Is life possible on Mars?

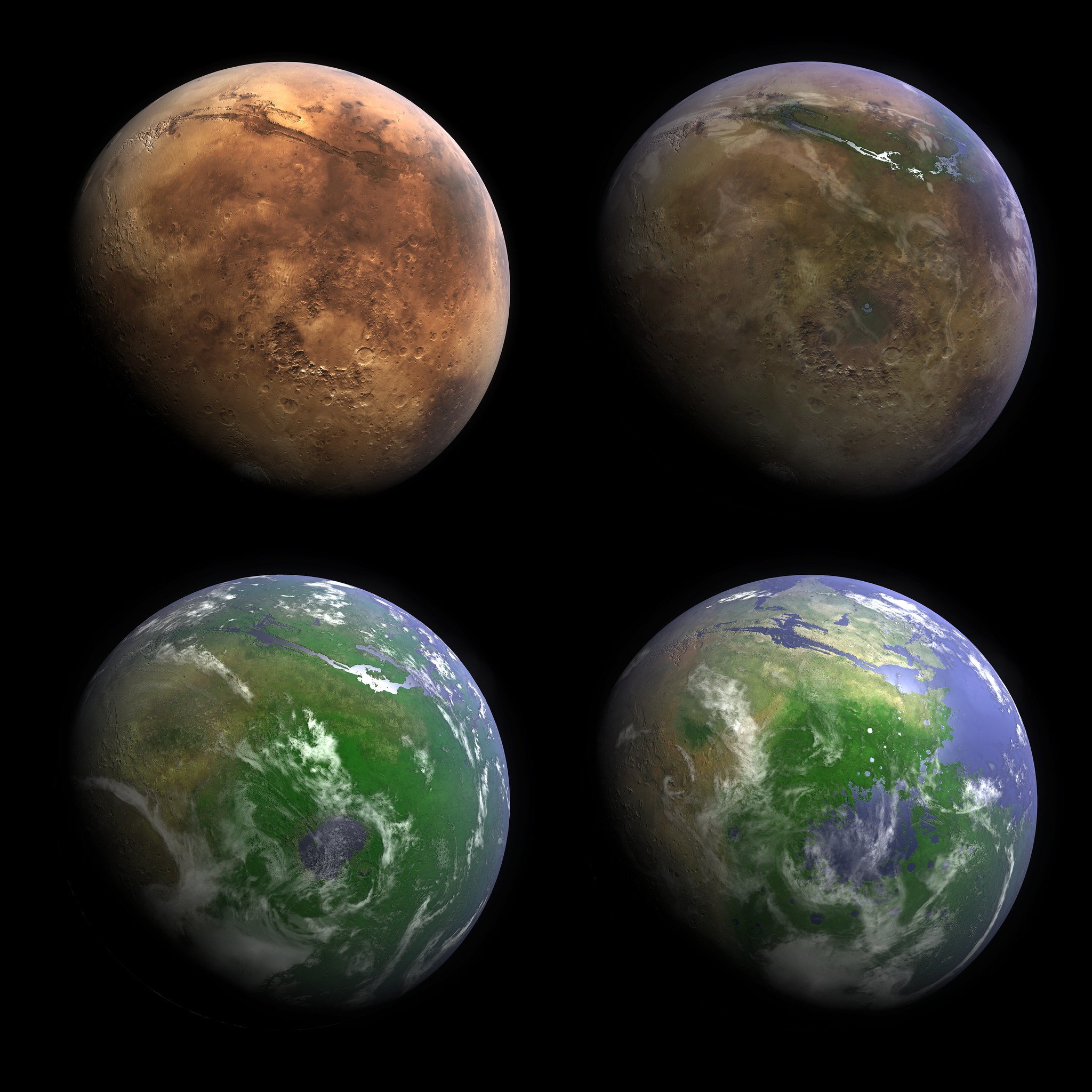

- We know Mars was once wet, with oceans, continents, and a thick atmosphere. Could life have once been ubiquitous there, too?

- If Mars was alive, could that life persist today? Is it active, dormant, or extinct? And where did it originate: on Mars, on Earth, or even elsewhere?

- Overall, there are 5 distinct possibilities for the history of life on Mars. Despite the intriguing possibilities, we lack decisive evidence for all of them.

