When the world has gone corrupt, who can you trust? Blockchain is stepping up. The word might ring a bell for its connection with Bitcoin, but internet pioneer Brian Behlendorf is looking at this technology beyond its use in cryptocurrency. Blockchain is an open ledger system where transactions are irreversibly recorded and immediately shared to a distributed network of witnesses (companies, agencies, individuals). The beauty of this idea is in its decentralization—if no one person or institution holds power, then that power cannot be abused. The potential for this technology is enormous: it could significantly lower corruption and eliminate fraud in many industries like banking, freight, construction, and even trace the provenance of goods like diamonds. “Blockchain technology allows us to build these same kind of systems but in a world where we don’t want to or we can’t trust central actors,” says Behlendorf. Here he describes how a blockchain system is being used to protect civilian land titles in developing nations, and demonstrates how blockchain could have prevented or severely lessened the impact of the 2008 financial crisis. Brian Behlendorf is the executive director of Hyperledger; for more info, visit hyperledger.org.

Brian Behlendorf: What are the strengths of the blockchain technology? The strengths are that we can take many business processes today—and by business processes you might even include land titles and buying and selling a home, you might include provenance tracking of products like diamonds and food supply, that sort of thing. One of the real strengths is being able to take these systems that today depend very much on bureaucracy and paperwork—very human processes for sure, but processes that get bogged down—and actually automate them and cut the cost of a lot of this, but also, by automating them, improve the auditability of them.

People pay a lot of money to have third-party auditors come in and make sure that the claims that are in their books are actually real. It’s a tremendous burden and it’s why bureaucracy often requires three signatures to do anything interesting. To send a shipping container, for example, from Asia to the United States, about half the cost of that is in the paperwork involved in coordinating between 20 to 30 different organizations for sign off, from the biller materials all the way to the person it’s delivered to.

If blockchain technology can help us automate these systems, make them more efficient, it may also ensure that we keep the opportunities for fraud and the opportunities for corruption to a minimum. If we make it hard to steal people’s land, or to ship illicit product in shipping containers—or simply in approving a permit for construction on your home, holding that up for days or months until you pay me an expediter fee—which all too often happens in home remodeling—if we can make these processes a bit more automated, more transparent, then I think we can do a lot to improve society in these ways.

And that kind of wraps together two or three different advantages of this. The other advantage is: it’s a fun space to be in. There’s a lot of dynamic thinking going on, a lot of new companies, a lot of technologists talking about very far-off concepts, and it’s finally a place to get people excited about technology, especially as it is so much about decentralization.

What are the challenges? One of the challenges right now for sure is that it’s early days with the technology. There are a couple of places where there’s clearly a lot of value being created, there’s clearly a lot of activity, say, in the cryptocurrency space, but in many ways, again, like the early days of the web we don’t yet know what the big winners will be from the technology, but we know that this is something everybody will need in one way or another.

So the challenge right now is that there are a lot of options, and many of them are fairly immature when it comes to actually building and running them for big systems. That’s one reason we’ve chosen, at Hyperledger, to focus on: what are the simplest things we can do now and ship out as product that people can use that they can actually run?

And the second thing is really understanding that—and this is really hard for many industries and many actors in industries—every use case I could give you around where blockchain technology is applicable, you could always come back to me as a technologist and say, “Wouldn’t this be more efficient, faster, cheaper to do as a central database? Isn’t somebody just going to pull a Google or pull an Amazon and build a central database to track all the fish supply catches and shipping this or that?”

And the answer is always yes, that it is more efficient and cheaper, but it’s also expensive when you think about the cost of having, politically and from a business perspective, having a central actor in a marketplace. Many marketplaces simply don’t want that.

The banks of the world don’t want one big bank at the center. People who care about their land title worry about the corruptibility of the land title office. In certain countries that’s a big issue.

Blockchain technology allows us to build these same kind of systems but in a world where we don’t want to or we can’t trust central actors. And that’s hard to wrap your head around, especially because everyone believes they can be trusted. “Hey, if I’m the center of a market you can trust me! What do you mean you can’t trust me?” It feels like a very personal affront, perhaps, even to say that. But it’s essential, I think, to realize you can’t really grow your market beyond those who can really trust you if that’s your business model.

