The Least Likely Record To Fall This Olympics, And Beyond

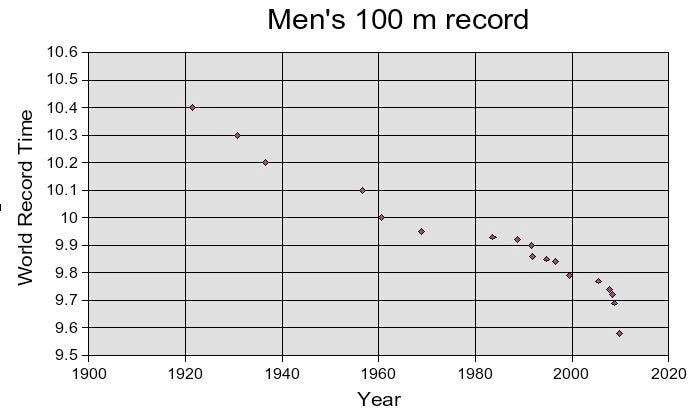

If you thought Usain Bolt’s 9.58s world record time in the 100 meters was ever in jeopardy, this shows how unlikely that was.

“A lot of legends, a lot of people, have come before me. But this is my time.” -Usain Bolt

Sunday, August 14th: the two-time defending gold medalist and world record holder in the men’s 100 meters, Usain Bolt, steps to the starting line. He’s won six olympic gold medals — the 100m, 200m, and 4x100m relay in 2008 and 2012 apiece — and current holds the record in all three events at 9.58s, 19.19s and 36.84s. He’s won three 100m world championships, at the 2009 events in Berlin (where he set the all-time record), and again in 2013 and 2015. He owns the three fastest times in 100m history: 9.58s, 9.63s and 9.69s (which two others have tied), and has never tested positive for doping, unlike his closest American rivals, Tyson Gay and Justin Gatlin. This Olympics, at the age of 29, he faces off against his closest rivals, including Gatlin, teammate Yohan Blake and a new crop of young superstars, all capable of sub-10s times.

And no one touches the world record.

“How did you know that?” There’s a reason we run these races in the first place, after all. At the 1991 world championships, what most people considered to be a past-his-prime Carl Lewis stepped to the line in the 100m finals against the record holder, Leroy Burrell, and the strongest field of sprinters ever assembled. Lewis himself was a decorated former world record holder, having won Olympic gold and set world records in the event 1984 and 1988 (once Ben Johnson was stripped after a positive steroid test), but had never broken the 9.9s barrier. At the age of 30, many wrote Lewis off, with some calling him washed-up. Yet he ran the race of his life, finishing in 9.86s and setting the world record in the process.

That world record would progress many times over the next few years. Burrell would re-take the record in 1994 with a run of 9.85s, Donovan Bailey would shave the time down to 9.84s in 1996, Maurice Green would improve that to 9.79s in 1999, breaking the 9.8s barrier. Then in 2005, Asafa Powell burst onto the scene, breaking the record with a time of 9.77s, eventually improving that down to 9.74s in 2007, just before the Beijing Olympics. But Bolt’s 9.69s in the 2008 Olympic finals has never been beaten, except by Bolt himself, with his 9.58s time in the 2009 world championship finals and his 9.63s in the 2012 Olympic finals.

