A technique to sift out the universe’s first gravitational waves

Photo by Denis Degioanni on Unsplash

In the moments immediately following the Big Bang, the very first gravitational waves rang out.

The product of quantum fluctuations in the new soup of primordial matter, these earliest ripples through the fabric of space-time were quickly amplified by inflationary processes that drove the universe to explosively expand.

Primordial gravitational waves, produced nearly 13.8 billion years ago, still echo through the universe today. But they are drowned out by the crackle of gravitational waves produced by more recent events, such as colliding black holes and neutron stars.

Now a team led by an MIT graduate student has developed a method to tease out the very faint signals of primordial ripples from gravitational-wave data. Their results were published in December 2020 in Physical Review Letters.

Gravitational waves are being detected on an almost daily basis by LIGO and other gravitational-wave detectors, but primordial gravitational signals are several orders of magnitude fainter than what these detectors can register. It’s expected that the next generation of detectors will be sensitive enough to pick up these earliest ripples.

In the next decade, as more sensitive instruments come online, the new method could be applied to dig up hidden signals of the universe’s first gravitational waves. The pattern and properties of these primordial waves could then reveal clues about the early universe, such as the conditions that drove inflation.

“If the strength of the primordial signal is within the range of what next-generation detectors can detect, which it might be, then it would be a matter of more or less just turning the crank on the data, using this method we’ve developed,” says Sylvia Biscoveanu, a graduate student in MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research. “These primordial gravitational waves can then tell us about processes in the early universe that are otherwise impossible to probe.”

Biscoveanu’s co-authors are Colm Talbot of Caltech, and Eric Thrane and Rory Smith of Monash University.

A concert hum

The hunt for primordial gravitational waves has concentrated mainly on the cosmic microwave background, or CMB, which is thought to be radiation that is leftover from the Big Bang. Today this radiation permeates the universe as energy that is most visible in the microwave band of the electromagnetic spectrum. Scientists believe that when primordial gravitational waves rippled out, they left an imprint on the CMB, in the form of B-modes, a type of subtle polarization pattern.

Physicists have looked for signs of B-modes, most famously with the BICEP Array, a series of experiments including BICEP2, which in 2014 scientists believed had detected B-modes. The signal turned out to be due to galactic dust, however.

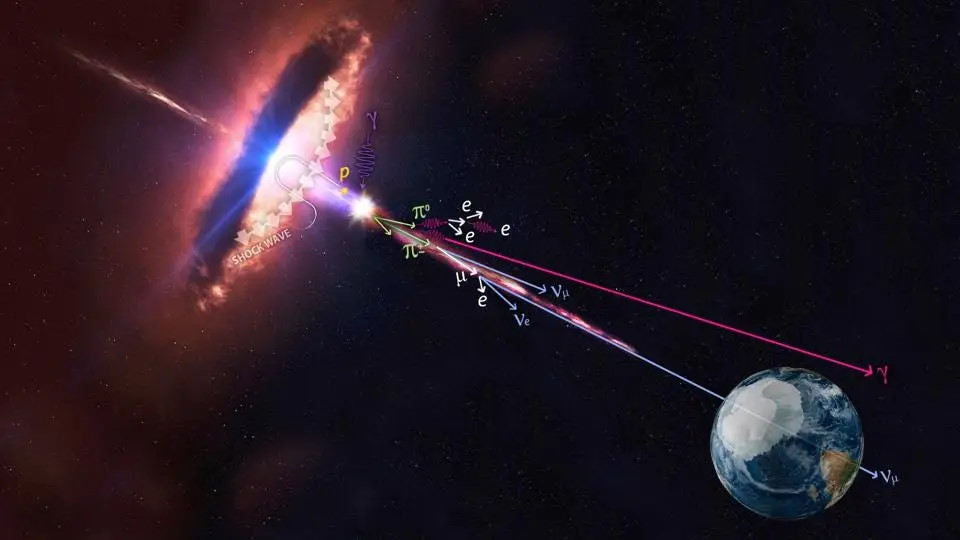

As scientists continue to look for primordial gravitational waves in the CMB, others are hunting the ripples directly in gravitational-wave data. The general idea has been to try and subtract away the “astrophysical foreground” — any gravitational-wave signal that arises from an astrophysical source, such as colliding black holes, neutron stars, and exploding supernovae. Only after subtracting this astrophysical foreground can physicists get an estimate of the quieter, nonastrophysical signals that may contain primordial waves.

The problem with these methods, Biscoveanu says, is that the astrophysical foreground contains weaker signals, for instance from farther-off mergers, that are too faint to discern and difficult to estimate in the final subtraction.

“The analogy I like to make is, if you’re at a rock concert, the primordial background is like the hum of the lights on stage, and the astrophysical foreground is like all the conversations of all the people around you,” Biscoveanu explains. “You can subtract out the individual conversations up to a certain distance, but then the ones that are really far away or really faint are still happening, but you can’t distinguish them. When you go to measure how loud the stagelights are humming, you’ll get this contamination from these extra conversations that you can’t get rid of because you can’t actually tease them out.”

A primordial injection

For their new approach, the researchers relied on a model to describe the more obvious “conversations” of the astrophysical foreground. The model predicts the pattern of gravitational wave signals that would be produced by the merging of astrophysical objects of different masses and spins. The team used this model to create simulated data of gravitational wave patterns, of both strong and weak astrophysical sources such as merging black holes.

The team then tried to characterize every astrophysical signal lurking in these simulated data, for instance to identify the masses and spins of binary black holes. As is, these parameters are easier to identify for louder signals, and only weakly constrained for the softest signals. While previous methods only use a “best guess” for the parameters of each signal in order to subtract it out of the data, the new method accounts for the uncertainty in each pattern characterization, and is thus able to discern the presence of the weakest signals, even if they are not well-characterized. Biscoveanu says this ability to quantify uncertainty helps the researchers to avoid any bias in their measurement of the primordial background.

Once they identified such distinct, nonrandom patterns in gravitational-wave data, they were left with more random primordial gravitational-wave signals and instrumental noise specific to each detector.

Primordial gravitational waves are believed to permeate the universe as a diffuse, persistent hum, which the researchers hypothesized should look the same, and thus be correlated, in any two detectors.

In contrast, the rest of the random noise received in a detector should be specific to that detector, and uncorrelated with other detectors. For instance, noise generated from nearby traffic should be different depending on the location of a given detector. By comparing the data in two detectors after accounting for the model-dependent astrophysical sources, the parameters of the primordial background could be teased out.

The researchers tested the new method by first simulating 400 seconds of gravitational-wave data, which they scattered with wave patterns representing astrophysical sources such as merging black holes. They also injected a signal throughout the data, similar to the persistent hum of a primordial gravitational wave.

They then split this data into four-second segments and applied their method to each segment, to see if they could accurately identify any black hole mergers as well as the pattern of the wave that they injected. After analyzing each segment of data over many simulation runs, and under varying initial conditions, they were successful in extracting the buried, primordial background.

“We were able to fit both the foreground and the background at the same time, so the background signal we get isn’t contaminated by the residual foreground,” Biscoveanu says.

She hopes that once more sensitive, next-generation detectors come online, the new method can be used to cross-correlate and analyze data from two different detectors, to sift out the primordial signal. Then, scientists may have a useful thread they can trace back to the conditions of the early universe.

Reprinted with permission of MIT News. Read the original article.