- Look up—you can see the greatest feat of human cooperation orbiting 254 miles above Earth. As commander of Expedition 35 aboard the International Space Station (ISS), Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield understands the difficulty of cultural barriers in teamwork, and the life or death necessity of learning to communicate across those divides.

- The ISS is a joint project between five space agencies, built by people from 15 different nations—and each of them has a different take on what is “normal”. Hadfield explains the scale of cultural differences aboard the spaceship: “What do you do on a Friday night? What does ‘yes’ mean? What does ‘uh-huh’ mean? What is the day of worship? When do you celebrate a holiday? How do you treat your spouse or your children? How do you treat each other? What is the hierarchy of command? All of those things seem completely clear to you, but you were raised in a specific culture that is actually shared by no one else.”

- Here, Hadfield explains his strategy for genuine listening and communication. Whether it’s money, reputation, or your life that’s at stake, being sensitive and aware of people’s differences helps you accomplish something together—no matter where you’re from.

CHRIS HADFIELD: When we're born, we have a very small view of the world,.our mother's womb and the delivery room. And as you're raised, your parents are probably trying to control the environment that you're in, and so you end up with a very centralized tiny little view of the world, naturally. As you get older, as you travel more, as you read more, you start to understand a little more of the world around you. And all of those influences affect your choices in life. What are you gonna imagine that you could be? If you've never left Main Street, small town Ohio, then you're probably not gonna visualize yourself doing something that is wildly different than that. You're never going to be, uh, the head of a religious sect in, in Pakistan. You know, it's just, it's, it's not inside your worldview. You can only draw your own aspirations and hopes and decisions based on the things that you even know exist.