So that’s, I think, hard for some people to get the conceptual model around, just like it might’ve been hard in 1993 to understand what it means to send an email to someone on the other side of the planet or to buy a television or buy a car through a website. You would’ve been told you were crazy to think that people would be doing that in 1993, now we take it almost for granted. So these are the challenges, but I see many people addressing these challenges.

But most recently I was a venture capitalist. And so I looked at a lot of different companies, including companies in the Bitcoin space, and increasingly the blockchain space, and I was kind of bored by all the examples I was given until I saw one company approach us and talk about land titles and emerging markets. Land titles—why would that be interesting?

Well, there’s an economist named Hernando de Soto who wrote a book 'The Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid', who talked about how in many countries citizens don’t have title to the land that they might have been living on for generations.

Where a title is something we understand as a set of documents recorded by a county registrar or in a government office that allows us to prove not only to someone we’re hoping to sell some property to that we actually own it, but also prove to a mortgage lender that we have this property, and we’d like a loan and if we fail to pay the loan then they get the property. That’s something that many people in the emerging markets do not have access to or historically have not.

So many countries started to digitize and introduce land titling systems and realized they had a problem where if that was digital it was also very easy for somebody to corrupt.

It’s easy for a government bureaucrat who desired a piece of property, perhaps for their son to have some beachfront property north of the capital or because an oil company wanted to come in and drill, it was pretty easy for them to step in and erase all history of somebody’s ownership of property in a way that—because it’s digital—disappears forever. When something is paper, yes, you can set fire to a paper record, but it’s actually really hard to completely eliminate a rich paper trail in something like land title.

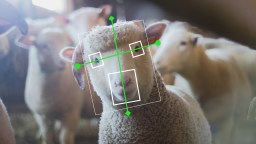

So this is a problem and the solution to that problem that this company had come up with was to implement a land title system as a distributed ledger, as a database—but one that is shared immediately, every time something is recorded into this database it's shared with a large circle of other companies and agencies and NGOs that act as witnesses for that transaction.

And if somebody’s land was taken away from them, A, it would be noticed very quickly; that person would have a history of what happened on that property and they would be able to see that immediately, but B, if their signature wasn’t on the right document, it wouldn’t even be accepted as a transaction on that network.

So land titling, and the reason I bring it up here is this is interesting when you’re talking about a country like Honduras or the Republic of Georgia or Estonia like other countries that have started to adopt this for economic development reasons, but think about the mortgage crisis in 2008.

For any of you who have seen the movie 'The Big Short', you remember these scenes of panic selling of these instruments which were tranches of risk in the mortgage industry where nobody really had a clear understanding of what the underlying assets were, the houses and the mortgages that pointed to those houses; who owned the paperwork for those mortgages? Who owned the title on those homes? This was data that was lost inside of these bureaucracies that didn’t have the manpower to respond to the queries, and in many cases you ended up with people selling assets for pennies on the dollar and for people with homes with 95 percent paid-off mortgages getting eviction notices from somebody who owned less than a percent of the interest in that mortgage.

All of this to say there are many people who believe that if blockchain technology had been implemented at the beginning of the 2000s for the land title and mortgage industry, not only would you have had the data there to understand who owned these assets, but those mortgages, if they had been built as smart contract systems and those tranches of risk as smart contract systems, that unwinding process where everybody felt like they needed to move out of that asset might have been a more orderly, programmatic, 'Here’s all the data, here’s how it plays out; now we don’t have to sell it for pennies on the dollar, we can sell it for ten percent off of the price that we thought it was actually worth.'

And that might have saved a lot of peoples' homes, avoided a lot of real friction in the market but also a lot of the volatility that we saw. And so the opportunity for distributed ledgers to both give us new capabilities but also help us with auditing, help us with the stability of markets, even in scenarios where trust is really at a premium—that’s the real potential here. And this might sound like back-office or science fiction kind of scenarios, but that’s what’s driving a tremendous amount of interest in the industry today.