Can Today’s Paparazzi Ever Recover “La Dolce Vita”?

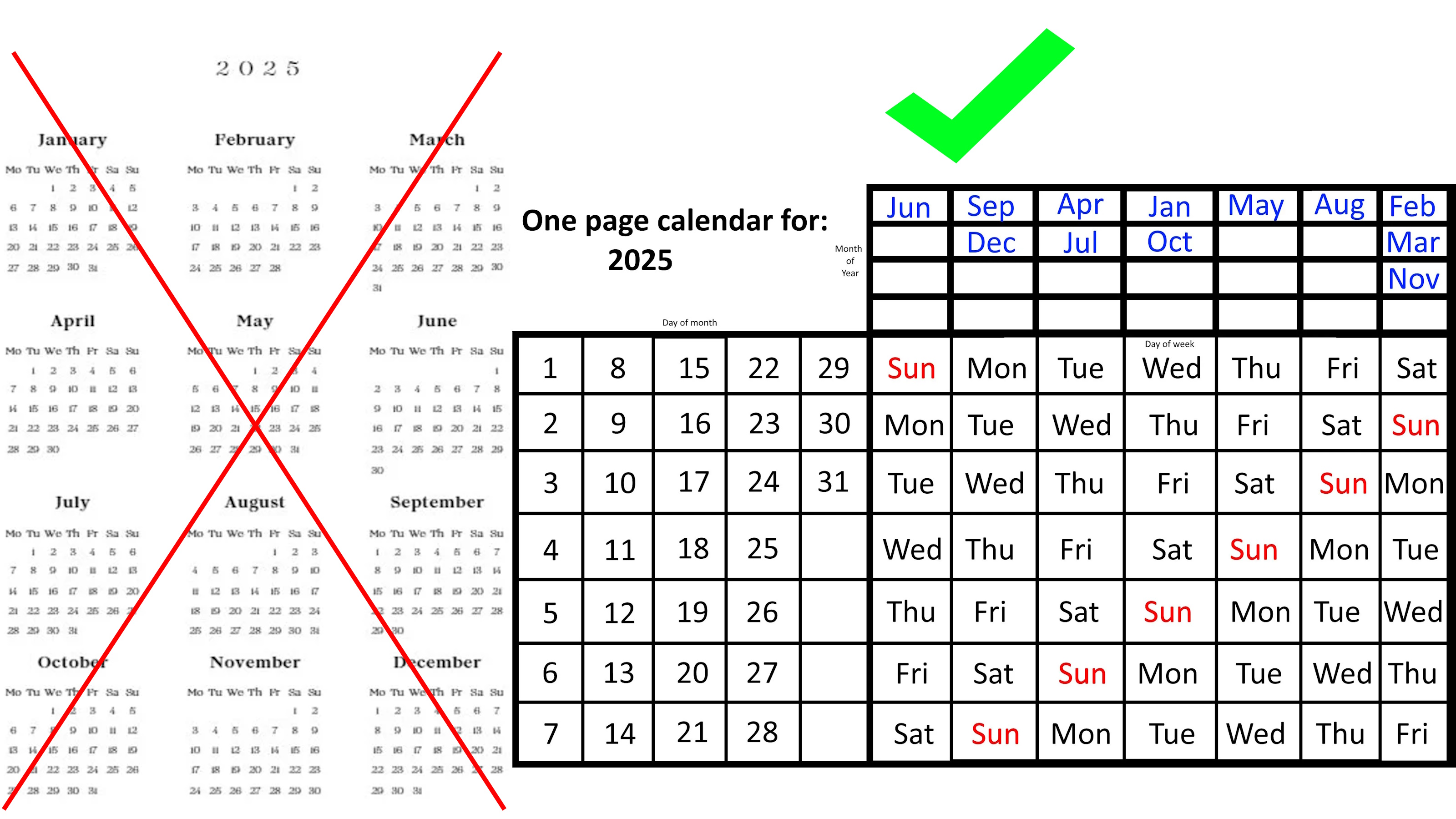

Why are today’s paparazzi so terrible? The combative relationship between photojournalists and their celebrity subjects seems to have become an all-out war as photographers look to capture content not already provided by the stars themselves via social media. That forbidden photographic fruit takes the form of either unguarded moments (the infamous “nip slips” and “upskirts”) or flagrant violations of privacy (helicopters over weddings, etc.), both of which lead to that quintessential paparazzi moment—the punch in the face. The Years of La Dolce Vita: The Birth of Celebrity Culture, which runs at the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art in London, UK, from April 30, 2014 through June 29, 2014, returns to the Italian roots of today’s paparazzi and raises the question of whether today’s photomedia can ever recover the grace and sweetness of those early days, the days of “La Dolce Vita.”

