The Christian church so holy that Muslims hold its keys

Credit: Emmanuel Dunand via AFP / Getty Images

- The Church of the Holy Sepulcher is not just the holiest site in Christianity; it is also emblematic of the religion's deep divisions.

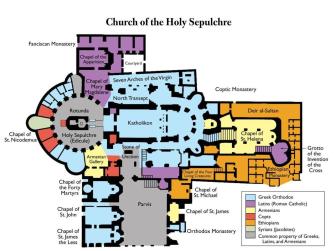

- As the map below shows, six denominations each control part of the church, with only some parts held in common.

- Each "territory" is jealously guarded and sometimes fought over. The church's keys are held by… two Muslim families.

On a ledge over a church door in Jerusalem stands a simple cedarwood ladder. It’s been there for perhaps three centuries. Since nobody remembers who put it there, nobody knows who is authorized to remove it. If anyone would try, there’d be immediate trouble with whomever would feel slighted — and there are plenty of candidates. This is the Immovable Ladder, and it is a fitting symbol for the deeply-entrenched divisions within Christianity, and within that church building itself.

The most sacred place on Earth

Those religious divides matter here more than anywhere else because this is the most significant church in the world. For Christians of any denomination this is the most sacred place on Earth. This is the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, and according to tradition, it contains both Golgotha (or Calvary in Latin; both mean “skull”), the place where Jesus died on the cross. Just a few feet further is the tomb (a.k.a. sepulcher) where his body was laid to rest and where according to the faithful he was resurrected three days later.

Yet despite its supreme religious importance, there is no single authority managing this holiest of church buildings. The care over the sprawling, multi-level complex is divided between various denominations.

The church’s history goes back to the fourth century, when Roman emperor Constantine, newly converted to Christianity, sent his mother Helena to Jerusalem to locate places and things associated with the life and death of Jesus. This is the spot where she found the True Cross, a sign that this must have been Golgotha. The place of Jesus’ burial was identified nearby. Constantine razed the pagan temple built here by his predecessor Hadrian, and a church on this spot, the first commissioned by a Roman emperor, was consecrated in the year 335.

In continuous use for 1700 years

The church has survived earthquakes, fires, invasions, and demolition by decree. It has been in continuous use for nearly 1700 years, even if the building standing there today is mostly a renovation and reconstruction dating to Crusader times. Over the centuries, various Christian traditions latched on to the church. Ownership became a constant source of dispute.

In 1852, the Ottoman Sultan decreed that the church was to be managed by the Greek Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Armenian Apostolic churches and apportioned parts of the building to each denomination. Over time, smaller parts of the building came under the authority of three smaller Orthodox denominations: the Coptic, Syriac, and Ethiopian churches.

- Most of the building is under control of the Greek Orthodox church (in blue on the map). They manage the Katholikon (which is slightly ironic), the North Transept, the Seven Arches of the Virgin, a small Orthodox monastery, and various chapels, among other bits.

- The Latins (a.k.a. Roman Catholics, in purple) manage the Franciscan Monastery on the north side (which includes the Chapel of the Apparition and the Chapel of Mary Magdalene), the Grotto of the Invention of the Cross, a small area north of the Parvis, and a tiny space between the Katholikon and the Rotunda.

- The Armenians (in yellow) manage the Chapel of St. Helena, the Chapel of St. James, and the Armenian Gallery next to the Rotunda.

- The Copts (in red) have the care of various chapels near the Rotunda, including a small annex to the Edicule (i.e., the Holy Sepulcher) itself.

- The Ethiopian monastery is spread out on the roof, and the Ethiopians also manage an area called Deir al-Sultan, the Chapel of the Four Living Creatures, and the Chapel of St. Michael (all in orange).

- The Syriac church has the smallest part (in green): the Chapel of St. Nicodemus. But at least it’s very close to the Sepulcher.

The Ottoman edict is the basis for the status quo, which is scrupulously maintained. A complex set of rules determines how the church is managed — such as who is allowed where and when, who cleans and repairs which parts of the building, and which areas are held in common (by the Greeks, Latins, and Armenians but not by the other three).

- The Rotunda is common territory, as is a chapel to the north.

- The Parvis (i.e. the courtyard at the entrance) is also common, as is an adjacent part of the church that contains the Stone of Unction (where according to tradition, Jesus’ body was prepared for burial).

But some of the rules are disputed, and conflicts occasionally erupt. Two examples:

- The Copts have a long-standing claim over part of the roof, which is occupied by Ethiopian monks. To maintain their claim, Coptic monks take turns to sit on a chair on the roof. But on a particularly hot day in 2002, when a Coptic monk moved the chair a few inches into the shade, the Ethiopians interpreted that move as a violation of the status quo. The ensuing fight sent 11 monks to the hospital.

- And in 2008, Greek and Armenian monks got into a violent argument over the procedure of a religious procession. The brawl was caught on camera and pasted all over the news.

Can’t we all just get along?

In recent years, however, the churches seem to be getting along a little bit better, although partly out of necessity. Significant parts of the building are in extreme need of repair. In 2017, the three main denominations (Catholic, Greek, and Armenian) agreed to fix the Edicule, which was in danger of collapsing. And in 2019, the three churches signed an agreement to renovate parts of the church’s infrastructure (floor, foundations, and sewage pipes) and even to share ownership of any archaeological artifacts that might turn up during the work. However, the agreement excludes the three other denominations, which under the status quo have no say in the management of shared spaces.

Which brings us back to the Immovable Ladder. Despite its nickname, it has proven to be very movable indeed. It was stolen twice in the 20th century. Both times, it was soon recovered by the police and returned to its original position. In 2009, it was moved again, this time with the agreement of all relevant denominations, in order to accommodate scaffolding for renovations.

Upon completion of the works, it was again put back. And there it will remain until, as Pope Paul VI suggested in 1964, the divisions between the various Christian denominations are resolved. Or until Christ returns — whichever happens first.

Meanwhile, the keys to the church building itself will remain where they have been for centuries: in the possession of the Joudeh and Nuseibeh families, who by virtue of their Muslim faith are accepted by all Christian denominations as neutral guardians of the entrance to the church.

Strange Maps #1081

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].