Why are intelligent people more likely to abuse drugs?

Photo credit: Itay Kabalo on Unsplash

- Numerous studies have confirmed the link between intelligence and substance abuse.

- However, the mechanism for this correlation has been difficult to pin down.

- Why would more intelligent people, who should ostensibly know better, practice such a risky habit?

No mathematician has ever published more papers than Paul Erdős. The 20th-century mathematician was brilliant, eccentric, and prolific, publishing a record 1,525 papers. By the age of four, Erdos could calculate the number of seconds someone had lived if they gave him their age. He contributed to a wide variety of mathematical disciplines, including discrete mathematics, probability theory, Ramsey theory, graph theory, and others.

He worked 19-hour days. And, among other things, he loved amphetamines.

When Ronald Graham, a concerned friend and fellow mathematician, bet him $500 that he couldn’t stay off his drug of choice for a month, Erdős accepted and easily won the challenge. When the 30 days was up, Erdős said to Graham, “You’ve showed me I’m not an addict. But I didn’t get any work done. I’d get up in the morning and stare at a blank piece of paper. I’d have no ideas, just like an ordinary person. You’ve set mathematics back a month.” Erdos resumed taking amphetamines and did so for every day of his life until his death 17 years later.

Numerous studies have documented the relationship between intelligence and substance abuse. This relationship should be a negative one. After all, recreational drugs can damage your health, addiction costs huge amounts of money, and the legal consequences can be dire. But in fact, intelligence and substance abuse have a positive relationship: intelligent individuals are more likely to abuse drugs than less intelligent individuals.

Unsplash

Evidence for a link between intelligence and substance abuse

A 2011 study conducted on nearly 8,000 people measured their IQ scores at ages 5 and 10. Then, the study followed up with these individuals at ages 16 and 30. Individuals from this group with higher IQ scores were more likely to use cannabis, cocaine, ecstasy, amphetamines, or a combination of these drugs. Women with IQ scores in the top third, for instance, were more than twice as likely to have used cannabis or cocaine by 30 than those in the bottom third. Men with high IQs were nearly twice as likely to have taken amphetamines and 65 percent more likely to have taken ecstasy compared with men who scored less.

The same relationship exists for alcohol consumption. Even accounting for religion, social class, parental education, and satisfaction with life, intelligence has been found to be the second-greatest predictor of alcohol consumption, the first being gender. Even boozier countries tend to have higher than average daily wine and beer consumption.

It’s clear that there is some kind of positive relationship between substance abuse and intelligence, but why does this relationship exist?

Photo credit: Dani Ramos on Unsplash

Possible explanations

There are several different theories.

First, it could be a side effect of the conditions that give rise to a high IQ. You’re more likely to have a high IQ if you grow up in a socioeconomically advantageous environment — there’s less stress, better access to education, better healthcare, and other factors that facilitate the growth of intelligence. This kind of environment shields people from the downsides of drug use.

People growing up in socioeconomically disadvantaged environments, however, can’t afford drug treatment, highly capable lawyers, or the funding their habit requires without resorting to unsavory activities, so they’re exposed to the dangers of drug use far more frequently.

Despite this, an intelligent impoverished person might look at their (wealthy) peers, see that their real-life experience doesn’t back up the messaging of anti-drug campaigns taught in schools and, therefore, feel more comfortable taking recreational drugs. This theory is corroborated by the fact that — out of nearly all other drugs — individuals with higher IQs are less likely to smoke cigarettes. The downsides of cigarette smoking are so patently obvious that it’s more reasonable for an affluent (and influential) person to avoid it than, say, cannabis or ecstasy.

Another theory

Evolutionary psychologist Satoshi Kanazawa has a different theory: the Savanna-IQ Interaction hypothesis.

Life evolves to become better adapted to a certain environment. Giraffes, for instance, have long necks so they can see predators (and eat lofty fruit), dogs spin around in circles before they lie down to check their surroundings, and some birds migrate to avoid the winter. These adaptations are positively selected for because the creatures that possess them are more likely to survive and reproduce.

