Can We Finally Take Keith Haring Out of His Time Capsule?

At the Brooklyn Museum’s current retrospective of Keith Haring’s early work, titled Keith Haring: 1978–1982, you can view what may be the earliest video of the artist at work. In Haring Paints Himself into a Corner, Haring literally paints himself into a corner as music by the cult band Devo blares in the background. Friend and fellow artist Kenny Scharf remembers seeing the film being made and Haring painting lines “to the beat of the music, almost like a dance.” It sounds almost like an artsy version of That ‘70s Show, complete with period soundtrack. But, as Jade Dellinger has remarked, Devo’s first album, Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo!, “became a rallying call and a conduit for the like-minded to meet” in that year of 1978. Haring is so much a part of his time and, because of his advocacy and death, the frightened, confused, early AIDS era, the temptation to take him out of the time capsule and gently return him is often irresistible. By looking at the early Haring, however, Keith Haring: 1978–1982 shows how the artist and his spirit live on today.

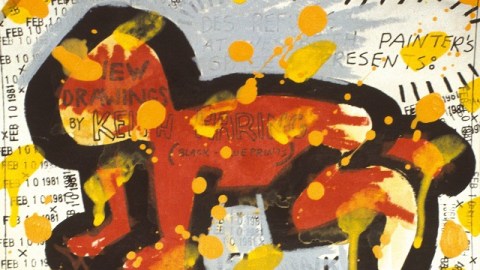

However, there is a kind of holy relic feel to much of the show, which features over 150 archival objects, including rarely seen sketchbooks, journals, exhibition flyers (such as the one shown above), posters, subway drawings, and photographs documenting Haring and friends in action at dance clubs and gallery openings. Haring moved to New York City in 1978, at the tender age of 19, after a childhood spent in nearby Pennsylvania. The sketchbooks and journals recreate the naïveté and childlikeness of Haring at the time—qualities that, amazingly, he never lost. (The Keith Haring Foundation will post a page from these journals online each day so that you can journey along with Haring through all the simple wonders and the daily minutiae of his life as told in charming prose and more charming doodles.) Once settled in New York City, Haring found kindred spirits in the art world ranging from newcomers like himself (Scharf, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Basquiat’s then-girlfriend Madonna) to established stars such as Andy Warhol. To paraphrase Devo, these individuals asked Q: Are We Not Artists? A: We are [insert name here]! In the middle of this ad hoc family of artists, Haring emerged as its most fervent advocate—its loving, beloved heart.

Although the visual language remains the familiar “Haring”-speak, the media presented in this exhibition differs from the “usual” Haring fare. Of the 155 works on paper, many of them are either white chalk on black paper or black ink or graphite on white paper, making for a very black and white show that emphasizes the uniqueness of Haring’s draftsmanship—a simplicity that belied the humor and ideas behind the expressive characters. Looking at these illustrations as a group, I couldn’t help but think of Henri Matisse’s decorations for the Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence, for which the elderly Matisse designed simple but moving graphics for the interior that, when put beside Haring, could be taken for sacred graffiti. Haring’s subject matter, of course, is more profane than sacred, but “profane” in the sense of earthly in its explicit sexuality. The sexual Haring is not the Technicolor “Keith Haring for Kids” that reaches children of the next generation, but it is the Haring that can easily be forgotten in the sanitizing and ‘70s-izing of his achievement. In 2012 America, where contraception and gay marriage can still be up for debate, the sexual Keith Haring is as relevant today as when he was alive.

I found myself taken aback last week by a news story that more than twenty years had passed since Magic Johnson’s announcement in November 1991 that he was HIV positive. Seeing a beloved athlete announce that the still poorly understood disease of AIDS had entered his life remains one of the landmarks of that sad era. Today, Johnson is a TV basketball commentator and that announcement seems ancient history. Keith Haring died from complications from AIDS in 1990 at just 32 years of age. It may seem odd that such a short life could be dissected into tiny periods as Keith Haring: 1978–1982 does, but such dissection is necessary for us to see the total picture. Haring’s death remains another landmark of the AIDS era, but one that doesn’t shock as much today because Haring can seem so much a part of the distant past. By giving us the young(er) Haring, the pre-AIDS artist, we can see the life without the death that sealed, and in some ways sealed off, his legacy. Traces of Keith Haring live on (for good and/or ill) in the art of Banksy, Barry McGee, Shepard Fairey, and others and in the aesthetic DNA of modern fashion, product design, and even advertising. Keith Haring: 1978–1982 shows us how young Keith became the Keith we knew then and know today, but also how Haring took his childhood and translated the best parts of being a child—a sense of wonder, limitless imagination, and effortless acceptance of all—into his art.

[Image:Keith Haring (American, 1958–1990). Flyer for Des Refusés at Westbeth Painters Space, New York City, February 10, 1981 (detail). Acrylic and ink on paper. Collection Keith Haring Foundation. © Keith Haring Foundation.]

[Many thanks to the Brooklyn Museum for the image above and for other press materials related to the exhibition Keith Haring: 1978–1982, which runs through July 8, 2012.]