Eternal Life: Italian Mosaics of the First Christian Millenium

According to Giorgio Vasari’s Lives, Domenico Ghirlandaio—whose frescoes graced the walls of the Sistine Chapel before those of his apprentice, Michelangelo—once called the art of mosaics as “vera pittura per l’eternita” or “true painting for eternity.” Joachim Poeschke’s Italian Mosaics: 300-1300 demonstrates the seemingly eternal life of these pre-Renaissance mosaics, which contain some of the earliest images of Christian art. In this first published survey of the subject, Poeschke analyzes how religion and politics teamed up to produce these glories of artistry in words while allowing stunning photographs of the mosaics to speak for themselves.

Artists began using small stones called “tesserae” to design images in the third century BCE. Glass tesserae appear in the first century CE. “[M]osaics found their way into church spaces in the fourth century, as the first examples of Christian art on a monumental scale,” Poeschke writes, “and their heyday was over by the fourteenth century, when wall painting almost wholly supplanted them.” Once reserved for tombs and homes, following the example of the ancient Greeks and Romans, mosaics came into their own in churches built by rulers looking to create monuments not only to their god, but also to themselves, as representatives of god’s authority on earth. The mosaic became “the imperial art par excellence,” Poeschke concludes. Constantine the great Christian convert set a standard for patronage and church building projects that later rulers emulated. Mosaics gave life to these trappings of power.

“No medium seemed so capable of capturing the spiritual in material form as mosaic,” Poeschke writes in explanation of how the medium rose to power, “and it was particularly valued by scholars who saw light as the supreme manifestation of beauty and embodiment of the divine.” Light streaming through windows would strike the mosaics, causing the golden ground and rich colors to shine and actually glitter with an unreal, otherworldly beauty. Centuries of alterations to churches have altered the lighting of many mosaics, making it impossible to experience them in the same way the faithful of the first millennium could have. In his immensely useful and comprehensive introduction, Poeschke explains how the power of these mosaics focused the attention of the masses on the apse, the liturgical “heart” of a Christian church. With all eyes on the Mass, mosaics helped define the very nature of Jesus Christ for the illiterate masses through pictures, from the Good Shepherd, to teacher and philosopher, to cosmic creator, to emperor of the otherworldly plane peopled by the saints. This final take set up a neat parallel to the imperial patron, who demanded the same devotion from his subjects as Jesus did from the saints.

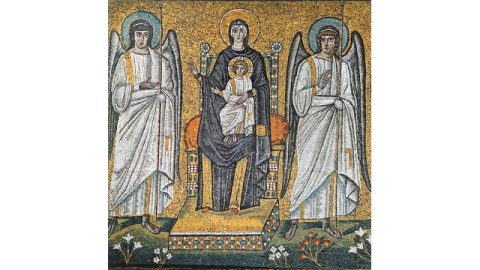

Italian Mosaics: 300-1300 makes you feel as if you are actually there viewing the mosaics, with Poeschke at your side. Poeschke introduces each site and explains the iconography and significance with direct references to the images, which are beautifully rendered both in distant shots to give context as well as in extreme close-ups to show the intricacy of some of the tesserae work. In the Cathedral at Cefalu (circa 1145-1160), Poeschke writes, “The Pantocrator’s expression, one of equanimity and gentleness, remains wholly undisturbed by the virtuosic play of curving lines of tesserae.” The stunning close-up of this representation of Christ gives you a vantage point even the ancient faithful never had. Poeschke points out symbolism that modernity has left long behind. “Mary is seated on a throne richly adorned with precious stones, and like the Child she holds in her lap, she faces the viewer directly,” he writes of Enthroned Madonna and Child between Angels in the Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo of Ravenna, Italy (shown above, circa 500 and 560). “Her purple tunic and palla are adorned with gold stripes and emblems. She has raised her right hand in readiness to speak. …Whereas the Madonna fixes wide-open eyes on the viewer, the Child gazes into the distance, a suggestion of his divinity.” The history of Christianity is literally written on these walls. Poeschke translates this language for the modern viewer to understand and enjoy.

But even if you don’t buy the theology, Italian Mosaics: 300-1300 will give you plenty of eye candy to enjoy. Schematics of the more complex church decorations allow you to make sense of the more intricate wholes, while individual photographs break them down into digestible bits for the soul. Drinking in the still glittering golden grounds and saturated, dark blue skies upon which Christ, Mary, the Apostles, and saints act out the scriptures will make anyone believe in eternal life—at least for the medium of the mosaic.

In a George Lucas-esque way, Poeschke writes Italian Mosaics: 300-1300 as a kind of prequel, specifically to his earlier study, Italian Frescoes: The Age of Giotto. “The Age of Giotto” actually begins at the end of the age of the mosaic. Like his teacher Cimabue, Giotto first worked on a grand scale in mosaics. The fragments of Giotto’s mosaics that exist today give only a glimpse of his influence on the state of the art of mosaics in the late 13th century. Some critics in the 14th and 15th centuries actually considered Giotto’s mosaics to be his most important work. Pietro Cavallini’s mosaics in Santa Maria in Trastevere in Rome, Italy (circa 1296-1300) show the presence of Giotto or at least his style. “It is still uncertain whether it was Cavallini who influenced Giotto or vice versa,” Poeschke admits, but there’s no debate that a new approach to mosaics led directly to a new approach to painting that found its ultimate realization in the Renaissance. In that sense, these mosaics gave birth to Michelangelo and other masters. If we live on through our children, the artistry analyzed by Joachim Poeschke in Italian Mosaics: 300-1300 will truly live for all eternity.

[Image: Enthroned Madonna and Child between Angels. Nave, north wall. Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, Italy. Nave, Circa 500 and 560.]

[Many thanks to Abbeville Press for the image above and for a review copy of Italian Mosaics: 300-1300 by Joachim Poeschke.]