MICHELLE THALLER: One of my absolute favorite things about being an astronomer is we are actually time travelers-- real time travelers. We work all the time with looking back into the history of the universe. And there's a wonderfully simple reason why. And that's that light only has a finite speed. As fast as light speed is-- light goes at 186,000 miles per second. That's incredible. But as fast as that speed is, when you think about how large the universe is, light takes time, a lot of time, to actually get to us from distant objects. So let's start off with the nearest star. It's kind of the simple way to begin.

So the sun is about 93 million miles away. And at 186,000 miles per second, it takes about eight minutes for light to actually get to us from the sun. So when you stand on the surface of the Earth today and look up at the sun-- with eye protection-- you're actually seeing the sun as it was eight minutes ago. There's no way you can see the sun as it is right now, because the light has to take time to travel that 93 million miles to us. So even in our own solar system, you actually look back into the past. Depending on where the planets are-- planets like Mars, maybe you're looking at something on the order of 15 minutes away, by the time you get to the outer planets, you're looking at things that are many hours away.

So even our own solar system is looking back into the past as you look farther out into space. But then things start to get much more dramatic as you look farther and farther away. And in fact, the nearest star to us in the sky, Alpha Centauri, is four light years away. That's the time it takes light to travel in one year. One light year is about 6 trillion miles. There's no way you can see Alpha Centauri the way it is now. You're seeing it as it was four years ago. You go farther out, and soon this becomes very dramatic. The nearest galaxy to us, Andromeda, is 2 million light years away. So when you look up at Andromeda, you're looking at light that came to the earth at the very, very dawn of the human species.

Two million years ago, we were fairly different than we are now. The farthest we can see, you're actually looking back billions of years-- you're actually looking back at light that's coming to you today, the light is actually arriving at your eyeballs today-- before the earth even formed. And the farthest away we can see is actually quite breathtaking. We can see a distance that corresponds to a time about 400,000 years after the Big Bang. That's something like 13 billion years ago. The light actually took 13 billion years to get to us. And the thing that's so powerful about that as a scientist is, over that much time, things start to look very different. Even in the course of a few million light years away, galaxies look pretty much the same way they do now. The stars look very much the same, the galaxies look a lot like the Milky Way.

