A conversation with the Nancy R. McPherson Professor of Business at the Harvard Business School.

Regina Herzlinger: I’m Regina Herzlinger. I’m the Nancy R. McPherson Professor of Business at the Harvard Business School.

Question: How can we reduce health care costs?

Regina Herzlinger: Health care is a hugely inefficient industry.

McKinsey analyzed the American health care system versus health care systems in other countries, and it came up with the figure that there is about half trillion dollars of, I would put it, waste, in the US health care system.

The biggest source of waste is the way we treat people with chronic diseases like diabetes, aids, heart disease, cancer, people who have chronic disabilities like bad backs. We treat them in a very fragmented way.

We have no one organization that is responsible for everything that the person with diabetes has, everything that the person with AIDS needs.

These people have tremendously complicated needs. Their diseases are multifactorial and they manifest themselves in many different ways.

What we need is a health care system that’s organized around the needs of the patient for total care for their diseases, total care for their disabilities. What we have is a health care system that’s organized by inputs, doctors, hospitals, nursing homes.

Each one of these inputs, each one of these providers what did they want? Well, they’re human. What they want is they want to make sure that they maximize their share of their pie. Maximizing their share of the pie is not the same as doing what’s best for that patient.

Question: In what way should health care be focused on outcomes?

Regina Herzlinger: What do we know about outcomes in health care? Well let’s say you needed a mastectomy. How much would you know about the surgeon who’s going to perform that mastectomy on you? About her mortality rates, how many people like you died when they got this surgery? About her morbidity rates? How many people became infirm? How many people got a deadly clot? How many people had a sponge left inside their body? How many people got an infection that they absolutely could not check? How many people were readmitted 30 days, 60 days, 90 days to keep #### preparing what’s going wrong with that surgery? Do you know where you could find that information? I don’t either.

Clearly what we need is much more transparency in health care.

I have long proposed the health care equivalent of the SEC [Securities Exchange Commission]. SEC has been a miserable failure in its regulatory functions, but transparency--it’s incredible. Countries all over the world emulate the transparency functions of the SEC. I can go to the SEC’s website and within three seconds I can find most of what I would want to know about any publicly traded corporation.

What can I know about my doctor, my hospital, my insurer, my dialysis center? Zero.

We need a federal agency that forces disclosure of outcomes. And by outcomes I mean, real outcomes. How many people died? How many people get a clot? How many people get an infection? How many people can function well after whatever is done to them? That’s one thing of what we need.

Once we measure outcomes the health care system will reorganize itself so that it can deliver outcomes. Right now, it can’t make you better for your diabetes, your AIDS, your heart disease. All it can do is optimize the hospital part of that, optimize the doctor part of it, optimize the laboratory part of it.

Anybody who studied systems analysis knows if you optimize all the many little pieces of the system, that’s not the same as optimizing the whole system. A system that measures outcomes will force a change in how health care is delivered. That will make it simultaneously better and cheaper.

Question: How should health insurance be reformed?

Regina Herzlinger: When Harvard University, my brilliant employer, #### health insurance in my behalf, I have zero input into their decision about how they spend my money. I want to have a 100% input into that decision. And there are lots of people who feel the same as I do.

Now, if they want to stay with their employers and have them by their health insurance for them, fine. As for me, give me back my money. Give it to me in the same way that Harvard University can use that money which is tax free, require me to buy health insurance let me go to work on that system. Tens of millions of people like me are going to have the profound impact on health care, that’s consumer-driven health care.

Business involvement in health care should be limited to providing better and more efficient ways of delivering health care, not to act as agents for consumers.

I don’t want my employer to buy my clothes. I don’t want them to buy my food. I don’t want them to buy my car. I don’t want them to buy my house. Not that they’re stupid. But they don’t know what I consider value for the money. I want them out of their health insurance purchase decision.

Question: What are some recent technological advances in health care?

