#23: Cut Special Education

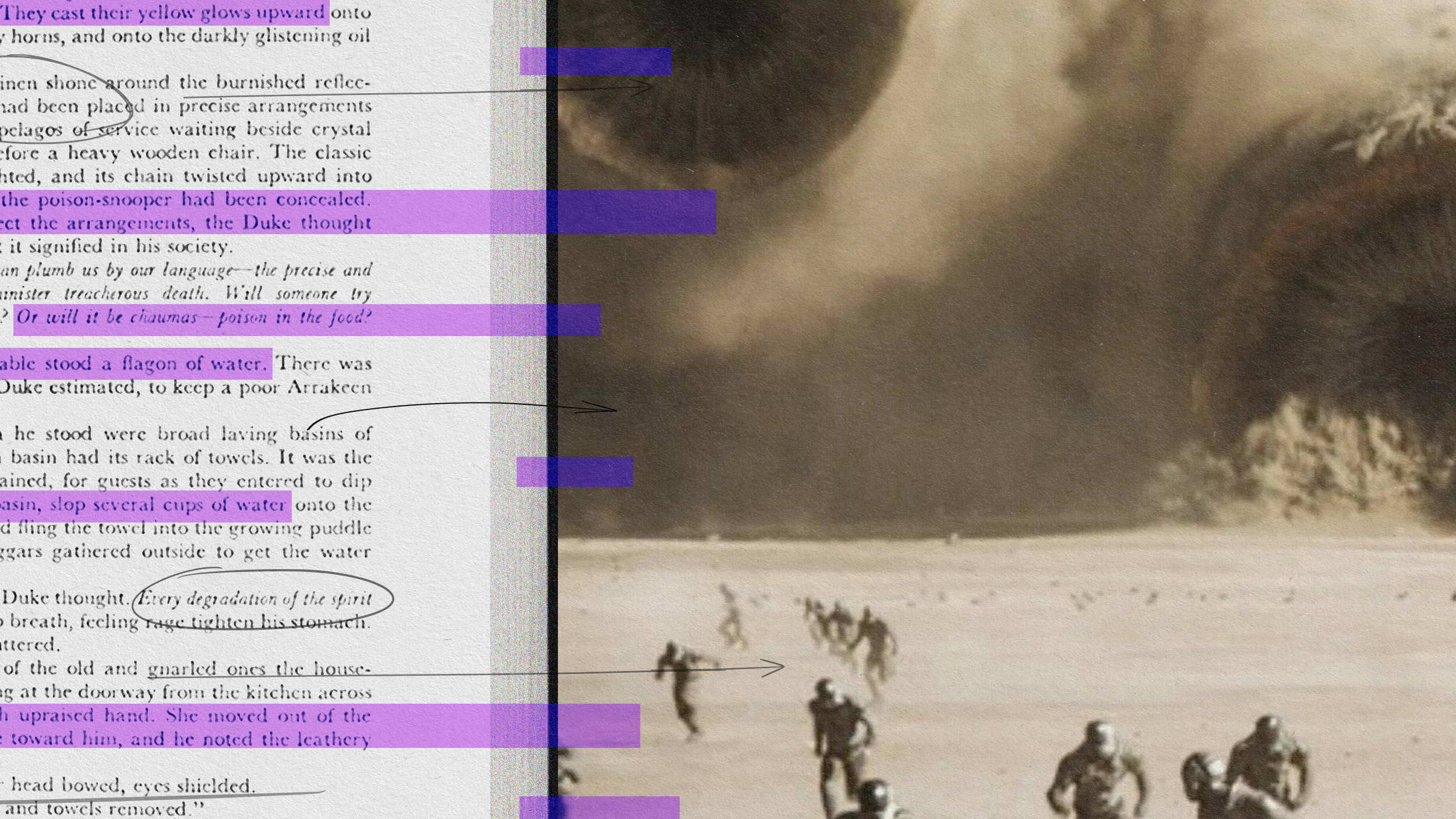

“Is the purpose of public education to nurse students or to teach them?” asks Brian Crosby, a twenty-year veteran high school English teacher and the founder of the American Education Association, in his book Smart Kids, Bad Schools.