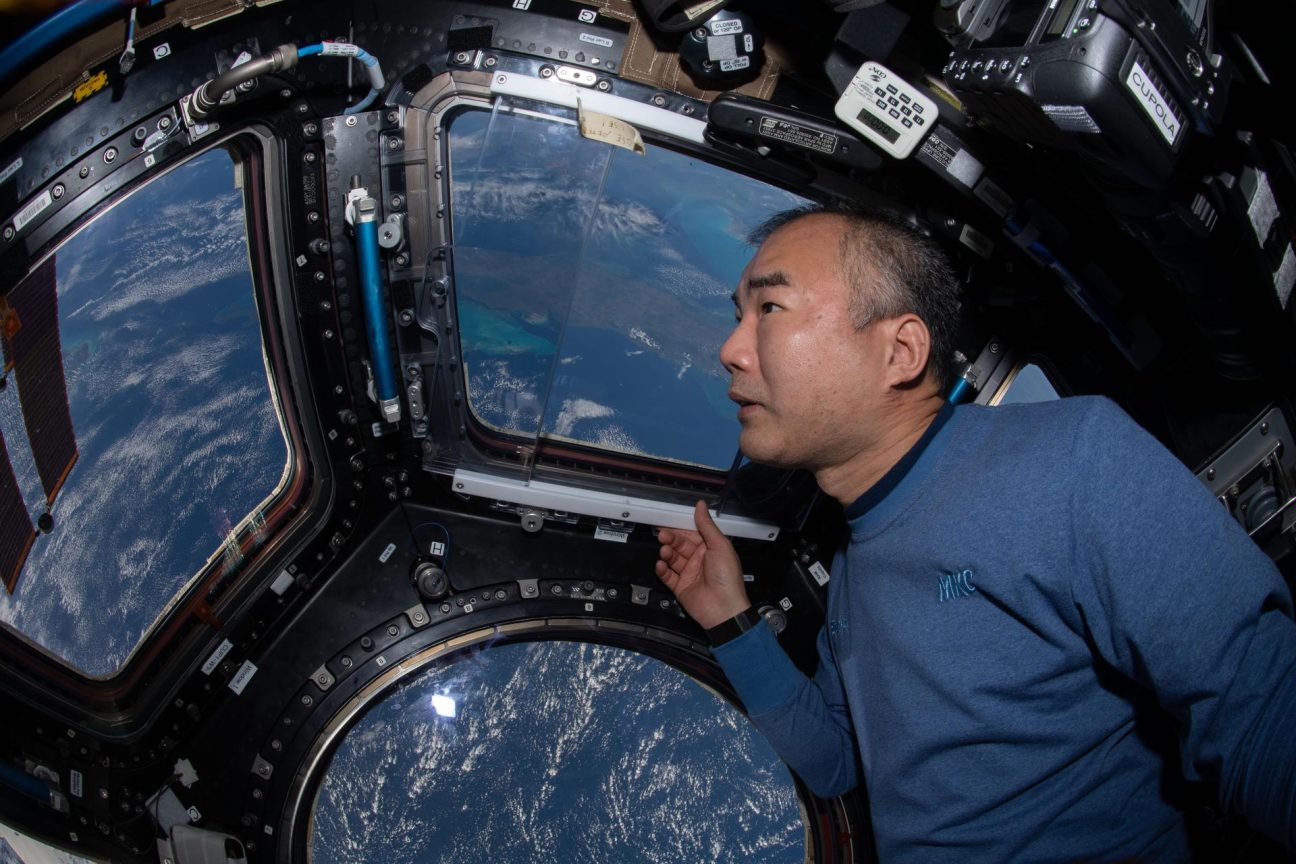

It's easier now to understand and see the world than ever in history. Our ability to communicate and our ability to travel has greatly improved. But space travel is sort of like the, the wildly exaggerated version of that where you can go around the whole world in the time it takes to eat supper and see everywhere, uh, see the whole world 16 times a day. That widens and deepens your worldview like nothing we've ever seen before in history. And it's very difficult to maintain, um, artificially drawn biases like, like nationalistic borders and, you know, my little tribe, my little street, my little gang, my little town, my little whatever when 15 minutes later you're over at the exact the same looking sort of town, but it's in Africa. And 40 minutes later the exact same looking sort of town and it's in Australia.

And then you come to Indonesia and you go, " Man, it's, it's all the same." They build the towns just like we build our towns. And, and what's, how, how are they, they then? It's just sort of all us. We're all doing this thing together, and everyone's got the same sort of hopes and dreams amongst themselves. And that pervasive sense of the shared collective experience of being a human being, that seeps into you on board a spaceship. Not the first time around. The first time is overwhelming. But somewhere, you know, 100 times around, 500 times around, suddenly, uh, the world becomes one place in your mind. It's not very big and, uh, and that, I think, is a really important worldview to have.

