Some earthquakes last for seconds, others for minutes — and a few for decades

- Stronger earthquakes tend to last longer. This is because it takes a while for the earthquake to travel down a fault.

- A slow slip event, similar to an earthquake, can last months or even years.

- A massive earthquake may have been triggered when the asteroid that killed the dinosaurs hit the Earth, making life even worse for our soon-to-be-extinct predecessors.

Earthquakes are terrifying, even if they are usually brief. Within a few seconds they can wreak widespread destruction, causing great structural damage, shifting landmasses, and triggering tsunamis.

Not all earthquakes are so short-lived, either. Earthquakes can last for minutes and even longer. Some slow-slip events, which may be related to earthquakes, can even last decades. What causes an earthquake to last so long?

The strongest earthquakes

In 2004, a 9.1 to 9.3 magnitude earthquake rocked the Indonesian island of Sumatra. Releasing as much energy as a 100-gigaton bomb, the quake was felt around the world. A quarter of a million people perished or went missing in the tsunami that followed. Not only was it one of the strongest earthquakes recorded since the invention of the seismograph, but it was also one of the longest, at 10 minutes of shaking.

The 1960 Valdivia earthquake in Chile was the strongest ever recorded, with a magnitude from 9.4 to 9.6. The fault that ruptured was anywhere from 500 to 1,000 km long, and the resulting earthquake left about 2 million people homeless.

Both of these were what is called megathrust earthquakes, and they happen when one tectonic plate slips under another. As one plate sinks, sometimes it gets stuck. Tension builds as the plates accumulate energy. Eventually, this tension is released. The subducting plate jolts forward as the upper plate is forced upward in a powerful megathrust. These are the world’s most powerful earthquakes, and unfortunately, they are often some of the longest as well.

