Little Worlds Have Bigger Features

Why Everest and the Grand Canyon are so small. Yes, SMALL!

“How well I have learned that there is no fence to sit on between heaven and hell. There is a deep, wide gulf, a chasm, and in that chasm is no place for any man.” –Johnny Cash

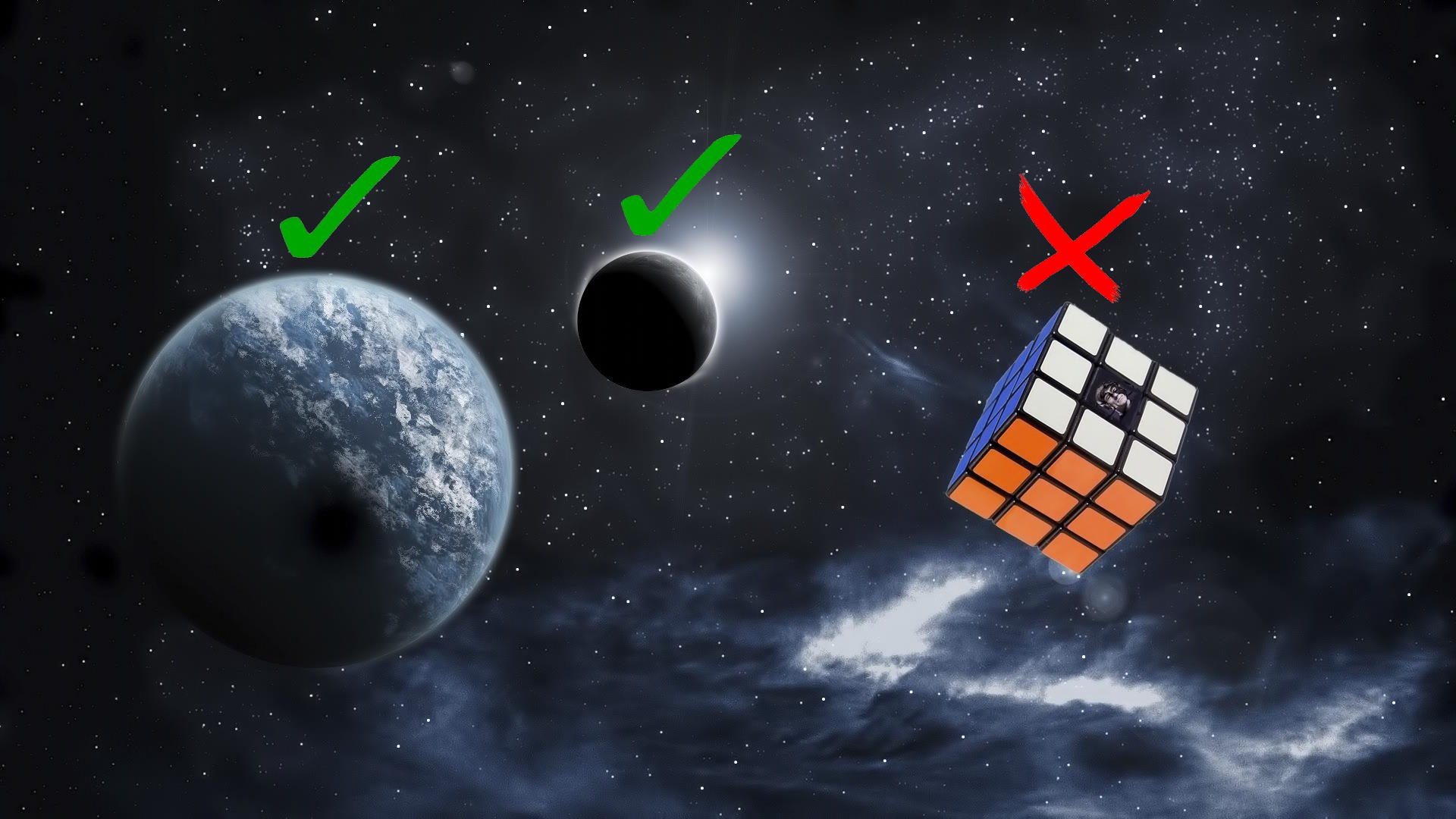

Here on planet Earth, the largest mountains seem absolutely incredible, stretching tens of thousands of feet from top to bottom. The grandest valleys are absolutely tremendous, spanning hundreds of miles in length, more than a dozen miles wide and over a mile deep. These fantastic features — Mount Everest, Mauna Kea, the Grand Canyon — are some of the greatest natural wonders our planet has to offer. As the largest rocky planet in our Solar System, you’d think Earth would be awfully tough to beat on these fronts. And yet, these massively imposing structures are downright paltry when it comes to what else goes on in our Solar System.

