Embracing the Senses: Balancing Novelty and Habituation

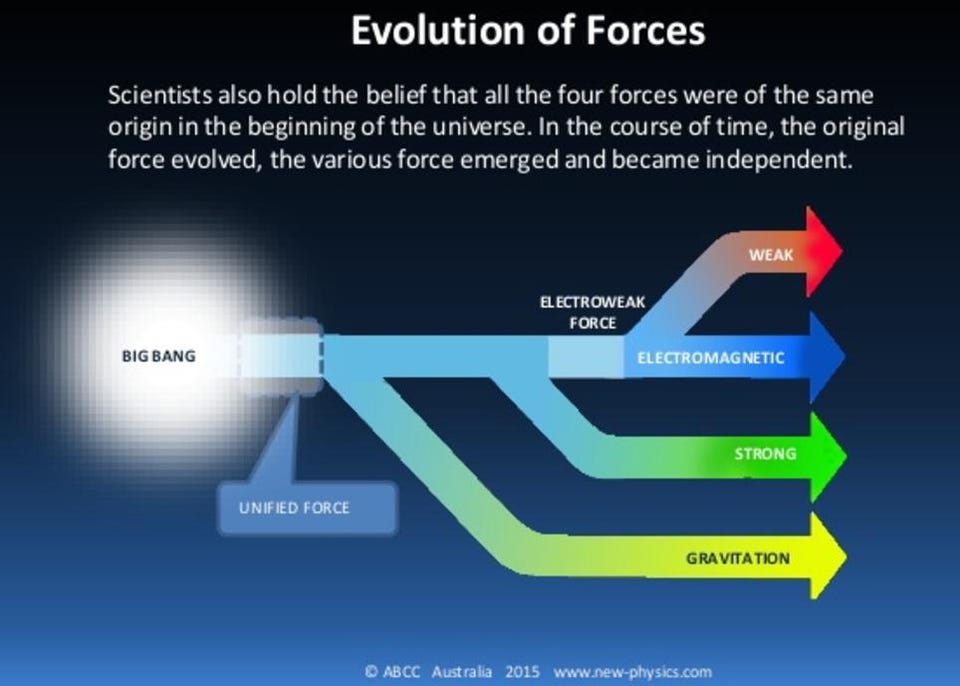

One paradox of creativity is that it’s restricted by the senses. The eyes and visual cortex perceive a narrow slice of the electromagnet spectrum. Our sense of taste and smell is minuscule compared to the rest of the animal kingdom. We’re deaf to most frequencies. If creativity sees no boundaries, then it’s blind to what evolution endowed in us.

Yet, artists throughout history spent careers trying to transcend the senses. Cage composed silent music, Robert Rauschenberg painted blank canvases and Marcel Duchamp signed a porcelain urinal and called it art. Implied was that with enough time and exposure anyone will come to enjoy even the most abstract and absurd art.

This assumption is not true. In 2002 Steven Pinker published The Blank Slate and corrected the widespread belief that human beings are born without innate traits and that culture and environment shape everything. In contrast, humans arrive into the world predisposed with traits immutable by external factors. This is true for aesthetics, where we demonstrate a variety of innate preferences.

One takeaway from Pinker’s reminder is that if you are interested in delivering pleasure to a wide-range of people don’t look to modernists and postmodernists for inspiration. For them, art was surveying the aesthetic landscape and rejecting commonly held preferences. People like books with plots? People like poetry that rhymes? People like music with harmony? Let’s do the opposite, they said.

It’s worth wondering what inspired these artists to adopt an avant-garde attitude. It certainly wasn’t mass-appeal. Perhaps it was snobbery. Art is about standing out from the crowd. In any given community where people create things some will always want to be different. They see the way forward as looking at what everyone else does – what’s easy and pleasurable – and rejecting it. Whenever there is an aesthetic consensus in a community, a select few will rebel against. (This is true even when it comes to defining art; whatever definition you come up with, a snob will come up with another one or argue that art can’t be defined.)

I don’t think this was the case for Cage et al. In The Clockwork Muse the late Professor of Psychology Colin Martindale says that habituation is “the single force that has pushed art always in a consistent direction ever since the first work of art was made.” The job of the artist is to counter habituation with novelty. Art changes because it is govern by habituating audiences and novelty-creating artists. Both are always reacting to each other.

The need for novelty is built into the definition of being an artist, Martindale says, but the amount varies. Mainstream artists only require small doses of novelty while the Cage’s of the world demand extreme amounts. Creators of high art aren’t snobs trying to stand out from the crowd, they’re just easily bored.

Critically acclaimed art finds a middle ground. It’s usually unfamiliar and misunderstood at first. But with more exposure the audience comes to appreciate previously overlooked details. As I stated earlier in a slightly different context, this is why in terms of enjoyment classic pieces of art are not fleeting: innovative features and novelty give us something different with each exposure. We don’t get sick of them because there is something new each time around. It takes many repeats for overabundance to downgrade its value.

Creators of classic works of art succeed because they understand the relationship between novelty and habituation. They know that they will always need to counter an inherently habituating audience with art that is complex and that incorporates something new. Good art finds this middle ground. It doesn’t try to transcend the senses; it embraces them.