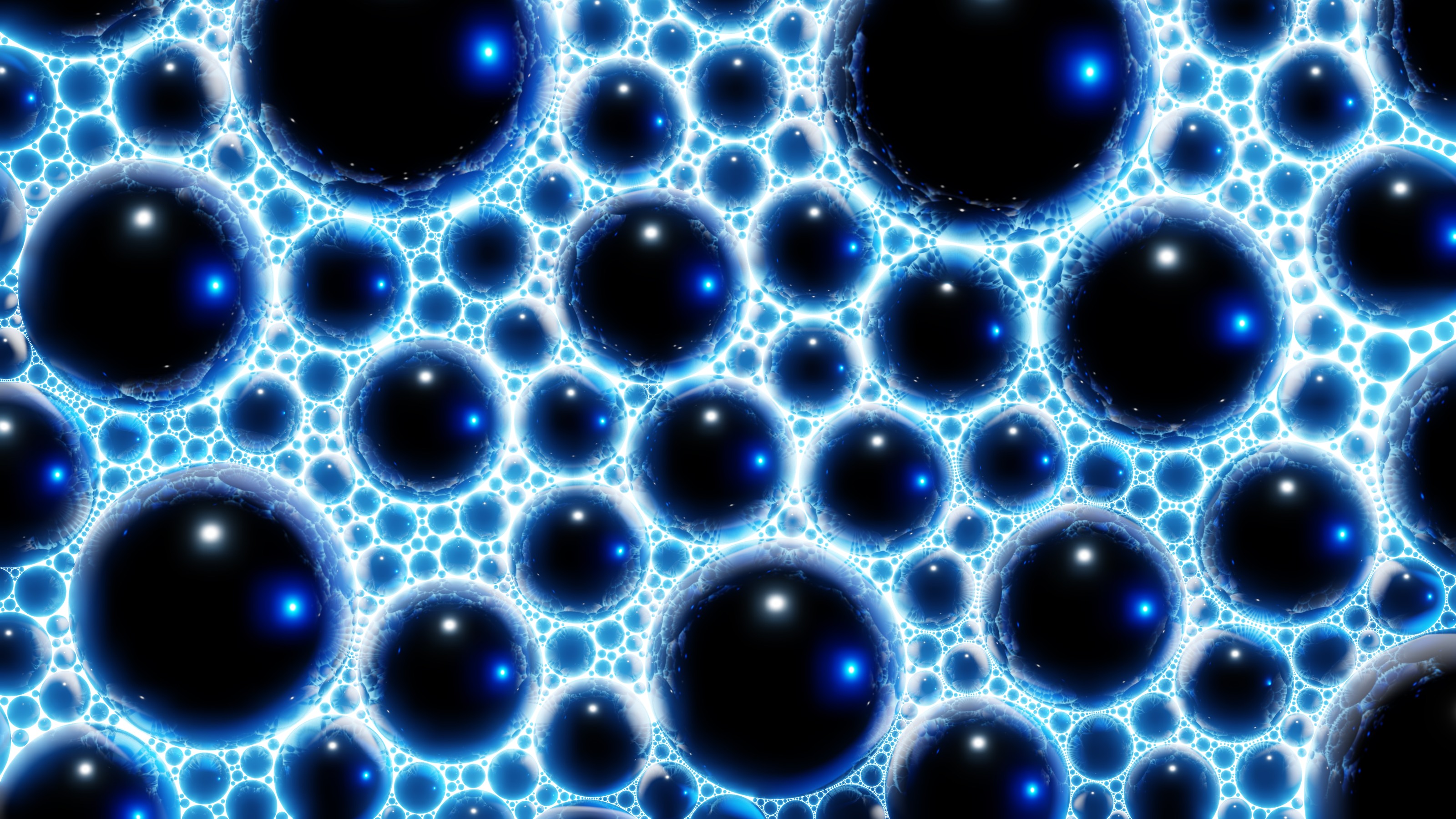

But as you go farther and farther out into space and the light has taken longer to reach you, things begin to change very dramatically. Galaxies don't look the same. They tend to be smaller, they tend to be more active, they have very active black holes at their centers that we don't see around the nearby galaxies today. So the conditions must have been different billions of years ago for these giant black holes to have all this stuff falling into them. We even see, as you look very far out, the chemistry of the universe begins to change. Because, amazingly, every element besides hydrogen and a little bit of helium was formed by dying stars so when you look back billions of years, there have been fewer stars that formed elements like oxygen, and carbon, and iron, and everything else that makes up me, besides hydrogen.

The farthest out we can see, 400,000 years after the Big Bang, we actually see in microwave observations. And these are actually very large observations on the sky. We don't see a lot of detail. The pixels are very big. We can't really see individual things out there. But we see that the entire universe, 400,000 years after the Big Bang, was all very hot hydrogen gas, and that's it. And that's real. That's not a theory. That's not something that we actually are using mathematics to try to describe. That's a picture if you look out into space in any direction in the sky-- we've actually done the entire sky, all around us. If you look out to that distance, all you see is very hot hydrogen gas at very nearly the same temperature.

The variations are much, much less than a single degree across the entire sky. Every way you look, in every direction away from you, you look back in time, until finally you get to the when the universe was nothing but hot hydrogen. And that's actually as far as we can see. And the reason is, any farther out, you're looking back to a time when the universe was so hot and so dense it was actually opaque to light. It's like looking at the surface of the sun. So pick any direction on the sky, look out to a time 13 billion years ago, and what you see is something very much like the surface of the sun, very hot hydrogen gas, all around us. This is one of the most amazing observations ever made. We actually have a real time machine that allows us to look back and see how the entire universe formed up to that point. And then we can't see anymore because it was so hot. We definitely need more detailed observations.

And the next generation of space telescopes is going to go after the details-- how did the very first stars form? Because that light is still reaching us tonight. I mean, tonight, up in the sky, it's too faint for your eyes to detect, but with a giant telescope, there's light arriving today from 12 billion years ago, the first generation of stars, and our new instruments are going to be able to catch that. So as we look out into the universe, it's all right there. We have a ringside seat to see how everything formed and everything changed, ever since the Big Bang.