Are All Great Leaders Bound Forever to Their Convictions?

The “trouble” with “the modern world,” British philosopher Bertrand Russell wrote, is that “the stupid are cocksure while the intelligent are full of doubt.” It’s easy enough to think of examples that lend support to both claims. Less-than-brilliant people do often cling to bad ideas (though ideological purity is hardly their exclusive preserve), and smart people do sometimes overthink things so much that they work themselves into a frenzy of wishy-washy uncertainty.

It’s curious that in politics, being cocksure is exactly what nearly all candidates seek to broadcast. No candidate wants to appear undecided. And everybody resists charges of flip-flopping, no matter how incontrovertible the evidence. In the seventh GOP presidential debate on January 28th, Fox News moderators pulled Video Daily Double-style tricks on Marco Rubio and Ted Cruz, contrasting footage of their prior statements with their current policy positions. Neither candidate took this as an opportunity to say: “Well, I’ve changed my mind.” Instead, both undertook logical and linguistic contortions to try to explain away what was an obvious change of heart — or an opportunistic shift based on political expediency.

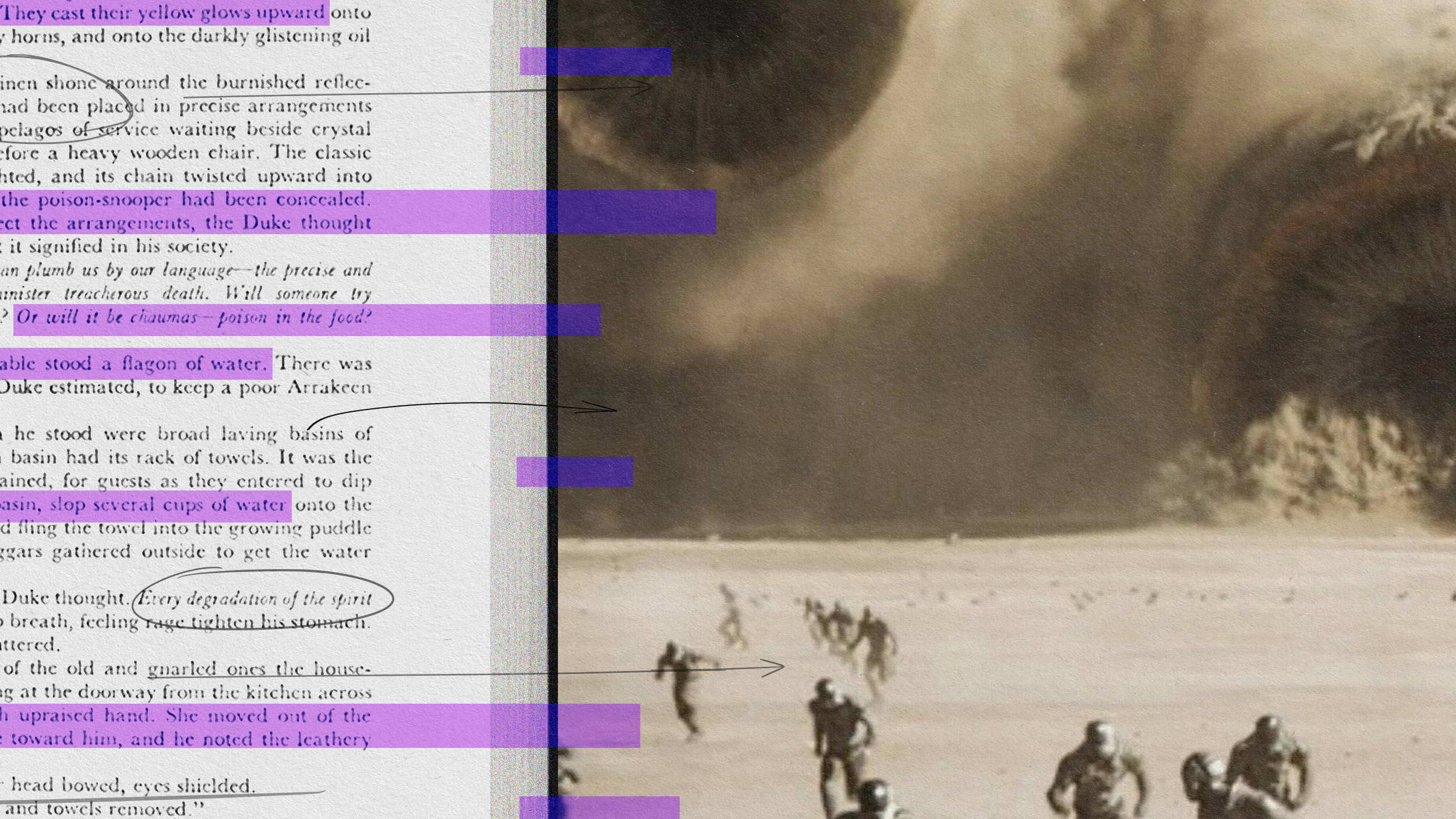

But changing one’s mind is no vice. In fact, as Al Pittampalli argues in his new book, Persuadable: How Great Leaders Change Their Minds to Change the World, being stuck in one’s views is a recipe for torpor and failure. You’ve got to keep your mind open if you want to succeed. The cultural bias toward resolute and unshifting views “presents a huge problem for society,” Pittampalli argues. “In a working marketplace of ideas, good ideas find plenty of buyers and become more prevalent. Bad ideas find fewer buyers and become more obscure. But markets require both sellers and buyers. In our broken marketplace, in business, politics, and relationships, everyone wants to sell an idea. Far too few people are prepared to buy someone else’s.” The values of “confidence, conviction, and consistency” are overrated. The best leaders “constantly question their own beliefs, welcome dissenting points of view, and are fully prepared to change their minds in the face of new evidence.” Mind changers “don’t particularly care if that makes them look less heroic.” In the long run, they’ll be more likely to emerge as heroes.

Pittampalli cites a number of business and political leaders whose open-mindedness has served them, and the rest of us, well. Examples include Abraham Lincoln, who steered the United States through a crisis that could have left it ripped in two for good; Alan Mulally, who saved Ford Motor Company from near death in the late 2000s and returned it to profitability without taking government bailout funds; and Billy Graham, the televangelist and adviser to presidents who has saved, by his lights, over 3 million souls.

And Pittampalli counts Jeff Bezos, CEO of Amazon, as a leader nimble enough to be persuaded to change course in the face of a changing business climate:

“When Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos saw that e-readers might threaten his flourishing physical book business, he wasn’t just open to change — he leaned into it. Despite the fact that e-books would undermine his core business, he tapped one of his most trusted associates to focus on digital publishing. ‘I want you to proceed as if your job is to put everyone selling books out of a job,’ he told him. Years later, Amazon dominates the e-book market.”

What all these leaders have in common, Pittampalli observes, are three things. First, open-mindedness. They “are willing to change their opinions as circumstances change” and thus “see the world more clearly.” Whereas most of us try to resist reorienting our cluster of beliefs and dig in our heels, effective leaders “who are skeptical of their own beliefs and are willing to change their mind when they encounter new evidence make more accurate predictions.”

The second quality is speed. These individuals (and women do belong on the list, including Sheryl Sandberg, though Pittampalli unbelievably mentions nary a one in the essay promoting his book) are “able to more quickly abandon old beliefs in favor of a new one” because they “treat their beliefs as temporary.” It doesn’t take years to shift a view to which you have little emotional attachment; it takes a momentary insight. That agility helps persuadables “beat out their competitors.”

Third, pathbreaking leaders do not have fragile egos. They “are able to address their weaknesses” and recognize their own flaws. They are unruffled when other people tell them uncomfortable truths about their ideas.

It’s easy to take this suggestion too far. The idea is not to adopt a position of radical uncertainty, which easily devolves further to nihilism. The thought is not that no position is better than any other, so why bother. The insight, instead, as philosopher John Stuart Mill wrote in his seminal work On Liberty, is people must resist the tendency to let their beliefs encrust around them:

“However unwillingly a person who has a strong opinion may admit the possibility that his opinion may be false, he ought to be moved by the consideration that however true it may be, if it is not fully, frequently, and fearlessly discussed, it will be held as a dead dogma, not a living truth.”

Pittampalli’s focus is on leaders, but his advice applies well to anybody and everybody. Whether you’re at the helm of a Fortune 500 company or of the world’s last superpower, running a small business or just managing a family, it’s crucial to have convictions and to be decisive. But it’s equally important to keep in mind that your convictions (even your strongest and longest-lasting) may at times need to be revised — or replaced.

—

Steven V. Mazie is Professor of Political Studies at Bard High School Early College-Manhattan and Supreme Court correspondent for The Economist. He holds an A.B. in Government from Harvard College and a Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of Michigan. He is author, most recently, of American Justice 2015: The Dramatic Tenth Term of the Roberts Court.

Image credit: shutterstock.com

Follow Steven Mazie on Twitter: @stevenmazie