Why the simulation hypothesis is pseudoscience

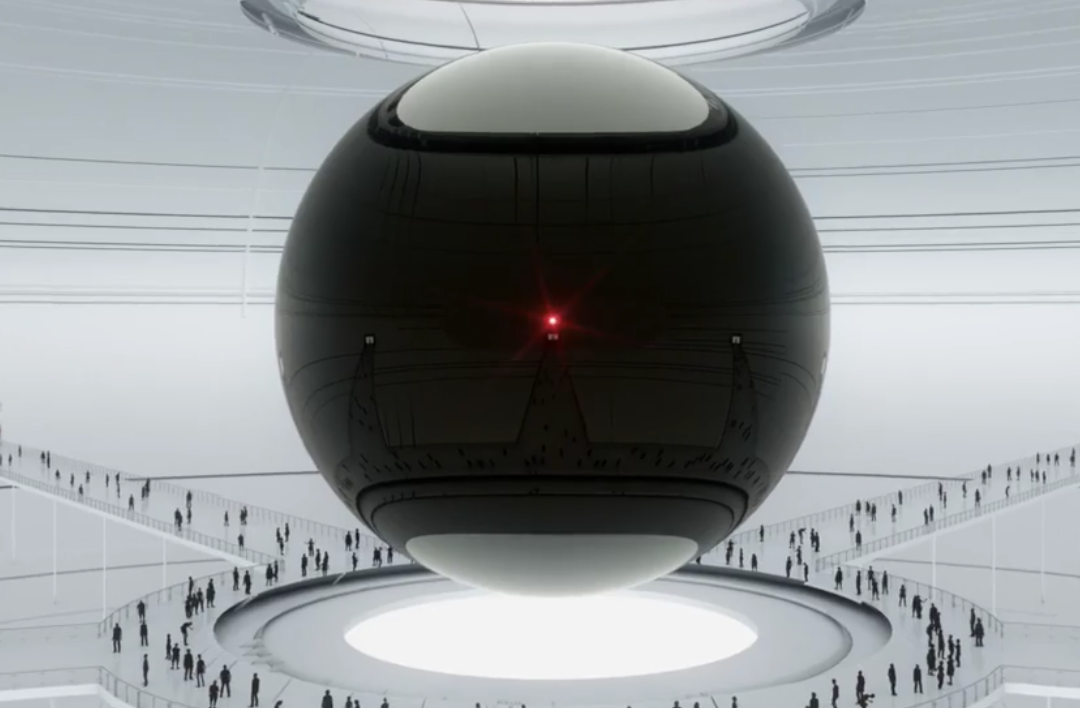

- The simulation hypothesis posits that everything we experience was coded by an intelligent being, and we are part of that computer code.

- But we cannot accurately reproduce natural laws with computer simulations.

- Faith is fine, but science requires evidence and logic.

The following is a transcript of the video embedded at the bottom of this article, which was republished with the permission of Dr. Sabine Hossenfelder. The original article is here.

I quite like the idea that we live in a computer simulation. It gives me hope that things will be better on the next level. Unfortunately, the idea is unscientific. But why do some people believe in the simulation hypothesis? And just exactly what’s the problem with it? That’s what we’ll talk about today.

According to the simulation hypothesis, everything we experience was coded by an intelligent being, and we are part of that computer code. That we live in some kind of computation in and by itself is not unscientific. For all we currently know, the laws of nature are mathematical, so you could say the universe is really just computing those laws. You may find this terminology a little weird, and I would agree, but it’s not controversial. The controversial bit about the simulation hypothesis is that it assumes there is another level of reality where someone or something controls what we believe are the laws of nature, or even interferes with those laws.

The belief in an omniscient being that can interfere with the laws of nature, but for some reason remains hidden from us, is a common element of monotheistic religions. But those who believe in the simulation hypothesis argue they arrived at their belief by reason. The philosopher Nick Boström, for example, claims it’s likely that we live in a computer simulation based on an argument that, in a nutshell, goes like this. If there are a) many civilizations, and these civilizations b) build computers that run simulations of conscious beings, then c) there are many more simulated conscious beings than real ones, so you are likely to live in a simulation.

Elon Musk is among those who have bought into it. He too has said, “It’s most likely we’re in a simulation.” And even Neil DeGrasse Tyson gave the simulation hypothesis “better than 50-50 odds” of being correct.

