No, Earth is not overdue for a massive asteroid strike

That’s not how probability works. Or asteroids, for that matter.

“Bringing an asteroid back to Earth? What’s that have to do with space exploration? If we were moving outward from there, and an asteroid is a good stopping point, then fine. But now it’s turned into a whole planetary defense exercise at the cost of our outward exploration.” –Buzz Aldrin

It’s only a matter of time before a massive asteroid strike occurs on our world. There’s no doubt about it, as the Solar System and beyond is filled with massive rocks that travel, under the influence of gravity, through the interplanetary and interstellar medium. Every year carries with it a rough probability of such an impact for bodies of all sizes, from the pebbles that will never make it to the ground (a virtual certainty) to a 5–10 kilometer behemoth like the one that wiped out the dinosaurs (less than 0.000001% odds). But there’s a myth going around — propagated by scientists* at reputable agencies like Los Alamos National Laboratory, the American Geophysical Union and NASA’s Planetary Defense Coordination Office — that we’re overdue for one, and so one is likelier-than-normal in our future. The scientific truth indicates otherwise.

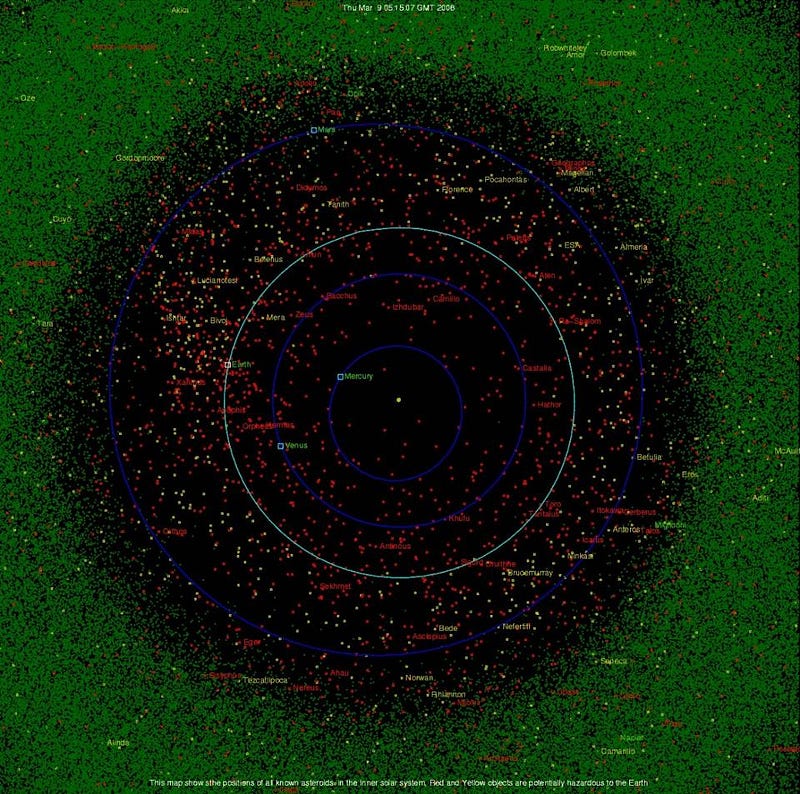

The asteroid population in our Solar System is the number one source of potentially hazardous impacts for our world. Almost all of the Earth-orbit-crossing objects we know of originate from the asteroid belt; of the impacts we find on our world and the other terrestrial planets (Mercury, Venus, Mars and even the Moon), the vast majority indicate an ultimate origin from our asteroid belt as well.

