Are Seekers of Politically Autonomous Art Barking up the Wrong Tree?

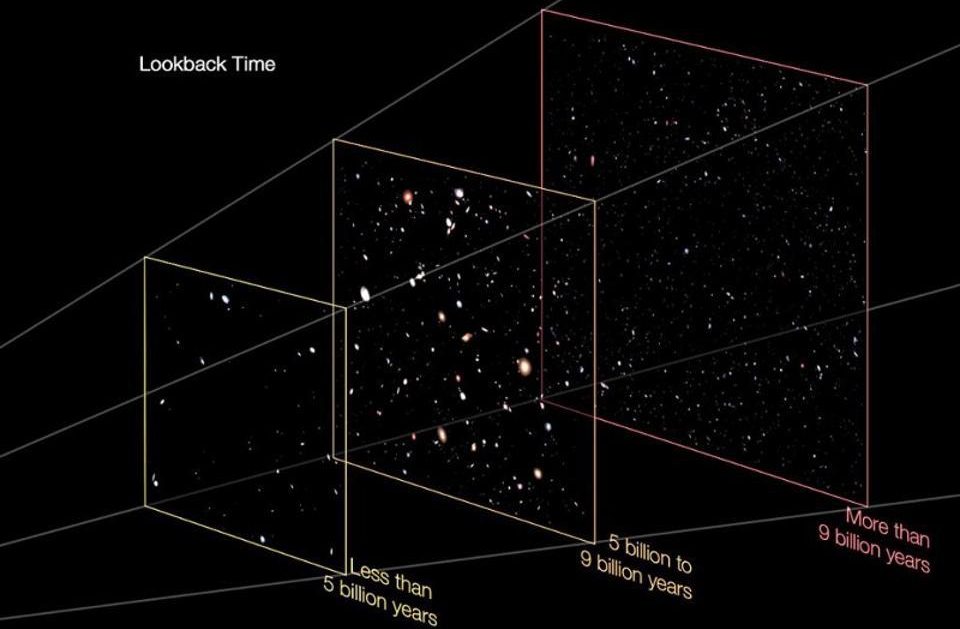

With the presidential election less than a month away, it’s hard to go to a museum or gallery in the United States right now and not see art that either directly or indirectly references the election. In his essay, “Autonomy in Conservative Times,” Bret Schneider describes how the idea of autonomy has “crept into the lexicon of contemporary art,” despite the fact that the debate itself over autonomy in art is “passé.” Schneider sees the whole revisiting of political autonomy as a huge misinterpretation, but a misinterpretation that holds important implications for society today. Are people pursuing political autonomy in art, like the title pooch in Joan Miró’s Dog Barking at the Moon(from 1926, shown above), barking up the wrong tree for a reason?

Schneider splits the debate into two camps: the “pure art” people versus the “political art” people. The “pure art” people cling to the antiquated “art for art’s sake” philosophy of the 19th century. The “political art” people cling to the Marxist-based critique that all art in some way engages the political. Where the “pure art” people want to put the artist and the art in a protective, politically resistant bubble, the “political art” people burst that bubble as an impossibility. Schneider sees the significance of this renewed battle in our cultural grasp of reality. “The separation of art-for-arts sake and political art is a vulgar one,” he writes, “and harbors vulgar ideas of society that are not limited to artistic discourse: that there is a ‘concrete’ ‘lived world’, and a fantasy land of art that does not exist in the world.” If art’s just a fantasy, then why pay attention? I’m oversimplifying much of what Schneider says so much more eloquently (so read the whole thing), but, for me, the main point is the American conservative goal of divorcing politics from art, whether that art’s Robert Mapplethorpe or Big Bird.

Schneider’s analysis of political autonomy reminded me of the Joan Miró: The Ladder of Escape exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, this past summer. Miró somehow managed to create an art that was politically engaged without descending into partisan propaganda in the worst sense of the word. “Miró was vocal about his contempt for the political cooption of art and artists,” Robert S. Lubar writes in the catalog to the exhibition. “He was committed to the idea of revolutionary struggle and social emancipation, but spoke out against what he called ‘social painting’ (i.e., Social Realism) as little more than political propaganda.”

Miró’s use of ladder imagery, such as the ladder to the moon in Dog Barking at the Moon, becomes a “ladder of escape,” according to Marko Daniel and Matthew Gale, that “signals his desire for withdrawal to his own artistic world.” Despite this desire, Miró couldn’t resist the real world pressures of the Spanish Revolution and World War II, so “the ‘ladder’ of his imagery is unavoidably grounded in reality, and escape is born of awareness.” Miró walks a fine line in creating abstract, Surreal imagery that still addresses, however obliquely, political realities. The dog barks at the moon—an unobtainable ideal—but the ladder hints that there may be some way to reach the lunar surface from a grounded foundation in reality. It’s not lunacy, or partisan mania, but rather a hopeful faith in humanity in the face of the rampant inhumanity Miró witnessed firsthand in his country.

Schneider refers to today’s “conservative times” as perhaps the origin of this renewed interest in autonomous, apolitical art. So much political art targets conservatism from a far left position that it’s understandable that conservatives would call for a cease fire. In the example of Joan Miró, however, we might see a better alternative to a cease fire—a sane approach to being political without being blindly partisan. Miró only wanted what was best for his Spanish homeland, regardless of who held the reins of power. We should all want the same thing when this election is over.

[Image:Joan Miró. Dog Barking at the Moon, 1926. Oil on canvas. Unframed: 73.03 x 92.08 cm (28 3/4 x 36 1/4 in.). Framed: 87.6 x 107 x 7 cm (34 1/2 x 42 1/8 x 2 3/4 in.). Philadelphia Museum of Art, A.E. Gallatin Collection, 1952. © 2012 Successió Miró/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.]

[Many thanks to the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC, for providing me with the image above and a review copy of the catalog to the exhibition Joan Miró: The Ladder of Escape.]