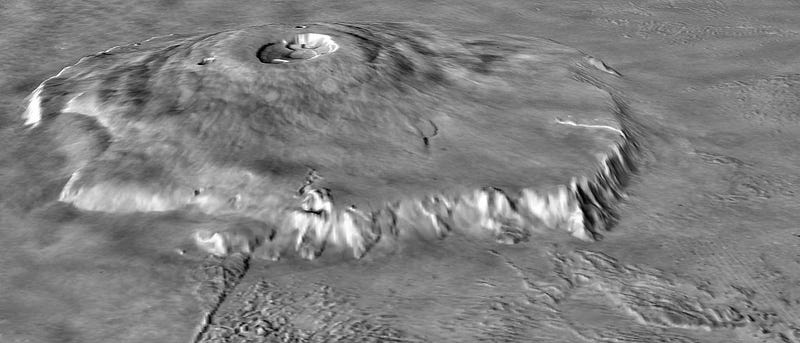

Earth’s tallest mountain, Mauna Kea, extends over 30,000 feet (about 6 miles, or nearly 10 km) from base-to-peak. Nearly a mile (1.5 km) larger than Everest by this metric, none of the other famed mountains on Earth compare. But our Solar System is full of worlds much smaller than Earth with much, much larger mountains or high-elevation features than our world has ever known. Our little sister world, Mars , at barely half the diameter of Earth, has a series of mountains that outstrip anything our world possesses. It’s fantastic mountains include Pavonis Mons (6.8 miles/11 km), Elysium Mons (7.8 miles/13.9 km), Ascraeus Mons (9.3 miles/15 km) and the grandest one of all, Olympus Mons, which is more than twice the size of Mauna Kea from base-to-peak, at a tremendous 13.7 miles (around 22 km).

It isn’t just Mars that dwarfs Earth, either. Many of the well-studied moons in our Solar System have features far grander than our planet, and likely other worlds that we haven’t studied as well can defeat Earth as well. Some of the worlds that have taller mountains that we do include:

- Jupiter’s moon Io, slightly smaller than our own Moon, has a number of enormous mountains on its volcanically active surface, with Boösaule Montes as the largest, which measures 10.6 miles (17 km) from base-to-peak.

- Saturn’s moon Iapetus, just half the size of Io, has an equatorial ridge that rises up 12.6 miles (20 km) from base-to-peak, encircling the entire world. It’s origin is still a mystery.

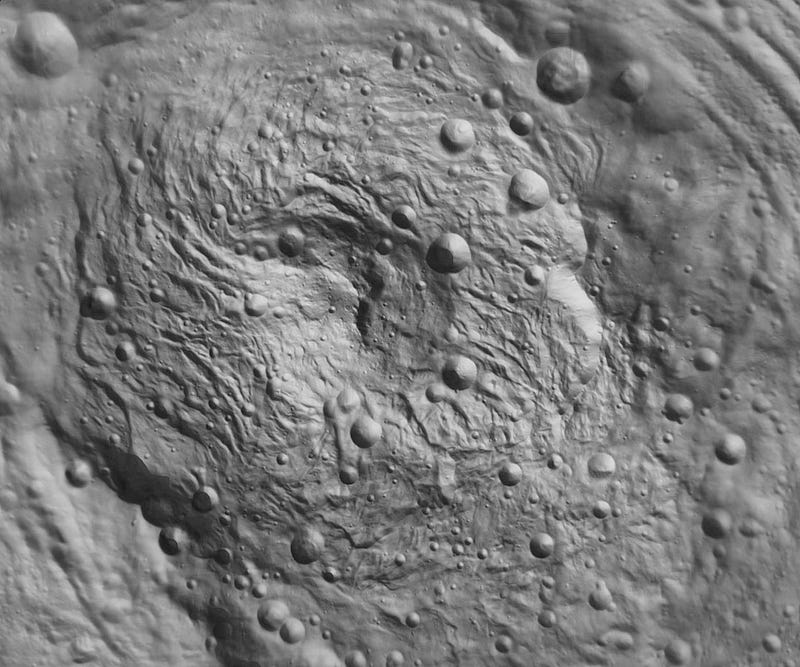

- And most impressively, the second largest asteroid, Vesta, with a diameter of only 326 miles (525 km), has the Solar System’s largest mountain of all: Rheasilvia Mons, with an incredible base-to-peak height of 14.2 miles (23 km), having arisen from an impact that made a crater more than 90% of Vesta’s diameter.