For as long as humanity has been watching the skies, we’ve been fascinated with the possibility that other worlds — much like Earth — might contain living organisms. While our visits to the Moon taught us that it’s completely barren and uninhabited, other worlds within our Solar System remain full of potential. Venus might have life in its cloud-tops. Europa and Enceladus might have life teeming in a sub-surface ocean of liquid water. Even Titan’s liquid hydrocarbon lakes provide a fascinating place to search for exotic living organisms.

But by far, the most fascinating possibility is the red planet: Mars. This smaller, colder, more distant cousin of Earth most certainly had a wet past, where liquid water clearly flowed on the surface for more than a billion years. Circumstantial evidence has pointed to the plausibility of life on Mars, not only in the ancient past, but possibly still living, and perhaps occasionally active, even today. There are five possibilities for life on Mars. Here’s what we know so far.

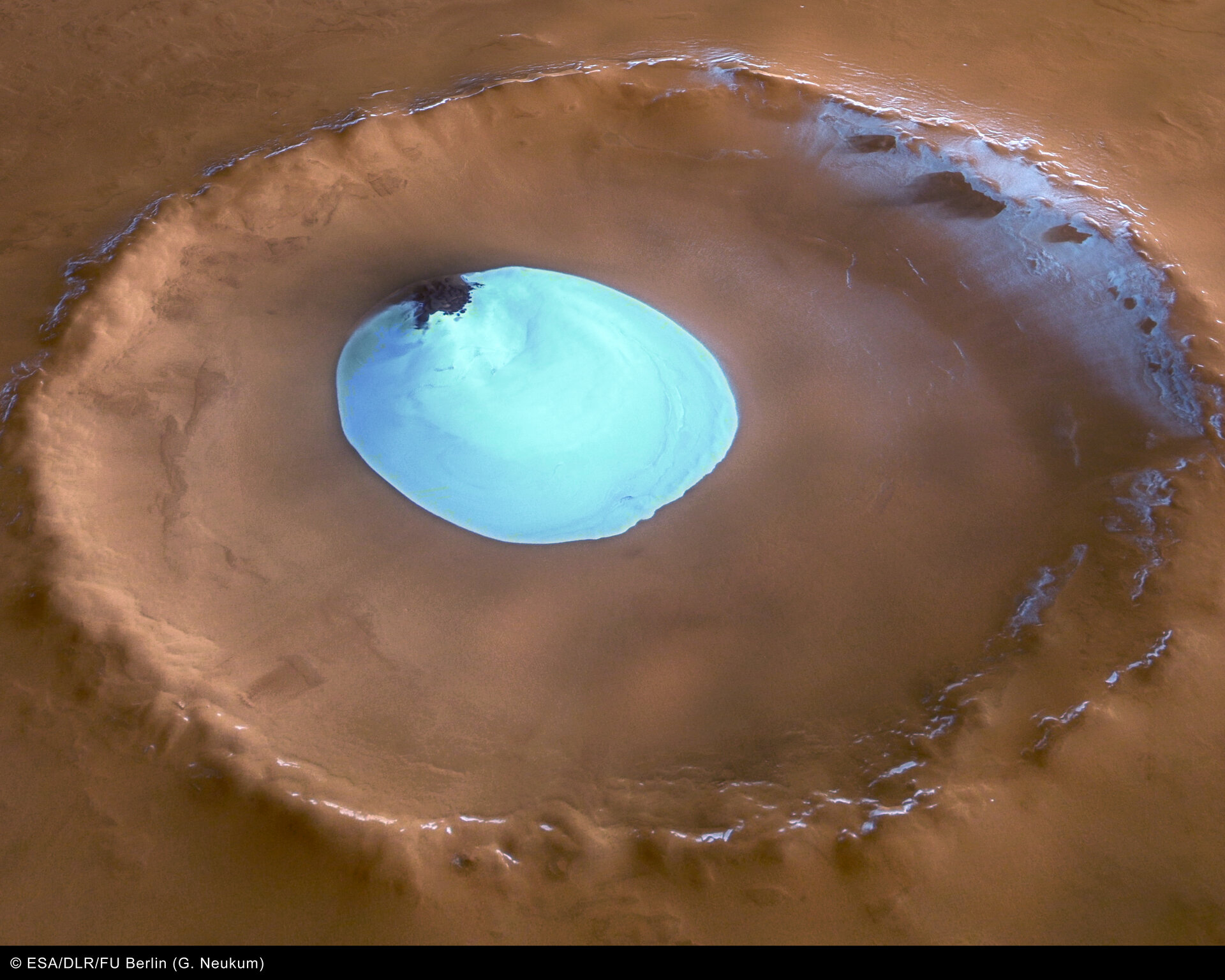

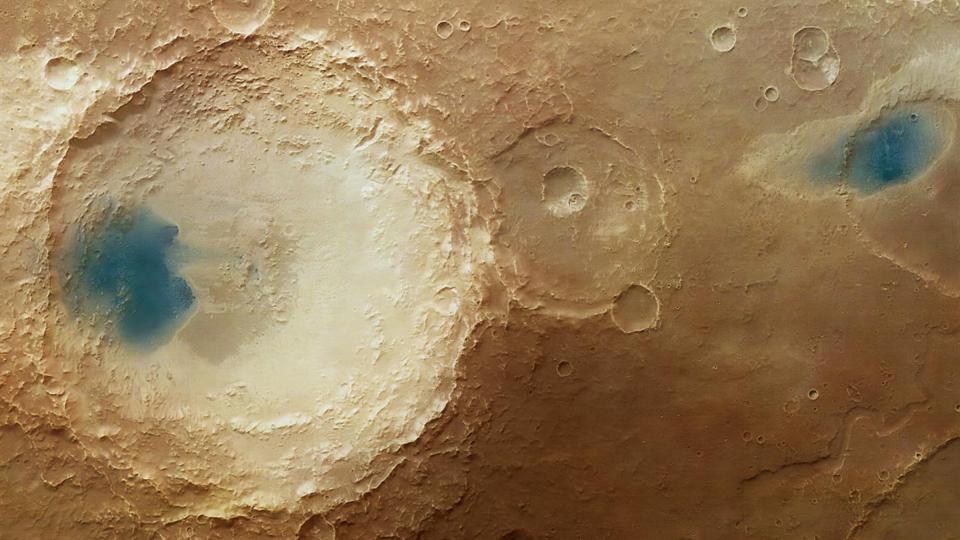

With the information we’ve obtained from various orbiters, landers, and rovers, we’ve made a slew of fascinating discoveries on Mars. We see dried-up riverbeds and evidence of ancient glacial events on the Martian surface. We find tiny hematite spheres on Mars as well as copious evidence for sedimentary rock, both of which only form on Earth in aqueous environments. And we’ve observed solid sub-surface ice, snows, and even frozen surface water on Mars in real-time.

We’ve even observed what’s likely to be briny surface water actively flowing down the walls of various craters, although that result is still controversial. All the raw ingredients that are required for life on Earth were abundant on early Mars as well, including a thick atmosphere and liquid water on its surface. Although Mars no longer appears as though it’s teeming with life today, there are three pieces of evidence that past or even present life might be a possibility.

The first compelling piece of evidence came from the instruments on board NASA’s Mars Viking landers in 1976. Three biology experiments were performed: a gas exchange experiment, a labeled release experiment, and a pyrolytic release experiment, followed-up by a gas chromatograph mass spectrometer experiment. The labeled release experiment yielded a positive result when performed on both Viking landers, but only the first time the test occurred. All other experiments came back negative.

The second piece of evidence came when a fragment of a Martian meteorite — Allan Hills 84001 — was recovered on December 27, 1984. As it turns out, approximately 3% of all meteorites that fall to Earth originate from Mars, but this one was particularly large: nearly 2 kilograms (over 4 pounds) heavy. It originally formed on Mars some 4 billion years ago, and landed on Earth only some 13,000 years ago. When we looked inside of it in 1996, it appears to contain material that could be the remnants of fossilized organic life forms, although the nature of the inclusions are ambiguous; they could have arisen from inorganic processes as well.