Cracks growing over time

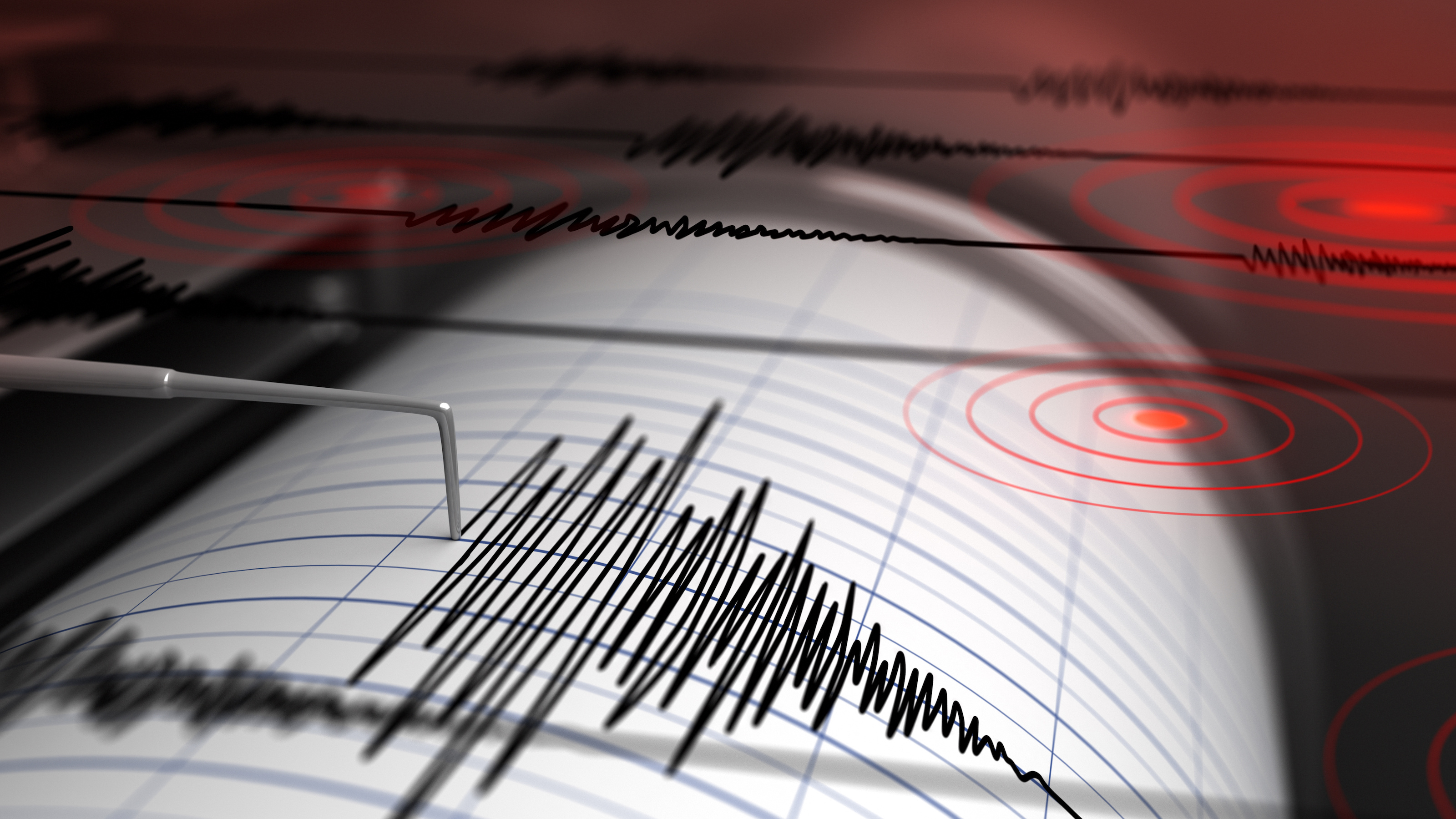

Duration is not always the best metric to describe an earthquake. That is because the timing is not always easy to pinpoint. You can define the duration of an earthquake by how long shaking is felt on the ground, but you can also define it by the length of the wavetrain on a seismograph.

In general, the stronger the earthquake, the longer it is. That is because “the rupture speed (how quickly the front of the rupture moves along the fault) does not vary too much, but the size of the fault that breaks during the earthquake does increase with magnitude,” William Frank, a professor specializing in earthquakes and tectonics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, explained to Big Think. “The rupture speed of the slip front… stays more or less the same because it depends on the material properties of the rock that hosts the fault. And because most continental rocks are pretty similar, we often see a rupture speed of around 2 km per second.”

As a general rule, the size and duration of an earthquake depend on the length of the fault that slips. When an earthquake begins, we do not necessarily know how big it will be or how long it will last, because the slippage still has to propagate down the fault.

“You [can] think about an earthquake like a crack that grows over time,” explains Joan Gomberg, a geophysicist at the U.S. Geological Survey. “Like on your windshield, you get a little crack and then it grows, it grows, it grows. Well, an earthquake essentially does the same thing,”

What about aftershocks? These happen when a fault ruptures and redistributes stress in the region. The new stresses can then release, and this causes the aftershocks.

Slipping for decades

Recall that we mentioned slow-slip events. While not technically an earthquake, such an event releases energy built up in a fault over the course of hours, months, or years.

A slow-slip event is similar to an earthquake in that both release energy pent up between tectonic plates. But slow-slip events happen gradually — so gradually, in fact, that they are very hard to detect. They are not felt by quaking at the surface.

The so-called “world’s longest known earthquake” in Sumatra was not really an earthquake at all, but one of these slow-slip events. This event lasted for 32 years but was undetected by the people who lived through it. It ended with an 8.5 magnitude earthquake in 1861.

These events are different from normal earthquakes. “The slow ‘earthquakes’ are the benign kind because they happen very slowly and they don’t send out… waves,” explains Gomberg. “It’s the waves that make the ground shake, and that’s what makes them dangerous.”

Eric Lindsey of the University of New Mexico and his colleagues have studied the Sumatra slow-slip event. Since the event was not felt by any person or recorded by any seismograph, they had to reference an unlikely source for records of what happened — coral.

“In tropical areas like Sumatra, certain corals grow in small circular colonies known as ‘microatolls’ that grow up to a certain elevation just below sea level, then grow outward at that constant elevation,” Lindsey explained to Big Think. “If sea level rises, the corals will grow upward to the new level, or if it drops, they will die off everywhere above the new level.”

Lindsey and his colleagues carefully studied corals in this area and created a history of the sea level. What they found was surprising — the sea level changed rapidly, moving either up or down over the course of three decades. What they were seeing was evidence of the crust of the Earth shifting during a slow-slip event.

It is quite possible that other events like this happened in other areas around the world, but it is hard to know for sure. “Coral microatolls are not found in most subduction zones, so it’s difficult to obtain a similarly long and precise record of relative sea level in other areas,” Lindsey explains. This may change in the future, however, with various means for geodetic observation that can carefully monitor how the Earth changes over time.

Adding insult to great injury

There is another, final cause for an earthquake — an asteroid impact.

Sixty-five million years ago, an asteroid 10 km wide hit the Earth, ending life for the dinosaurs and many other species of life on the planet. This asteroid may have created an earthquake that lasted for weeks or even months. This earthquake would have released 50,000 times more energy than the 2004 earthquake in Sumatra.

Evidence of this earthquake was found by Ph.D. student Hermann Bermúdez. While on Gorgonilla Island in Columbia, he discovered deformation of the sediment and faults in mud and sandstone that would have been about 2 km deep within the ocean at the time. These contained evidence of prolonged shaking.

When the asteroid hit the Earth, its energy was so great that it sent up molten projectiles — portions of the Earth’s crust that were heated to such a degree that they melted. These pieces eventually resolidified as small glass beads called spherules, and they rained back down to Earth. These spherules eventually settled on the land and in the ocean. The smaller spherules took longer to settle down to the ocean floor. Evidence of shaking was found throughout this layer of spherules, indicating that shaking was persistent for weeks or months.

While earthquakes may be terrifying to live through, they are also a sign of a dynamic and living planet. Understanding where, when, how strong, and how long earthquakes are can help us to better understand why they happen. Perhaps one day, we may even be able to predict them.