Does Cultural Big Data Amplify the Anxiety of Influence?

The only thing possibly worse than facing a creative blank is facing a creative overload—to find yourself drowning in a sea of influences with no guiding life preserver in sight. In a recent article in Wired, Paul Ford wrote about how “Netflix and Google Books Are Blurring the Line Between Past and Present” and creating what he calls “a history glut.” Although Ford focuses primarily on the “history glut” and delves momentarily into the “music history glut,” similar gluts can be seen in all the arts, especially the visual arts. Literary critic Harold Bloom coined the phrase “the anxiety of influence” in 1973 with no clue how that anxiety would blossom exponentially four decades later. Can artists today cope with that growing, digitally available anxiety to create their own art? Does cultural big data amplify the anxiety of influence?

“It used to be that, for economic and technological reasons, this cultural history was locked away,” Ford writes. Whereas most archival data was unavailable to the masses before, a “reversal has happened in just the past decade. We are now living in a history glut; the Internet has muddled the line between past and present.” Netflix, Google Books, YouTube, and a host of other options leave us “in an online realm where the old is just as easy to consume as the new,” Ford believes. “We’re approaching an odd sort of asymptote, as our past gets closer and closer to the present and the line separating our now from our then dissolves.” Ford cites as an example the recent 50th anniversary of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy marked by CBS’ streaming of 4 days of news broadcasts from the time to recreate how events unfolded back then in what would feel like real time now. Such a treasure trove of material feels like a blessing, until it feels like a curse.

“Perhaps the biggest result of the history glut is that managing all that history becomes the crucial act, both commercially and intellectually,” Ford concludes. While we’re spending time and energy dealing with all this data, we’re failing to create ourselves. “There’s an irony here: All of the data we’re collecting, all of the data points and metadata, is history itself. Much as we marvel at Babylonian clay tablets listing measures of grain, future generations will find just as much meaning in our log files as they will in the media we consume,” Ford argues. The history we’re doomed to leave behind for future generations becomes our browser histories, which Ford thinks “will be the defining historical objects of our era.” Do we really want future generations to ponder our YouTube preferences like the 6th century BCE Cyrus Cylinder, an object some believe to document the first statement of human rights? Don’t they have a right to expect more, assuming that they’d even care or would even be able to climb from under the ever-growing mountain of metadata to notice?

Art’s always been about coming to grips with the past, whether to build upon it or bring it crashing down. As Picasso said, “To me there is no past or future in art. The art of the great painters who lived in other times is not an art of the past; perhaps it is more alive today than it ever was.” Before Netflix or Google Books, artists were blurring the line between past and present in their imagination and their art. I’ve always believed that knowing who influenced an artist (positively or negatively) is one of the keys to understanding what they wanted to achieve. Of course, in the past, the possible influences on an artist were limited by opportunity dictated by time, place, education, status, race, and other factors. But with the great democratizer of the internet, the playing field of influence is both leveled and kicked up a notch.

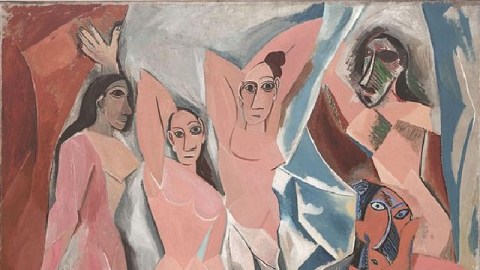

During Picasso’s “African period” of 1906 through 1909, as Cubism queued up in his long list of styles, Picasso could appreciate African art in museums and even collect items on the burgeoning African art market at a manageable pace. If Picasso were to begin his exploration of African art today starting with a Google search, he’d find approximately 655 million places to satisfy his curiosity. Would we have 1907’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (detail shown above), the greatest masterpiece of that moment in Picasso’s development, if he spent more time and energy on dealing with the analysis of the influence of African tribal masks than on assimilating and creating from that influence? Is art suffering from a “history glut” threatening to overwhelm artists with influence at the expense of stifling creativity? When contemporary art seems to have run out of ideas, is the real problem that it’s come up with so many ideas that it finds itself paralyzed? Perhaps art history-infatuated artists (and all of us addicted to the vast bounty of the internet) need to learn to tune out sometimes to tune in to themselves. As much as I want to see and experience everything art history has to offer, the law of diminishing returns—a law enforced ruthlessly by big data everywhere—proves that less can, indeed, be more.

[Image:Pablo Picasso.Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (detail), 1907.Image source.]