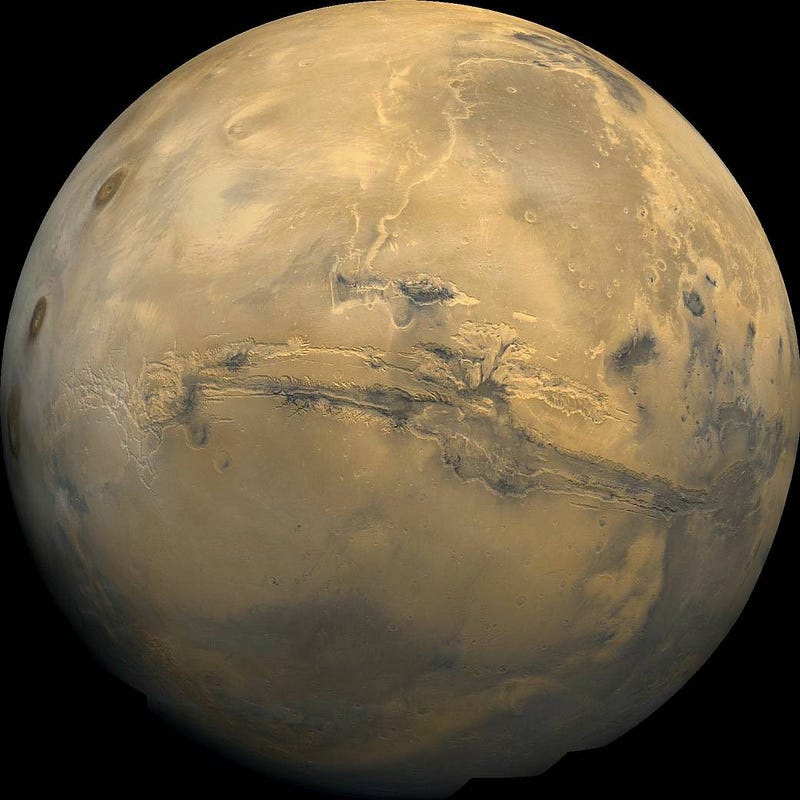

The same pattern applies to the grandest canyons as well. Sure, the grand canyon is legitimately big, carved by thawing ice ages repeatedly flowing in massive deluges down the same path over hundreds of millions of years. But other worlds have other means of carving massive paths: glaciers, other surface liquids, or geologic cracking and cooling.

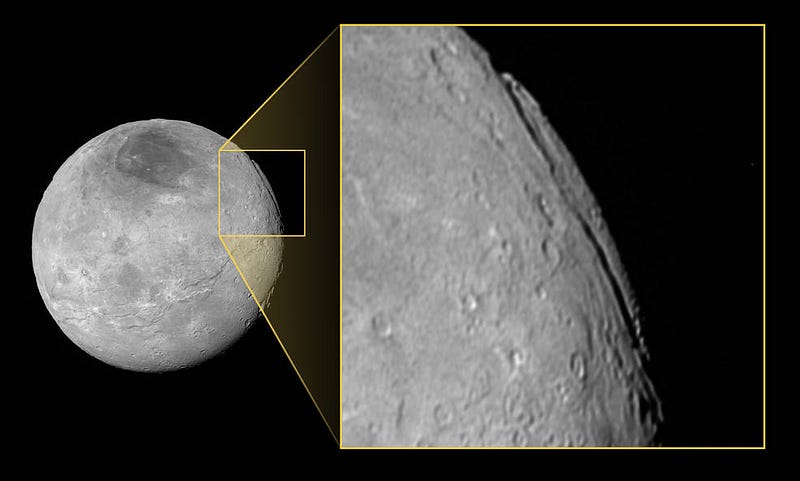

Valles Marineris on Mars is over 2500 miles long, 120 miles wide and 4 miles deep, dwarfing Earth’s grand canyon. Even the rift valleys in the mid-ocean on Earth may not stand up to this magnificent martian feature. In addition, Mercury’s enormous scarps leave cliffs that are 600 miles long and more than 1.8 miles high. In the outer Solar System, Uranus’ moon Miranda has a cliff-like feature — Verona Rupes — that’s an incredible 12 miles (20 kilometers) deep, the largest known in the Solar System. And New Horizons recently discovered a comparably massive chasm on Pluto’s moon Charon: Argo Chasma, at an estimated 430 miles in length and around 5.5 miles (9 km) deep, with spots potentially rivaling Verona Rupes for the largest cliff face in the Solar System.

So why does Earth, the Solar System’s largest rocky world, not have the largest mountains and chasms in the Solar System? And why is it surpassed by worlds so much smaller? That, itself, is the answer: smaller worlds have less gravity, less sphericity, less uniformity, and less resistance to having their shape deformed by outside forces. Whether geologic activity, cooling-and-contraction, volcanism, or impacts from bombardment, the same forces that form these features on Earth are more effective on smaller, less massive worlds. Without large amounts of gravity to regulate and dampen these features, they can grow to enormous proportions, encircling an entire world or — as may be the case in Saturn’s rings — destroying it entirely.

Little worlds have bigger features, and so the “tallest mountain” or “grandest canyon” on Earth just can’t compete with the rest of the Solar System. Who knows? Perhaps an unexplored, small world that’s still out there will shatter these records entirely, and that the Solar System’s record book still has many more pages that need to be written?

This post first appeared at Forbes, and is brought to you ad-free by our Patreon supporters. Comment on our forum, & buy our first book: Beyond The Galaxy!