The name “paparazzi” actually comes from Federico Fellini’s 1960 film La Dolce Vita, in which Walter Santesso plays an annoying, celebrity-hounding photographer nicknamed “Paparazzo.” The Italian word suggests an annoying buzzing sound, like that of an insect you can’t shoo away. The paparazzi are the pluralized children of Santesso’s character, so right from the beginning they’ve been seen as a nuisance. Fellini’s film follows the misadventures of Marcello Mastroianni as Marcello Rubini, a gossip writer, as he pursues celebrities such as Anita Ekberg’s Sylvia. Fellini sets his story against the beautiful backdrop of Rome itself, with such memorable scenes as Sylvia’s impulsive dip into the iconic Trevi Fountain.

The Years of La Dolce Vita exhibition features the work of real-life paparazzo Marcello Geppetti (who, along with Rino Barillari and Felice Quinto, served as a model for the film character) and Arturo Zavattini, the cameraman on the film La Dolce Vita. While Zavattini provides behind-the-scenes glimpses of the filmmaking process, Geppetti captures the stars of the 1960s after hours taking in the Roman nightlife, especially along the Via Veneto, home of fashionable restaurants, bars, and nightclubs such as Caffe Strega, Rosati, and Club 84, where celebrities would come to party and the paparazzi would lie in wait for them.

In his catalogue essay “The Flow of Reality,” Massimiliano Di Liberto argues that “[t]he era of la dolce vita not only changed the image of Italy abroad, but was also a source of national pride and collective consciousness: through the world’s admiring eyes we rediscovered ourselves as attractive, with our history, our monuments, our culture, our capital city – so steeped in tradition and modernity at the same time.” Why was this rediscovery so important? “The whole of Europe was emerging from a devastating world war,” Di Liberto writes, “and hunger and poverty were common to all (can one draw parallels with the current economic crisis?).” After the almost total destruction of World War II, Italy and all of Europe had to rebuild not only physically, but also spiritually. The Italian film industry did what all filmmaking does best—it created a myth for people to believe in, specifically the myth of “La Dolce Vita,” the sweet life available to all who believe hard enough. The gossip industry and the paparazzi supplied the words and images to meet the growing demand for glamour and vitality that exuded from the celebrities and their films most powerfully in “the eternal city” of Rome.

Anyone who has spent any time in Italy knows that “doing as the Romans do” isn’t as easy as it sounds. Living “La Dolce Vita” takes practice, as Geppetti’s photos of Italian stars prove. Nobody looks good while eating, but somehow Marcello Mastroianni manages to in a bakery near Via Veneto in an August 1961 photo by Geppetti. When Geppetti photographs Pier Paolo Pasolini in his car in 1960, the acclaimed director looks in his rear view mirror, smiles, and waves stylishly to the fans and photographers behind him. Even while stuck in traffic, producer Carlo Ponti, actress Sophia Loren, and director Vittorio De Sica allseem to anticipate a night full of fun for Geppetti’s camera, with Loren’s huge eyes especially radiant. In 1967, Mastroianni smiles conspiratorially for Geppetti’s camera over the shoulder of a costumed dancer at the Teatro Sistina, as if to say with just his eyes, “Ain’t life sweet?”

For the most part, the American celebrities in Geppetti’s photographs just can’t pull off the same act. John Wayne standing on the edge of a fountain in Piazza Esedra in1965 in a light-colored suit and matching fedora looks painfully out of place, as if someone should find him a horse to ride off on. When James Stewart and his family cross the Via Veneto in1960, they seem huddled together against the foreignness. Even the usually unflappable Italian-American Frank Sinatralooks shocked by the cameras as he leaves the Teatro Quirino in a tuxedo in1962. A few Americans, however, manage to embrace the lifestyle. Jacqueline Kennedy in Ravello in 1962 with her daughter Caroline shows she’s not exclusively Franco-phile. (Elsewhere, just a year before his death in 1968, Robert Kennedy extends his arm to gently ward off Geppetti from his wife Ethel.) No American, however, matches the dynamic duo of blonde bombshell Jane Mansfield and her bodybuilder hubby Mike Hargitay before Geppetti’s lens. They play to the camera as Hargitay lifts a forkful of spaghetti to Mansfield’s glossy lips. Later, Hargitay lifts Mansfield into the back of a waiting car. With shoes already in hand and a glittery gown accentuating her cleavage, you could imagine the two of them racing off to the Trevi Fountain to recreate Ekberg’s iconic dip.