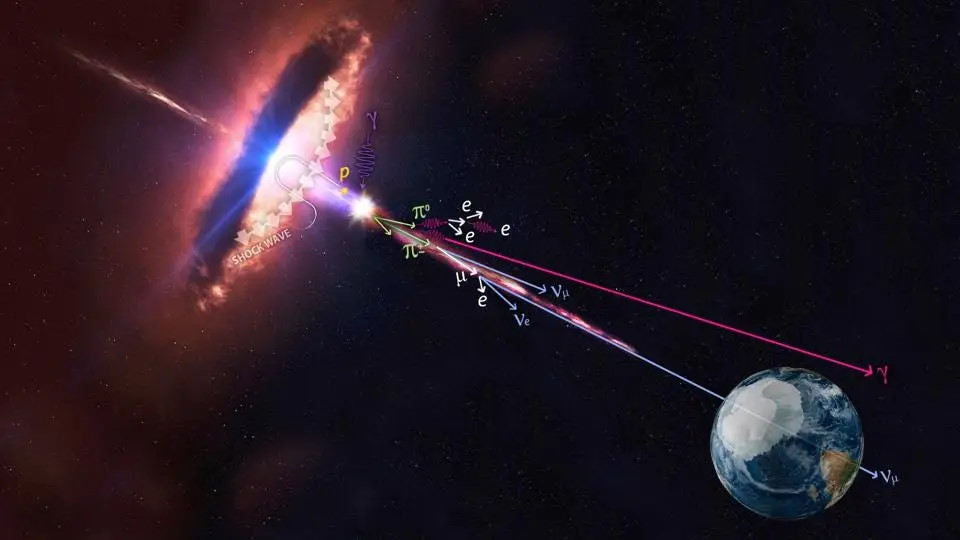

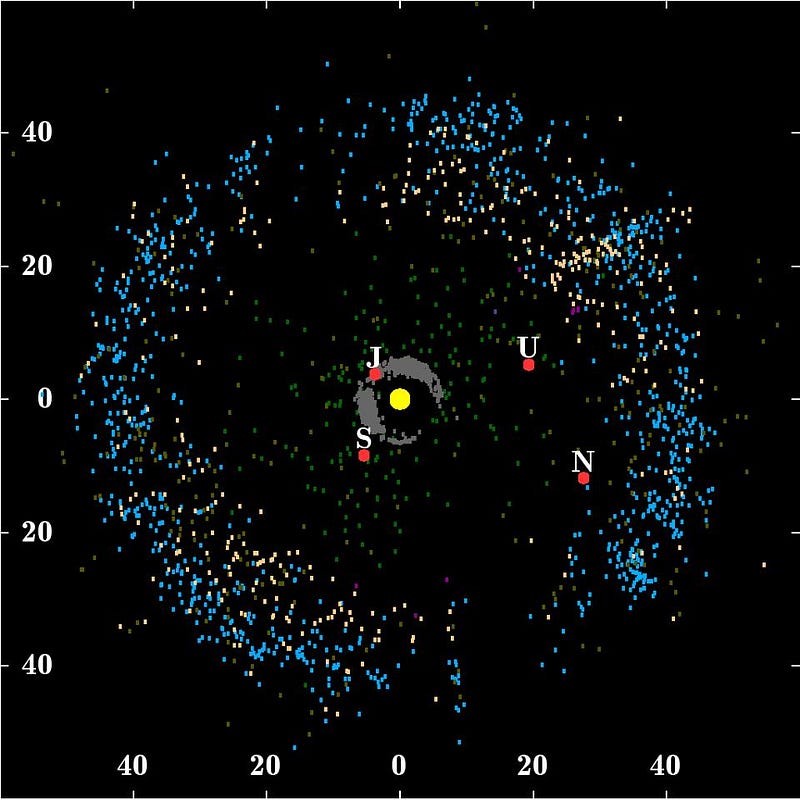

Based on what we’ve found in our Solar System, there are approximately a few million potential “10”s on the Torino scale, over 50 million potential “9”s and nearly a billion estimated potential “8”s. With lower likelihoods, Earth is also at risk from impacts due to centaurs, Kuiper belt objects, the Oort cloud and passing objects from the interstellar medium. But when rare events occur, they seem to inspire the worst fears in us.