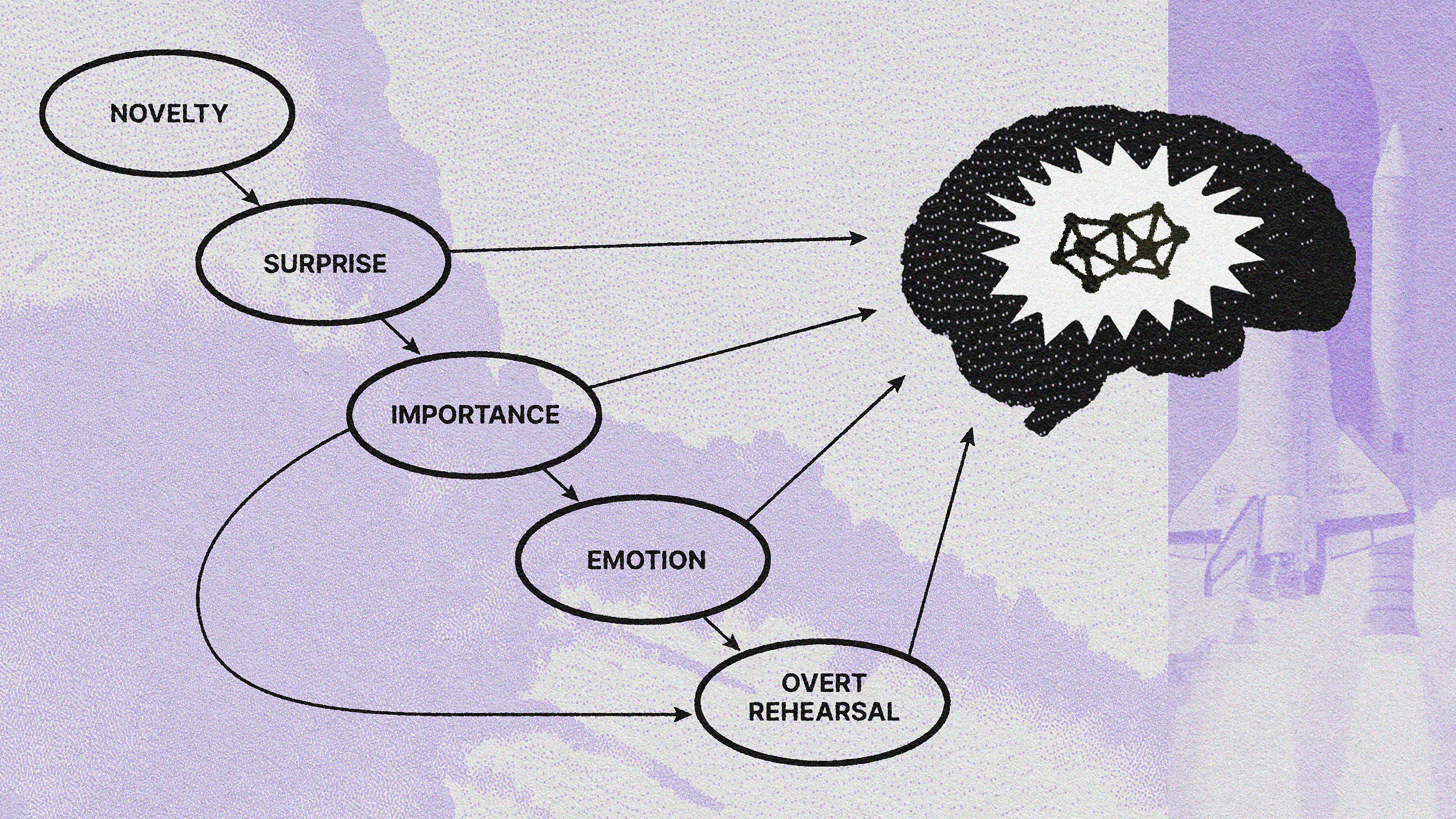

However, environments are dynamic; the entire spectrum of useful behaviors can’t be hard-wired into animals. The Savanna hypothesis contends that general intelligence — which IQ tests routinely measure — evolved as an adaptation to solve evolutionarily novel problems — that is, the unexpected challenges of the environment.

The Savanna hypothesis suggests that outside of the savanna — Homo sapiens’ “natural” environment — general intelligence would be selected for, since there are more evolutionarily novel experiences than evolutionarily familiar experiences, or situations in which we have a hard-wired response to. It would also stand to reason that humans who were both intelligent and inclined to try novel things would leave the savanna and become biologically successful across the globe.

So, the humans that left the savanna and succeeded outside of it would be both intelligent and inclined to try new things, such as drugs. This hypothesis proposes that this link between intelligence and novelty is why intelligent people do drugs. The fact that drugs are unhealthy would be less relevant than the fact that drugs are a more novel experience than, say, being charged by a predator, a scenario for which we have a hard-wired response to.

Criticisms of the Savanna-IQ Interaction hypothesis

Kanazawa hypothesis has been popular in the media, but it has also attracted some criticism from other scientists. (In addition, any article discussing Kanazawa would be remiss not to point out his more problematic positions, some of which he derives from the Savanna Principle; regardless, the science should be criticized on the basis of science rather than character). First, the association between intelligence and seeking novelty may be more easily explained: Other research has shown that variations in the dopaminergic system are associated with corresponding variations in novelty-seeking (or openness to experience) and intelligence.

Another criticism of the Savanna-IQ Interaction hypothesis is that intelligence likely evolved long before humans began traveling outside of the savanna and migrating across the globe. There’s also the fact that humans have been consuming drugs for thousands of years, suggesting that their use might not be so novel after all. There are numerous other points of contention against the hypothesis, but very few other proposals have been able to satisfactorily explain why intelligent people seek out novel experiences like substance abuse.

It may simply be that intelligent people are more easily bored and that drug use is the easiest way to alleviate boredom, or that intelligent people find more utility in their drug experiences and can incorporate lessons learned from altered states into their worldview. Ultimately, the research simply doesn’t have an iron-clad reason for why intelligence and substance abuse are related, we simply know that they are.

Even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had some understanding of this connection — Sherlock Holmes isn’t an opium addict for no reason.