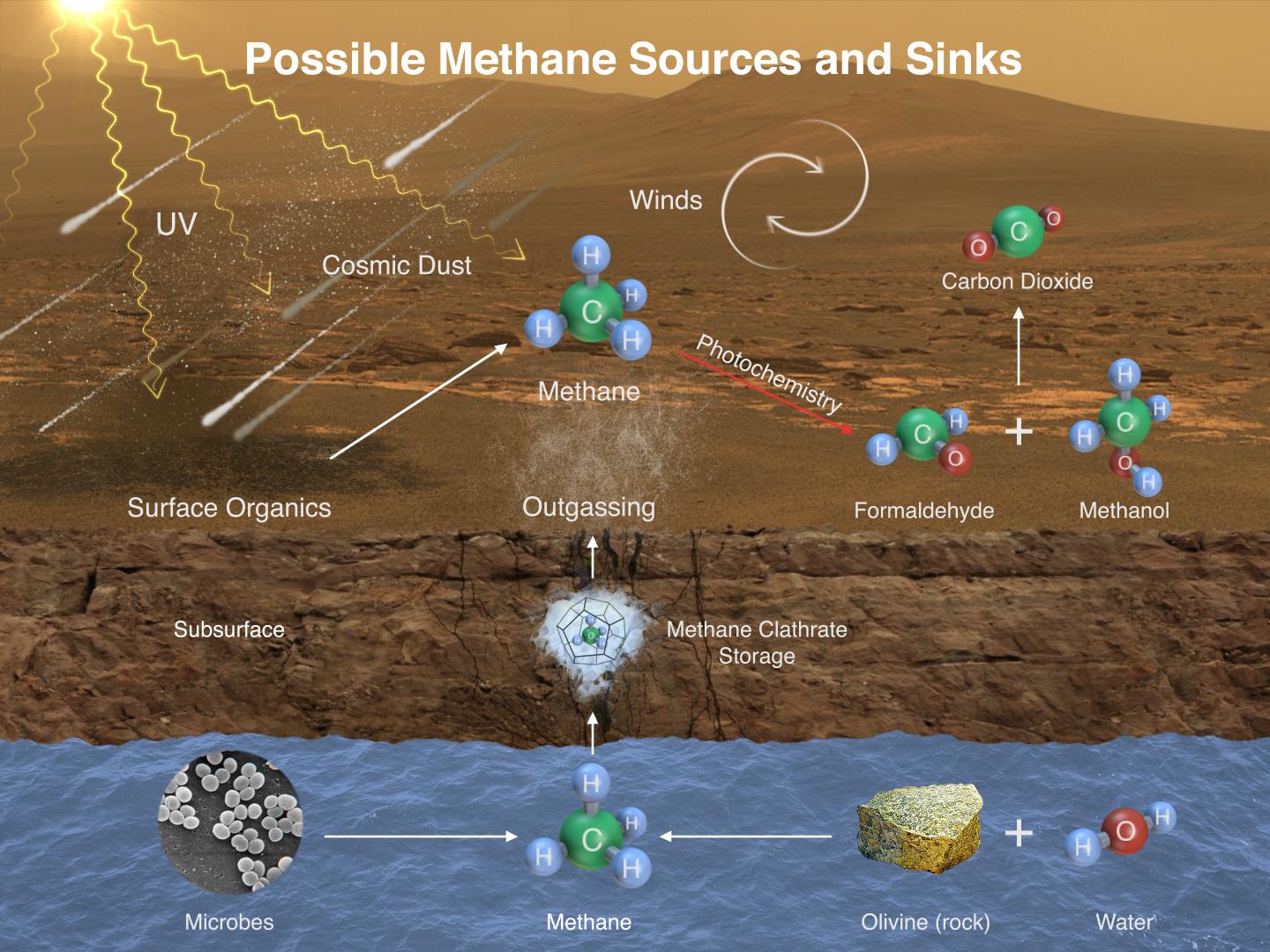

And finally, the third piece of evidence came out with NASA’s 2010s-era Mars rover: Curiosity. As the seasons changed on Mars, Curiosity detected “burps” of methane emitted from specific underground locations, but only at the end of Martian winter and with the onset of spring. This is, again, an ambiguous signal at best, as inorganic, geochemical processes could be seasonal and result in the release of methane, but organic, biological processes could cause this as well.

When we look at the full suite of evidence — at everything we’ve learned about Mars — there are five possibilities for the history of life on the Red Planet.

- It could be an eternally barren world.

- It could be a world where life thrived for a time but then hit a dead-end.

- It could have extant life on it today.

- It could have been seeded by Earth-based life early on.

- Or it could only have Earth-based organisms that made their way there since the dawn of the space age.

Here’s what each possibility would mean.

1.) Mars never had life on it. Despite having the same raw ingredients as early Earth and similar, watery conditions, the necessary circumstances that enable life to form simply never occurred on Mars. All the geological and chemical processes that occur inorganically still happened, but nothing organic. Then, a little more than three billion years ago, Mars’s atmosphere was stripped away by the Sun, drying up any liquid surface water and leading to Mars’s current appearance.

This is the most conservative stance, and would require that all three of the purported “positive” tests have either an inorganic or contamination-based resolution. This is eminently possible, and remains — in the mind of many — the default assumption. Until some very compelling evidence comes along that robustly points to either past or present life on Mars, this will likely remain the leading hypothesis.