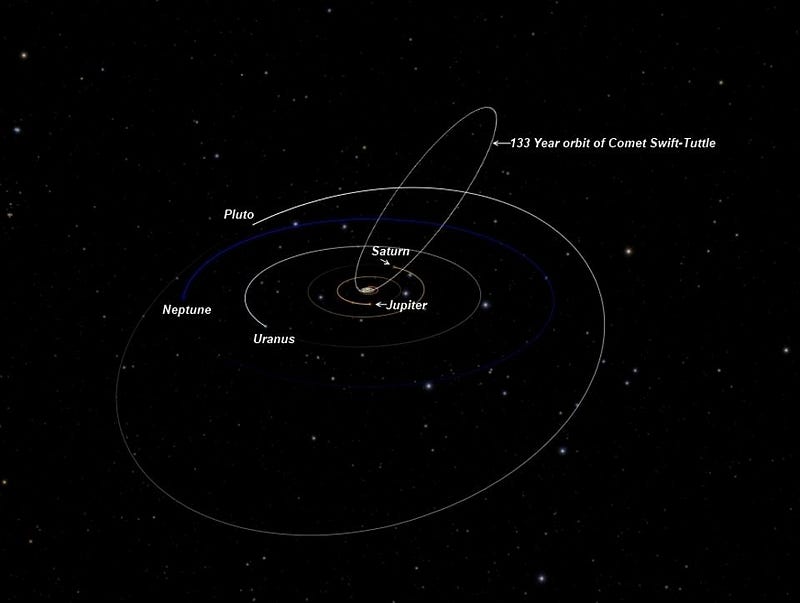

2013 was a banner year for collision terror. The year started off with the Chelyabinsk meteor, which caused millions of dollars of property damage and injured more than a thousand people. Then, a fast-moving Oort cloud comet — Comet C/2013 A1 (Siding Spring) — was discovered on a near-collision course with Mars. It was approximately half a kilometer across and wound up missing Mars by only 140,000 kilometers, or roughly 11 Earth diameters. If that object had struck Earth, it would have been a Torino-scale “9” disaster.

But a near-miss is still a miss. In fact, the largest impact in all of human history — both recorded and archaeologically discovered after-the-fact — is Barringer (meteor) crater in Arizona, which itself only rated an “8” on the Torino scale: the same rating as the 1908 Tunguska event. These events occur every few hundred years at most, and we can often go thousands or perhaps even ten thousand years between them. The Chelyabinsk event’s damage came mostly from broken glass; no meteors of the past century have had enough energy to rate above a “0” on the Torino scale.

Moreover, the Solar System itself is more cleared of potential impactors than at any time in history. They still occur, of course, but with lower frequency than ever before. Getting hit by a giant, fast-moving massive space rock is still a real threat, but there are only two common classes of impact. The most common type of impacts — from asteroids — are the most easily trackable. If we do a dedicated ongoing sky survey of the asteroid belt and all near-Earth asteroids, we could give ourselves decades or even centuries of lead time when it comes to these potentially hazardous objects.

The less common type — from long-period objects — are likely to give us less than two years of lead time, and potentially only months. If a fast-moving, massive body from beyond Jupiter, Neptune or even farther out plummets in towards the Sun, and happens to be on a collision course with Earth, our best option is to get to it as fast as possible with a nuclear impactor to try and divert it or break it up as much as possible. It’s the worst-case scenario, but thankfully, it’s a very unlikely one.

Trans-Neptunian objects are most likely to head towards Earth after a recent encounter with a nearby, passing star. But we haven’t had one in many hundreds of thousands of years, and there isn’t one slated for perhaps millions more. The odds of a city-killer asteroid striking Earth are below 0.1% every year, and most of the ones that will hit us will land in the ocean (70%) or over a relatively unpopulated area (25%). Only around 5% of the Earth’s surface has a sizable human population density inhabiting it, and the fallout from those events are minor even a small distance away from the direct impact. The extinction-level events are so low-risk that the most dangerous object known to humanity doesn’t pose any danger at all for more than the next 2400 years.

The odds of a massive asteroid strike are lower than they’ve ever been at any point in Earth’s history. Small asteroids will still hit us and we should still invest in the study and exploration of our Solar System and beyond, but we shouldn’t be afraid. The “quietness” of the past few millennia doesn’t mean we’re overdue for a city-killer asteroid; if anything, it means we’re living in a period of relatively low risk. Don’t let the catastrophic consequences in the game of “what if” blind you to the realities that of all the natural and human-caused disasters facing Earth, asteroids aren’t the one that should be topping our priority lists.

This post first appeared at Forbes, and is brought to you ad-free by our Patreon supporters. Comment on our forum, & buy our first book: Beyond The Galaxy!