Maybe you’re now rolling your eyes because, come on, let the nerds have some fun, right? And, sure, some part of this conversation is just intellectual entertainment. But I don’t think popularizing the simulation hypothesis is entirely innocent fun. It’s mixing science with religion, which is generally a bad idea, and, really, I think we have better things to worry about than that someone might pull the plug on us. I dare you!

But before I explain why the simulation hypothesis is not a scientific argument, I have a general comment about the difference between religion and science. Take an example from Christian faith, like Jesus healing the blind and lame. It’s a religious story, but not because it’s impossible to heal blind and lame people. One day we might well be able to do that. It’s a religious story because it doesn’t explain how the healing supposedly happens. The whole point is that the believers take it on faith. In science, in contrast, we require explanations for how something works.

Let us then have a look at Boström’s argument. Here it is again. If there are many civilizations that run many simulations of conscious beings, then you are likely to be simulated.

First of all, it could be that one or both of the premises is wrong. Maybe there aren’t any other civilizations, or they aren’t interested in simulations. That wouldn’t make the argument wrong of course; it would just mean that the conclusion can’t be drawn. But I will leave aside the possibility that one of the premises is wrong because really I don’t think we have good evidence for one side or the other.

The point I have seen people criticize most frequently about Boström’s argument is that he just assumes it is possible to simulate human-like consciousness. We don’t actually know that this is possible. However, in this case, it would require an explanation to assume that it is not possible. That’s because, for all we currently know, consciousness is simply a property of certain systems that process large amounts of information. It doesn’t really matter exactly what physical basis this information processing is based on. Could be neurons or could be transistors, or it could be transistors believing they are neurons. So, I don’t think simulating consciousness is the problematic part.

The problematic part of Boström’s argument is that he assumes it is possible to reproduce all our observations using not the natural laws that physicists have confirmed to extremely high precision, but using a different, underlying algorithm, which the programmer is running. I don’t think that’s what Boström meant to do, but it’s what he did. He implicitly claimed that it’s easy to reproduce the foundations of physics with something else.

But nobody presently knows how to reproduce General Relativity and the Standard Model of particle physics from a computer algorithm running on some sort of machine. You can approximate the laws that we know with a computer simulation – we do this all the time – but if that was how nature actually worked, we could see the difference. Indeed, physicists have looked for signs that natural laws really proceed step by step, like in a computer code, but their search has come up empty-handed. It’s possible to tell the difference because attempts to algorithmically reproduce natural laws are usually incompatible with the symmetries of Einstein’s theories of Special and General Relativity. I’ll leave you a reference in the info below the video. The bottom line is it’s not easy to outdo Einstein.

It also doesn’t help, by the way, if you assume that the simulation would run on a quantum computer. Quantum computers, as I have explained earlier, are special-purpose machines. Nobody currently knows how to put General Relativity on a quantum computer.

A second issue with Boström’s argument is that, for it to work, a civilization needs to be able to simulate a lot of conscious beings, and these conscious beings will themselves try to simulate conscious beings, and so on. This means you have to compress the information that we think the universe contains. Boström therefore has to assume that it’s somehow possible to not care much about the details in some parts of the world where no one is currently looking, and just fill them in case someone looks.

Again though, he doesn’t explain how this is supposed to work. What kind of computer code can actually do that? What algorithm can identify conscious subsystems and their intention and then quickly fill in the required information without ever producing an observable inconsistency? That’s a much more difficult issue than Boström seems to appreciate. You cannot in general just throw away physical processes on short distances and still get the long distances right.

Climate models are an excellent example. We don’t currently have the computational capacity to resolve distances below something like 10 kilometers or so. But you can’t just throw away all the physics below this scale. This is a non-linear system, so the information from the short scales propagates up into large scales. If you can’t compute the short-distance physics, you have to suitably replace it with something. Getting this right even approximately is a big headache. And the only reason climate scientists do get it approximately right is that they have observations which they can use to check whether their approximations work. If you only have a simulation, like the programmer in the simulation hypothesis, you can’t do that.

And that’s my issue with the simulation hypothesis. Those who believe it make, maybe unknowingly, really big assumptions about what natural laws can be reproduced with computer simulations, and they don’t explain how this is supposed to work. But finding alternative explanations that match all our observations to high precision is really difficult. The simulation hypothesis, therefore, just isn’t a serious scientific argument. This doesn’t mean it’s wrong, but it means you’d have to believe it because you have faith, not because you have logic on your side.