We Need a United Nations of World Religions

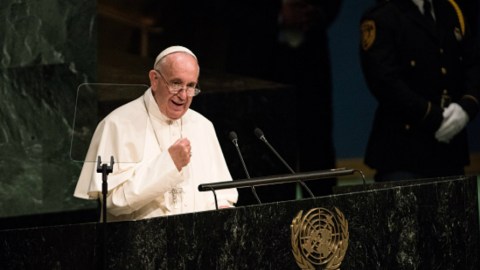

During Pope Francis’ 2015 North American Pope-a-palooza tour he gave a speech in front of the United Nations general assembly. Francis pleaded to the room of diplomats in favor of stronger international commitments to peace, environmental stewardship, and social/economic justice.

Basically he asked the assembly to more or less do its job.

The United Nations gets a bad rap for being both dysfunctional and politically impotent — both fairly legitimate gripes. Yet despite its many faults, the organization has contributed to an unprecedented geopolitical state of relative peace and prosperity. In short: Globalization made it so the social and economic fates of the world’s major powers were tied together. The U.N. and similar international organizations have played a key role in maintaining that status quo. They’re like duct tape holding things together; it’s not perfect and it’s not pretty, but it’ll do.

“In [Shimon] Peres’ eyes, Pope Francis would head up this ‘UN for religions’ because he is universally respected and could spearhead efforts to broker peace in the Middle East.”

If such an alliance can be used to unite independent states, could a similar model work for world religions? This was an idea proposed last year by former Israeli president Shimon Peres. He suggested that an organization called “the United Religions” could bring together leaders from various worldwide religions with the goal of promoting interfaith peace and understanding. In Peres’ eyes, Pope Francis himself would head up this “UN for religions” because he is universally respected and could spearhead efforts to broker peace in the Middle East. Peres even pitched the idea to the pontiff when the two men met last September.

Anders Fogh Rasmussen, former prime minister of Denmark and former secretary general of NATO, discusses how climate change is expected to shift geopolitical priorities — particularly in the arctic region.

Would the United Religions work? It’s difficult to say, mostly because faiths — unlike nation-states — tend to be rather amorphous. For instance, not every major organized religion features a leader equivalent to the pope. Islam and protestant Christianity, for example, are so fractured and rife with variant sects that it’d be difficult to assess who could possibly represent major swaths of the religious population. To host a representative from every denomination of every major religion would beget a stadium’s worth of clerics — and that’s before having to ask whether atheists and non-believers would be invited as well.

Then there’s the issue that some religions consider themselves the one true faith. To join a United Religions organization in which — ostensibly — each religion exists on equal ground would be akin to blasphemy. The U.N. is full of nations that don’t particularly like each other, but at least it’s for the most part a matter of political machinations rather than innate spiritual disdain.

“In the past, most of the wars in the world were motivated by the idea of nationhood. But today, wars are incited using religion as an excuse.”

For the sake of this thought experiment, though, let’s pretend that someone pulls this off and the United Religions is established as a sort of Justice League for religious leaders. Could they really effect positive change? Peres thinks so because the world has so drastically evolved over the past half-century. “In the past,” he explained, “most of the wars in the world were motivated by the idea of nationhood. But today, wars are incited using religion as an excuse.”

Peres believes that just as the U.N. helped pacify nations, a U.R. could help pacify religions. Ignoring several of the holes in his argument (religious warfare flourished well before nationhood was even a concept), it’s not hard to at least imagine a situation in which the hypothetical U.R. finds common ground in humanism and charity. Beyond that, it feels like a stretch to assume a group of old, zealous men could achieve anything near worldwide religious harmony.

“… a U.N. for religions could be a sort of beacon for future aspirations.”

And that somewhat cynical take may very well have been how Francis reacted to Peres’ pitch. By all reports, the pope was very understanding and polite when hearing Peres out, yet would not commit to the idea. I imagine he placed the idea in his back pocket along with his Starbucks receipts to be tossed out at the end of the day.

Yet despite the long odds, a hypothetical U.N. for religions could be a sort of beacon for the future aspirations. The current state of worldwide faith, rife with ignorance and distrust, makes it seem unfeasible. But who’s to say that’s what religion will look like in 50 years? Or 100? If anything, the existence of a U.R. would indicate that we’ve made great progress in global understanding. That’s the kind of world I’d want to live in, even if it’s not a world likely to exist.

It wouldn’t be perfect and it wouldn’t be pretty, but it would do.

—

Robert Montenegro is a writer, playwright, and dramaturg who lives in Washington DC. His beats include the following: tech, history, sports, geography, culture, and whatever Elon Musk has said on Twitter over the past couple days. He is a graduate of Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. You can follow him on Twitter at @Monteneggroll and visit his po’dunk website at robertmontenegro.com.

Read more at DC Clothesline

(Photo by Andrew Renneisen/Getty Images)