never lose touch with the fun and humor at the heart of who Ai Weiwei is. “Measuring national prestige by gold medals is like using Viagra to judge the potency of a man,” Ai Weiwei writes in a jab at the Chinese government’s obsession with the 2008 Beijing Olympics. While reading Weiwei-isms I couldn’t get out of my head the image of the artist himself peeking over the pages (perhaps as shown above), Cheshire cat grin hidden but undeniably in place. Weiwei-isms will have you grinning, and thinking, and, Ai Weiwei hopes, acting. “My favorite word?” he asks. “It’s ‘act.’” Unlike “The Little Red Book,” carrying Weiwei-isms isn’t compulsory, but you’ll find yourself compelled to read it again and again and fit it into your head and heart, if not your pocket.

[Many thanks to Princeton University Press for the image above and for a review copy of Weiwei-isms by Ai Weiwei and edited by Larry Warsh.]