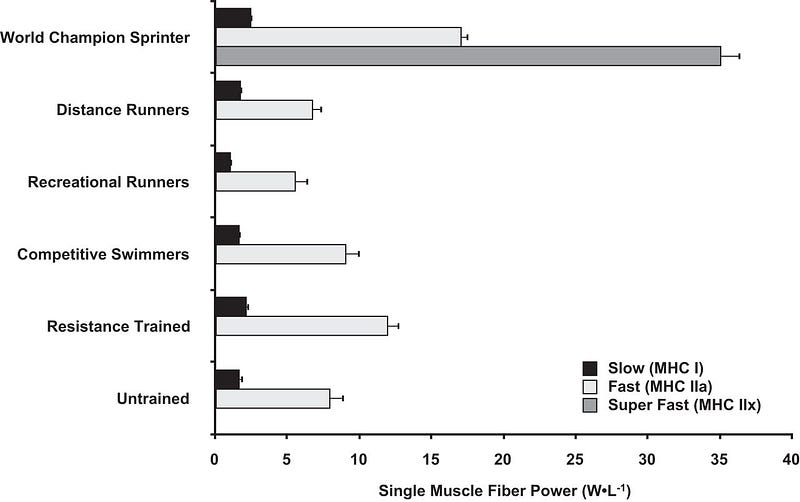

With a number of runners hovering around the 9.7s mark, how can we be so sure that Bolt’s 9.59s won’t be challenged again so soon? While you can never be sure, the progression of world records in running events often follows a simple mathematical formula. In the early eras, the record progresses at a roughly steady rate — appearing to follow a straight line — as training, technique, equipment and overall physiques improve steadily. As time moves forward, progress typically occurs in small increments, as human beings find it more difficult to make progress towards such an elusive goal. Bolt himself may be an outlier in a number of aspects, but he’s certainly within the realm of what’s humanly possible. But physically, there’s going to be an overall limit: not of an infinitely fast time, but of a time that’s fundamentally limited by the physiology of the human body.

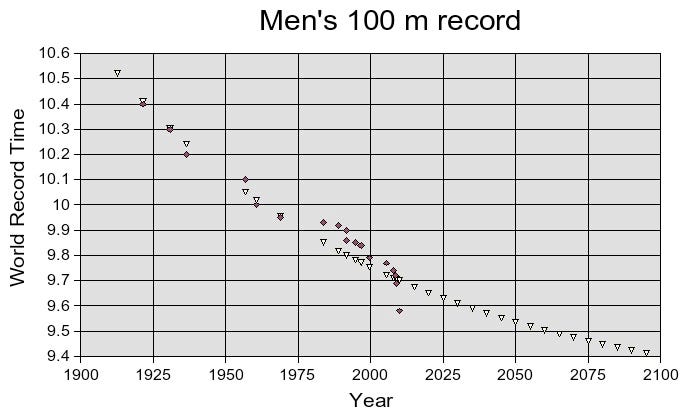

There’s a mathematical curve we can fit to the world record progression that encapsulates all of that behavior as simply as possible: by modeling that with an exponential function. In general, you want the number of parameters in your model to be as small as possible, and it must be significantly smaller than the number of data points you have to fit it to. An exponential curve is the simplest, fewest-parameter model (only 3) that captures all of the relevant behavior we discussed. And compared to those three parameters, we have 19 data points to go on.

There are a few incredible things to learn from this:

- The ultimate time that human males should be able to reach in the 100m dash is somewhere around the 9.2s mark, based on their performance to date.

- Bolt’s 9.58s time is such an outlier that we wouldn’t expect athletes to achieve it again until the late 2030s or early 2040s, following this progression.

- And that Bolt’s very existence has changed what we think humanity’s limits are. Without him, our limits would appear to be more than a tenth of a second slower.

All of this is even more remarkable when you consider that all of Bolt’s nearest competitors — Gay, Blake, Gatlin and Powell — have been banned or suspended at least once for doping violations, while Bolt has never ever failed a drug test.

Predicting how this trend will continue in the future is a difficult task, and no simple model is every going to encapsulate the full capabilities of the human body over time with just three parameters. But even a simple analysis like this shows that Bolt is a generation ahead of his time. No one has ever won gold in the 100m, 200m and 4x100m relay in two consecutive Olympics — much less three — like Bolt has. I’d be very surprised if Bolt broke his own record before he retires, but I’d be even more shocked if anyone else came close to challenging it. As Olympic champion Michael Johnson put it, a runner capable of surpassing Bolt’s time “hasn’t been born yet.”

This post first appeared at Forbes, and is brought to you ad-free by our Patreon supporters. Comment on our forum, & buy our first book: Beyond The Galaxy!