2.) Mars had life early on, but it died out. This scenario, in many ways, is just as compelling as the prior one. It’s very easy to imagine that a world with:

- a thick atmosphere similar to early Earth’s,

- stable, liquid water on its surface,

- continents with rich geological diversity,

- volcanoes,

- a magnetic field,

- a day similar in length to our own,

- and temperatures only marginally cooler than Earth’s today,

could lead to life. To many, it’s virtually impossible to imagine that these conditions — after more than a billion years — wouldn’t lead to life, considering that life arose on Earth no more than a few hundred million years after its formation.

However, the loss of the Martian atmosphere had a profound effect on the planet, and could have resulted in the extinction of all life on Mars. Drilling down into the sedimentary rock of Mars and searching for fossilized life forms, or even metamorphosed carbon-rich inclusions, could potentially reveal the evidence necessary to validate this scenario.

3.) Mars had early life, and it still persists in a mostly-dormant form beneath the surface. This is the most optimistic, but still scientifically viable, view of life on Mars. Perhaps life took hold early on, and when Mars lost its atmosphere, a few extremophiles remained in a sort of frozen, suspended-animation state. When the right conditions emerged — perhaps underground, where liquid water can occasionally flow — that life “wakes up” and begins performing its critical biological functions.

If this is the case, then there are still organisms to be found beneath the Martian surface, perhaps in the shallow sands just a few feet or even mere inches below our spacecraft. We’re likely only talking about single-celled life, perhaps not even reaching the complexity of a eukaryotic cell, but life on any world other than Earth would still be a revolution for science. NASA’s Perseverance rover, which launched successfully on July 30, 2020, will collect critical soil samples to attempt to test this hypothetical scenario, although no results on that front have yet been announced.

4.) Mars didn’t have life until Earth seeded it, naturally. 65 million years ago, a very large, fast-moving body impacted Earth, creating Chixulub crater and kicking up enough material to blanket the Earth in a cloud of debris, leading to the fifth great mass extinction in Earth’s history. And, like many massive impacts, this one likely kicked up small pieces of Earth all the way into space, the same way that impactors on the Moon or Mars send meteors throughout the Solar System, where some of them eventually land on Earth.

Well, a few impacts likely go the other way as well: sending Earth-borne material to other worlds, including Mars. It seems unreasonable that the material in Earth’s crust, rich in organic life, wouldn’t make it to Mars at all. Instead, it’s eminently plausible that Earth-based organisms made it to Mars and began reproducing there, whether they thrived or not. Perhaps someday, we’ll be able to know the full history of life on Mars, and determine whether any of it has the same common ancestor that all extant Earth life is descended from. It’s a fascinating possibility that isn’t easy to dismiss.

5.) Our modern space program spread Earth-based life to Mars. And, finally, perhaps Mars truly was a barren, lifeless planet — at least for billions of years — until the dawn of the space age. Perhaps spaceborne materials that weren’t 100% decontaminated or sterilized landed on the Martian surface, bringing modern Earth organisms with them as stowaways.

It’s the ultimate nightmare of astrobiologists: that there’s a fascinating history of life to uncover on another world, but we’ll contaminate it with our own organisms before we ever learn the true history of life on that world. More recently, the Tesla Roadster that was launched in 2018 was also not properly decontaminated, and could pose a risk of biological contamination of a foreign world.

In the worst case scenario, it could be the case that was surviving simple life on Mars of Martian origin, but that Earth life arrived and out-competed it, driving it to a rapid extinction. This very real, healthy fear is why we’re frequently so conservative, from a biological perspective, when we explore other planets and foreign worlds.

There is a tremendous hope that current and future generations of Mars rovers and orbiters will help us finally puzzle out whether Mars — either now or at any point in its past — has ever harbored life. If the answer to that question is affirmative, then it leads to an important follow-up question: is that life related to or independent of life on Earth? It is possible that life originated on Earth and seeded Mars with life; it’s possible that life originated on Mars and then seeded Earth; it’s even possible that life predated both Earth and Mars, and early forms of it took hold on both planets.

But at this point in time, we have no overwhelming evidence that life ever existed on Mars at all. We have a few hints that could be indicators of past or present life there, but entirely inorganic processes could explain each and every one of those observed results.

As always, the only way we’ll find out the truth is by conducting more and better science with superior instruments and techniques. As NASA’s Perseverance rover moves ahead to collect a variety of soil samples, the next step will be returning them to Earth for laboratory analysis. If we succeed at that, we could know for certain, within the next decade, which of these five possibilities is most consistent with the truth about Mars.