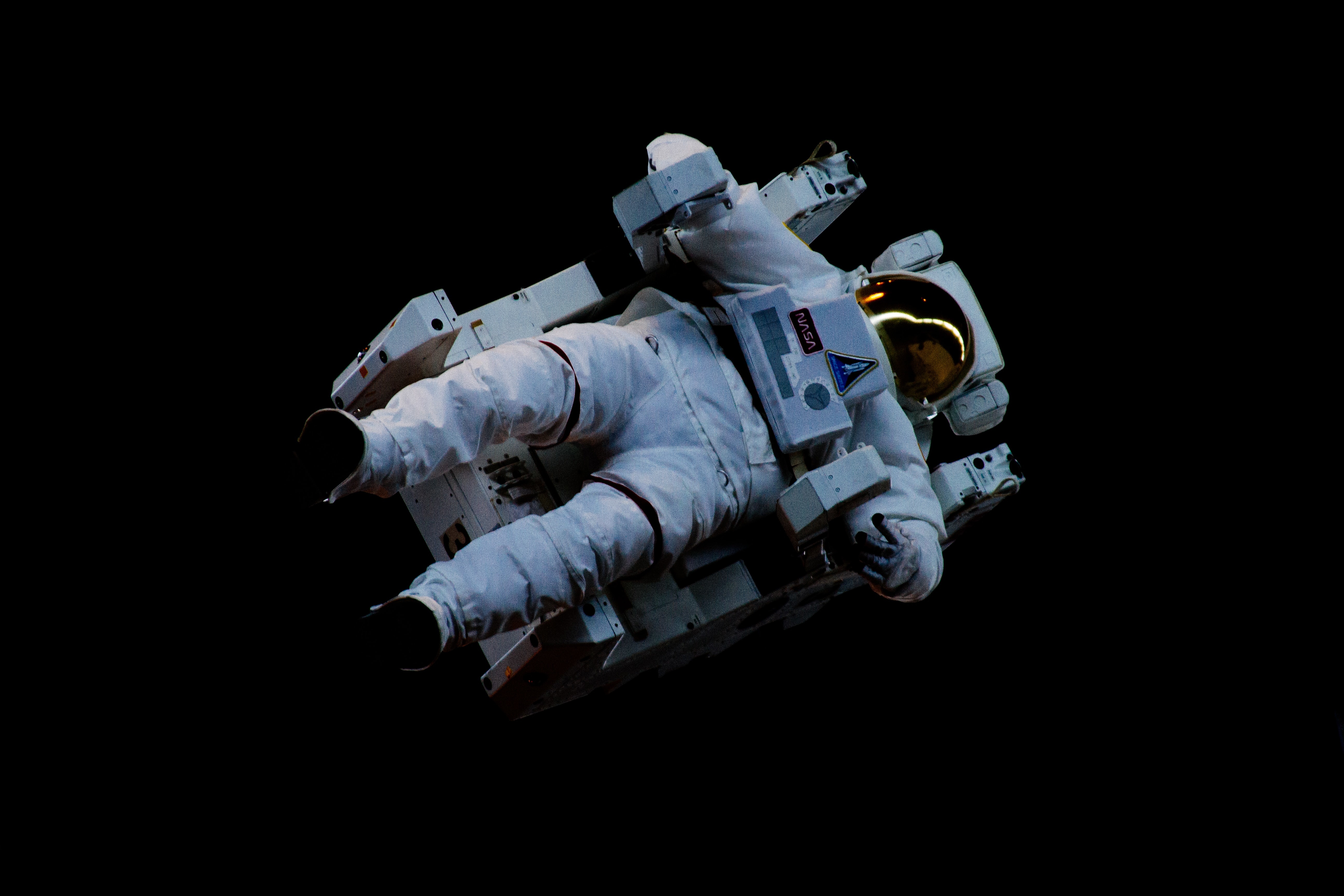

Life can be full of magnificent experiences. You know, um, being at the wedding of a loved one in a beautiful big house of worship somewhere, where there's the sound and the beauty and the structure, it affects how you feel that day. And, and you act a little bit differently. Or walking into a gigantic ancient redwood forest. Your, your head is naturally drawn upwards and, and you think a little different. It's not the same as just walking down your street. Well, imagine what it's like on spaceship where you're floating weightless at a window where you see an entire continent in, in the time it takes to drink a cup of coffee, where you go from L.A. to New York in nine minutes. And you see all of that history, and culture, and climate, and geography, and geology, and it's all right there underneath you. And you see a sunrise or a sunset every 45 minutes. You see the world for what it actually is. It has that same sort of, uh, personal effect you of a feeling of privilege and sort of a reverence, an awe that, uh, that is pervasive.

When we're floating in the, in the, the bulging window, the cupola of the space station, normally it's just one person 'cause everybody's busy. But if there's two of you in there, you talk in hushed tones to each other just because you feel like you're just wildly lucky to even be there to see this happening. And that sense of wonder, and privilege, and clarity of the world slowly shifts your view, of course. Your understanding of what is us and what is them? Um, what is old and what is new? What does four billion years actually mean? You know, where you can see where the ice ages were. You can see where the volcanoes were and the huge asteroid impacts and such. And it all starts to sort of shift in your head.

There was a fellow in the late '60s, early '70s who wrote a book sort of trying to capture that. He called it the overview effect. You can call it whatever you like. It doesn't have to be involved with space flight. It's more when you sense that there is something so much bigger than you, so much more, uh, deep than you are, ancient, um, has sort of a, a natural importance that dwarfs your own. But you're a person seeing it. You're a person that's interpreting it. You're, you're understanding it in your own way, and you'd have to be a stone to not have that affect you. It, it's, it changes how you think about things. But it's not the same for everybody and it's not instantaneous. It's not, it's not like, "Hey, I've gone over 60 miles an hour. I'm, you know, now done this thing." It's, it's very much a gradual creeping improvement in perception of the world around us. I think that's what the author was trying to talk about when, when he wrote about the overview effect.

Um, and some people are much more emotive and it affects them very deeply. Some people, they just have a better understanding of the world itself. Either way, it's healthy. It's a perspective of the world that allows us, hopefully, to make better collective global decisions about what's happening, less jealous, narrow, local decisions. And we need that type thinking if, if we're truly gonna have this many people and this standard of living for, for the foreseeable future. We just need to see the world as one place, the fact that we're all in this together, and that we are in the position to actually understand it and, and appreciate it, and therefore make different decisions about it.