Crosby tells Big Think we need to decrease funding for special education and inform the public that these programs waste an inordinate amount of money. He thinks it’s not only bad policy that’s responsible for this overgenerous allocation of resources, but also certain parents who selfishly exploit their children’s disabilities in order to get them ahead.

According to the research of Dr. Jay P. Greene, Senior Fellow at the Manhattan Institute and head of the Department of Education Reform at the University of Arkansas, almost one in seven students in the U.S. is classified as having a disability. This marks a 63% increase in the number of “disabled” children in US public schools since 1976, the year President Ford’s Education for All Handicapped Children Act—now known as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)—granted over one million children previously kept at home or in institutions access to public schools from birth until twenty-two years of age.

“Originally, the federal government was to provide 40 percent of the extra costs associated with educating the disabled children,” Crosby says, “However, as recently as 2002, that participation amounted to only 18%, leaving local and state governments to make up the difference.” In 2004, for instance, Crosby says the government sources provided over $4 billion for California’s 700,000 special ed students, but another $1.6 billion had to be siphoned off the general education budget to make the up difference.

What’s especially odd about this disproportionate allocation of the education budget, according to Greene, is that students today are no more disabled than they were in 1976. Essentially, he believes, there has just been an increase in the number of students who are categorized as disabled. “Almost all the growth in special education over the last three decades has occurred in just two of the thirteen federal categories for disabilities: specific learning disability (SLD, which includes dyslexia), and ‘other health,’ (which includes attention-deficit disorders). The size of the remaining eleven federal categories combined has remained relatively flat, while SLD has tripled and ‘other health’ has quadrupled. Those two categories account for 86 percent of the increase in special-education enrollments,” wrote Dr. Greene in a 2009 National Review Article.

Greene also points out that reported disability rates lack credibility because they vary dramatically from state to state: “In New Jersey, for example, 18 percent of all students are classified as disabled, but in California the rate is only 10.5 percent. There is no medical reason why students in New Jersey should be 71 percent more likely to be placed in special education than students in California.”

Crosby admits that part of this increase is due to schools formally classifying remedial learners—kids who are simply struggling academically—as “disabled” just to receive more funding. But mom and dad have caught on too: “Parents want to get their kids labeled special ed so they can get additional treatment, additional help, and additional time to take their exams,” says Crosby, “I see it with my own eyes; students who are fully capable of taking standardized tests are allotted extra time for their exams even though I know there’s nothing wrong with them. I guess that’s the nature of the beast.”

Takeaway

12% of U.S. public school students are categorized as needing special education services, while 22% of all education funding goes to special education programs. Special education students don’t need twice as much funding as non-special-education students, says Crosby. The needs of a few have far outweighed the needs of the many.

Currently, about 25% of an individual public school’s budget is left to the discretion of its principal. Crosby says if local and state governments gave each public school a higher percentage of their budget to manage as they saw fit, special education students would receive a more equitable allocation of resources. For students who are truly disabled, Crosby says health insurance companies should share the burden of their care.

Why We Should Reject This

“In the 35 years since IDEA was enacted, significant progress has been made toward meeting major national goals for developing and implementing effective programs and services for early intervention, special education and related services,” says Alexa Posny, U.S. Assistant Secretary of Education for the Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services. If special education were cut, it would not only jeopardize the needs of the over 6.6 million children and youth who receive special education and related services to meet their individual needs, but also almost 350,000 infants, toddlers, and their families, who are eligible for early intervention programs and services.

“Ultimately, any funding system should ensure and promote a unified system of education that does whatever it takes for every student to succeed,” says Posny. “I truly believe that access to education is the civil rights issue of our time and so it is appropriate that we celebrate the 35th anniversary of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act this year. The passage of this landmark law ushered in a new spirit of inclusion and hope to our public school classrooms and achieved a founding truth of our nation—that all of our citizens are entitled to the same privileges, pursuits and civil rights.”

More Resources

— “End the Special-Ed Racket,” an article Marcus A. Winters and Jay P. Greene.

— A federal site for information about the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).