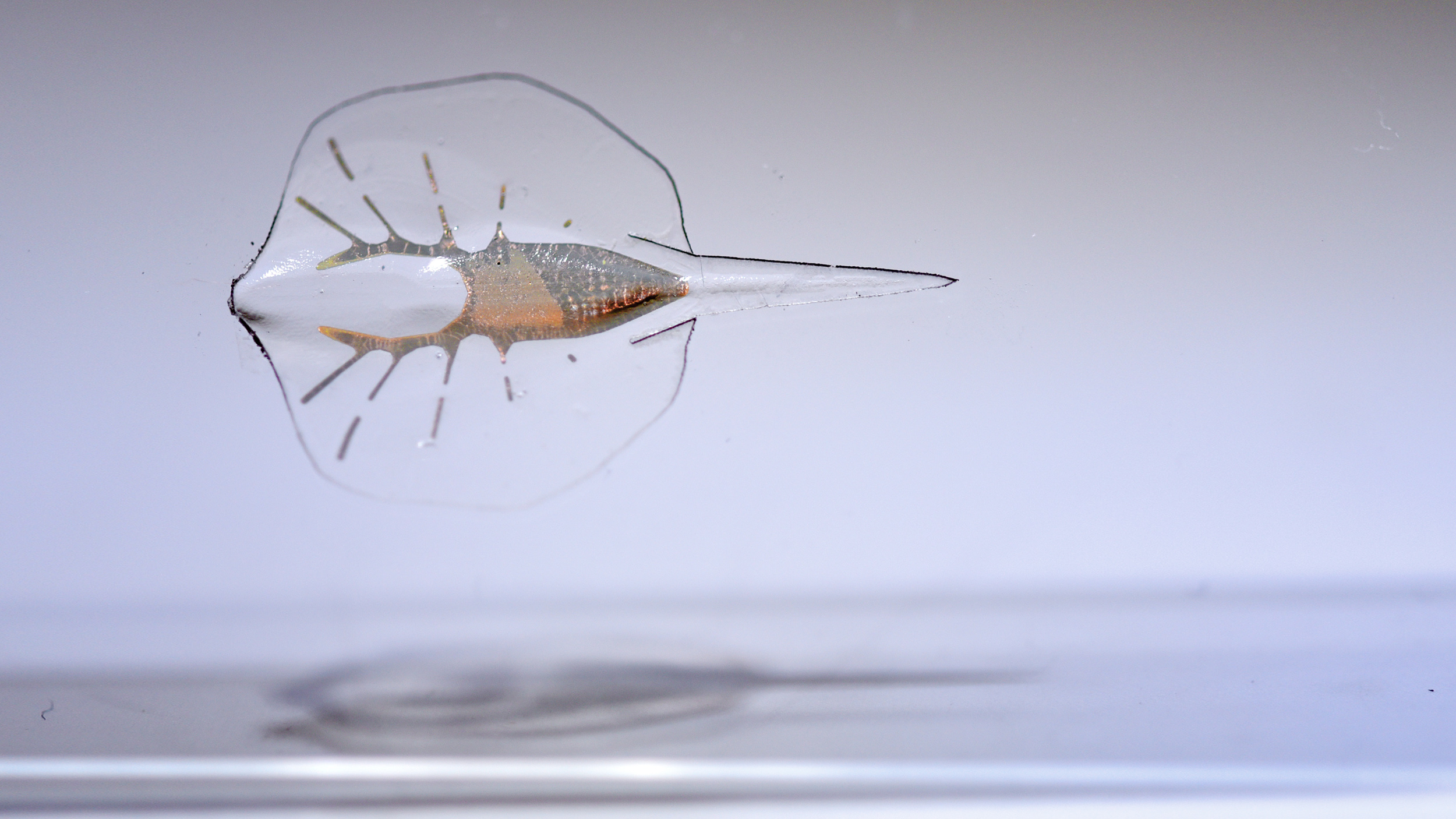

Regina Herzlinger: The other important technological advances are in a field called remote patient monitoring. What this consists of is planting sensors inside the human body that measure what’s going on.

Medtronic, for example, a great medical device company, has a sensor that measures how a heart which suffers from congestive heart failure is so flaccid it can’t pump the fluid in the body. It tells the owner of that heart, “Hey, you’re getting congested. You better take a diuretic.”

Or there’s a little chip that can be embedded on a pill. You swallow the chip, the chip tells you you have too much glucose in your body. That’s very important information for diabetic so that he or she can correct the glucose balance within their bodies.

That is the technological advance. That’s at least as important as the biotechnology advance and what’s typically called personalized medicine.

Electronic medical records are no technological marvel. They’re merely having an electronic record of what happens to you medically.

Why don’t we have those? Why do we have financial records and no electronic medical records? The reason is that our health care system is so fragmented. We have bits and pieces of data with the lab, with the x-ray place, with the various doctors we go to, with the hospitals, with the nursing homes. These people don’t communicate with each other.

The challenge with electronic medical records is not a technological one. It is a managerial one.

How do you line up incentives so that these people start communicating with each other so that the customer can have a complete record of everything that’s been done to them and everything that’s known about them medically?

Question: What are the benefits of the retail medical movement?

Regina Herzlinger: The retail medical movement is very important. One of the main reasons people who have insurance don’t get health care is not that they lack the money, but it’s so darn inconvenient to get to a doctor, to get to an emergency room, to get to a hospital. These retail clinics that are located inside a department store or your local drugstore, they’re the answer to lots of people’s prayers.

Clearly they’re not doing brain surgery in the little clinic in your drugstore. But if your kid has an earache, and you can go the emergency room and sit next to a guy who’s been shot by an Uzi, or you can go to a retail medical clinic, well that’s a pretty easy choice.

Another great thing about these retail medical clinics is they have an innovation in medical care. They tell you what the price is going to be before you actually have the service. They have the price there, $59, $69, so you know what you’re getting in for when you go there.