Andy Warhol, Digital Art Pioneer?

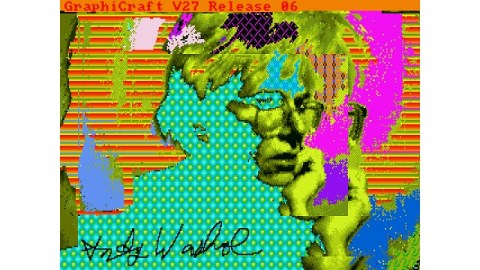

It all started with a video on YouTube. Sometime in 2011, artist Cory Arcangel watched a video of Andy Warhol painting a digital portrait of singer Debbie Harry in 1985 on a Commodore Amiga 1000 as part of a promotional event for the computer’s release. What happened to that image and the others Warhol made on that computer nearly 30 years ago?, Arcangel wondered. When Arcangel traveled to Pittsburgh later that year for his upcoming exhibition at the Carnegie Museum of Art, he stopped off at the nearby Andy Warhol Museum and asked that very question of the curators. That YouTube video and Arcangel’s curiosity set off a chain of events that led to the recovery of those long-forgotten images from the depths of the digital archives and the tomb of obsolete technology. Compared to what artists such as Arcangel and others can do with modern computer technology today, Warhol’s images (such as his self-portrait, shown above) seem like quaint cave drawings. But there’s still something to be learned from looking at the first foray into a new medium for an already established artist such as Andy Warhol, who may now be seen perhaps as a digital art pioneer.

The video begins with Warhol and Harry descending a staircase onto a stage upon which the Amiga 1000 has been set up. Warhol and a tuxedoed Commodore representative sit at the computer while Harry poses at a distance. The computer expert guides Warhol through the steps of taking a “digital picture” of Harry and then using the graphic interface to manipulate the image with fills and other effects. As Warhol plays around with the computer, the expert tries to interview him, only to get the typical affectless Andy responses of “Uh, yes” or “Uh, no.” Asked how often he’s worked on a computer, Warhol answers that this is his first time, which is not surprising given Warhol’s age at the time (56; he would die just 2 years later) and the fact that personal computing was still in its infancy in 1985. Looking at Warhol’s awkwardness with the mouse and the now-painfully processing speed of the computer’s graphics will amuse the younger set, but watching Warhol come to grips with this new technology for the first time is an invaluable document comparable to being there in the fields with the Impressionists using the newfangled technology of the paint tube that freed them from the confines of the studio to go out in nature with a new degree of freedom that revolutionized painting itself.

Alas, Andy lived only another 2 years to enjoy this new medium. The Amiga 1000 might look like a dinosaur by today’s standards, but some consider it the first multimedia computer, far ahead of its time even though Commodore itself as a company couldn’t stay far ahead of its competition, lasting just a decade after introducing the Amiga 1000. The images Andy made that day might have disappeared, too, except for the efforts of the Carnegie Mellon University Computer Club and the Frank-Ratchye STUDIO for Creative Inquiry. The student-run Computer Club used their extensive collection of obsolete computer hardware and their prize-winning retro-computing software to recover Warhol’s Amiga 1000 images from the disc languishing in the Warhol Museum’s archives. In addition to the Harry portrait, which had never been lost, the images Warhol created for the commission by Commodore range from simple doodles to riffs on some of his favorite subjects—Marilyn Monroe, Campbell’s Soup, self-portraits, snippets from art history such as Botticelli’s Venus, and the banana he used for the Velvet Underground & Nico’s iconic album cover.

What would Warhol have done with today’s advanced computers? Synonymous with Pop Art in his own day, Warhol today would bask in the way computers permeate our popular culture today and create art that reflected that reality—an iPad triptych, perhaps, to update his Marilyn Triptych the same way that the Marilyn Triptych updated the religious triptychs of centuries before. Warhol would probably see the computer as today’s (false?) idol worshipped above all others, thus continuing the line of social commentary that his earlier work began. It’s the same old story, just with different characters and gods. (If Henry Adams were alive today to write his Education of, he’d be musing not over the Virgin and the Dynamo but the Virgin and the iPhone.) I doubt Warhol would use computers solely for their potential as a medium the way that another canonical artist, David Hockney, does with his iPhone and iPad drawings. For Warhol, the medium was always the better part of the message, with the concept of craft taking a back seat. When Warhol watches the fill effect slowly turn Blondie’s portrait canary yellow in the video, the cool factor clearly outweighs aesthetic considerations.

Digital art today has grown exponentially in its potential along with the potential of computing itself. But if Moore’s Law holds true and computing power doubles approximately every two years, can human creativity itself keep up that pace? Warhol’s not a “pioneer” of digital art in the sense that he created great works of digital art. However, Warhol is a pioneer in the sense that his approach to popular culture and the media it uses to communicate provides a template for us to perhaps keep pace with the computing world that threatens to, as Neil Postman warned back in 1985, the year Warhol doodled on that Amiga 1000, amuse us to death.

[Image:Andy Warhol. Andy2, 1985. ©The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visuals Arts, Inc., courtesy of The Andy Warhol Museum.]

[Many thanks to The Andy Warhol Museum for providing me with the image above and other press materials.]