You can also argue that Elizabeth Taylor, the most famous star in the world at the time, embraced “La Dolce Vita” before Geppetti, but just with different husbands: with #4 Eddie Fisher as violinists serenade their car and with #5 (and #6) Richard Burtonkissing atop a yacht in Ischia. The shot of Burton and Taylor in 1962 recreated in real life the fictional passion of the film they were shooting at the time, Cleopatra, but caused a scandal as they were both awaiting divorces from their current spouses. That scandalous shot, so much more intrusive than Geppetti’s other images, feels like a transitional moment for the paparazzi and “La Dolce Vita.”

The one figure that seems the most conflicted in the exhibition of Geppetti’s photographs is one of the stars of Fellini’s film, the Swedish actress Anita Ekberg. In a 1962 photo, we see Ekberg sitting in the driver’s seat of her Mercedes. She meets Geppetti’s lens with a challenging stare as a cigarette smolders in her fingers at the end of her long arm dangling over the car door, as if she were tolerating the necessary evil of publicity only as long as her smoke lasted. Two years earlier, Ekberg did more than smolder, going so far as to approach paparazzi outside her home with a bow and arrow before resorting to pulling the hair of one photographer—all of which Geppetti captured on film. Franco Nero assault of Rino Barillari at the Trevi Fountain in 1965 may be the most reproduced image of celebrities gone wild on photographers, but Ekberg’s attack seems more unnerving because of the contrast between the actress’ composed on screen beauty and that ugly confrontation. It takes a lot to make someone pull a bow and arrow on you, so you can only imagine how far Ekberg was pushed.

If this paparazzi could get that ugly, how could anyone feel nostalgic about it? The answer lies in those moments and people in whom the photography of “La Dolce Vita” worked, and worked beautifully. Geppetti’s 1961 photograph of Brigitte Bardot in Spoleto (detail shown above) not only captures the starlet’s youthful appeal, but also simultaneously shows the frenzied press behind her. A similar shot from 1963 shows a smiling Bardot walking with a glass of wine in hand studiously oblivious to the wall of flashbulbs behind her. Even at the tail end of the “La Dolce Vita” period, in 1967, Bardot strides confidently and casually from the entrance of a restaurant into what must have been a gauntlet of cameras. Where Ekberg came unhinged, Bardot steeled herself together to play the game of celebrity and embody the dream that the viewing public wanted to believe in. Likewise, Arturo Zavattini’s on-set photographs of Federico Fellini making La Dolce Vita show an artist at work and at play. Intense behind the camera in one scene, Fellini’s equally relaxed lifting actress Nico Otzak’s blonde locks as she rests her head on assistant cameraman Ennio Guarnieri’s leg. The world Zavattini presents might be as ephemeral as the almost magical puff of smoke from Mastroianni’s cigarette in one photograph,but it’s the same game of smoke and mirrors that celebrities have always played and the public’s always heartily played along with.

Can the paparazzi ever play the game by the rules of “La Dolce Vita” again? “It is clear that we live in a new era of devastating visual pollution from every point of view,” Di Liberto laments in his essay. “Our society is steeped in it, and its resulting representation constitutes a methodical reflection of transience, of impermanence. This rapid fading of news, of facts and of images produces a disturbing feeling of vertigo. It is not images that we lack, it is the ability to select them.” For Di Liberto, that lack of permanence leads to a lack of identity. The Italian people and post-war world internationally bought into “La Dolce Vita” and the imagery of that myth because they wanted to forget the bitterness of the war as they built a new future. The Years of La Dolce Vita: The Birth of Celebrity Culture looks back at the birth of celebrity culture in all its strengths and weaknesses. As Roberta Cremoncini, the Director of the Estorick Collection, recounts in her catalogue introduction, Mastroianni, the star of La Dolce Vita, saw the film as “a joyously apocalyptic sketch of contemporary society,” “an exploration of the problems of our time in a luxurious, baroque frame,” and “a warning with regard to the precipitous course along which we are heading towards an inglorious end.” So, even the makers of the myth of “La Dolce Vita” knew its false promises as well as its mythic value. Have we reached the “inglorious end” Mastroianni warned of more than half a century ago? Or can we regain a sense of “La Dolce Vita” to combat the bitterness of recent global economic strife? If we’re ever to regain a sense of grace—the sweet life—we may need to follow the stars and the possibility of living extraordinarily, perhaps as captured by the paparazzi for public consumption. If not, the future might turn out to be one long Lindsay Lohan upskirt to annihiliation.

[Image:Marcello Geppetti (1933-1998). Brigitte Bardot in Spoleto, June 1961. MGMC & Solares Fondazione delle Arti.]

[Many thanks to the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art in London, UK, for the image above from, press materials related to, and a review copy of the catalogue to the exhibition The Years of La Dolce Vita: The Birth of Celebrity Culture, which runs from April 30, 2014 through June 29, 2014.]